Trusted News Since 1995

A service for global professionals · Monday, May 18, 2020 · 517,296,824 Articles · 3+ Million Readers

Trusted News Since 1995

A service for global professionals · Monday, May 18, 2020 · 517,296,824 Articles · 3+ Million Readers

by Aklog Birara (Dr.)

Part II of III

Part II of III

This commentary is the second of a series setting the background on Africa’s foreign debt. In graduate school at the School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) of the Johns Hopkins University where the emphasis was on political economy and regional studies, I used to argue with my distinguished professors that Africa’s abject poverty was a function of untold oppression, suffering, theft and robbery by European colonialism, outright racism and the colonialists’ divisive schemes and institutions that persist to this day.

The policy, structural and institutional hurdles of the transatlantic slave trade that enriched Europeans, North American Whites and Latin American Hispanics and that kept Blacks trapped in a cycle of perpetual poverty remain intact. The ugly face of institutional racism in the United States is now wide open; and has been aggravated by COVID-19. One would have thought rightly that, by this time in the 21st century, African-Americans, Black immigrants, Indians and other Asians and Hispanics who contribute to the richness of American society would no longer face racism and or marginalization.

Africa is home to one of the world’s largest youthful populations. Given a conducive policy and political environment, I am convinced that this human capital has enormous potential to transform Africa’s economy; and to make abject history a story of Africa’s past. Among the requisite transformative ingredients is to shed the outdated development paradigm of development that caters to political elites and to global capital. Africans need to embrace a development model that caters to community, humanity, human worth, equity and sustainability. Africa cannot afford to adhere to the opposite development model.

I remember attending high school in Pennsylvania, college in Indiana and graduate school in Washington D.C, all in the midst of liberal of scholarships from the generous people of the United States, that there were two powerful civil rights movements and ideologies on two sides of the Atlantic: the one led by Dr. Martin Luther King in the USA and the other in Africa championed by Pan-Africanists such as Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere, Patrice Lumumba, Amilcar Cabral and others. Cabral understood best the corrosive and oppressive nature of colonialism, imperialism and racism. He said this: “The colonists usually say that it was they who brought us into history: today we show that this is not so.” I never for once accepted the value-added of the colonialist narrative of “a civilizing mission and role” in Africa or anywhere else. I understood its exploitative nature though.

Major colonial powers that divided Africa among themselves like a piece of merchandise, notably, Belgium, France, Great Britain, Holland, Portugal, Spain and the late comer to the conquest, Fascist Italy and earlier Turkey under the Ottoman empire as well as imperial Japan and Nazi Germany have all participated in massive brutalities, killings, dehumanization and subjugations of hundreds of millions of peoples; and in the exploitation of minerals and other natural resources, in the marginalization of indigenous peoples and their communities most notably in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and other places. These conquerors and colonizers created artificial boundaries in many countries in Africa. They planted the seeds of ethnic and religious divisions that remain hurdles to this day. They inflicted psychological scars that still need healing. They robbed artifacts and took them to their homelands. They deliberately and systematically degraded local and indigenous creativity, innovation and institutions.

In the case of the massive slave trade, there has not been repentance for dehumanization, degradation and for crimes against humanity. Despite huge efforts among African-Americans, the demand for reparation has not come to fruition.

I shall always remember Walter Rodney’s classic book, “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa” in which he says “Many guilty consciences have been created by the slave trade. Europeans know that they carried on the slave trade, and Africans are aware that the trade would have been impossible if certain Africans did not cooperate with slave ships. To ease their guilty consciences, Europeans try to throw the major responsibility for the slave trade on to the Africans. One major author on the slave trade (appropriately titled Sins of Our Fathers) explained how many white people urged him to state that the trade was the responsibility of African chiefs, and that Europeans merely turned up to buy captives- as though without European demand there would have been captives sitting on the beach by the millions! Issues… can be correctly approached only after understanding that Europe became the center of a world-wide system and that it was European capitalism which set slavery and the Atlantic slave trade in motion.” This mindset of blaming the oppressed is preserved and prompted.

The slave trade paved the way for the outright annexations of lands and the exploitation of Africa’s minerals such as gem stones, diamonds, gold, copper, high value industrial commodities that contributed immensely to European, North American other Western country rapid manufacturing and industrialization. Trade relations between Africa and Europe reflected Europe’s dominance and Africa’s dependence, governance that needs overhauling.

“From the beginning, Europe assumed the power to make decisions within the international trading system. An excellent illustration of that is the fact that the so-called international law which governed the conduct of nations on the high seas was nothing else but European law. Africans did not participate in its making, and in many instances, African people were simply the victims, for the law recognized them only as transportable merchandise. …. Above all, European decision-making power was exercised in selecting what Africa should export – in accordance with European needs.” This too needs overhaling.

Things have changed dramatically since then. This is because African nations have alternatives to trade their commodities and to import what they need, for example, from non-traditional sources such as China and India. Despite this alternative that allows African nations to make hard choices, sustainable growth and development in Africa is still weak and uncertainty looms large, especially when unexpected and cataclysmic events such as COVID-19 occur.

If we flip the situation though, COVID-19 offers African nations to ask the hard and inevitable question of whether or it is not time for African nations to translate Pan-Africanism into a concrete set of new narratives and projects that would bring substantial socioeconomic resiliency for Africans as a whole. The Organization of African Unity (the OAU) has already evolved into the next phase of Pan-Africanism, namely, into the African Union (AU) that Nkrumah, Nyerere and Haile Selassie had hoped for. Today, this Pan-African organization acts as the sole representative and collective voice for Africans. If scaled-up, I suggest that the AU will have greater weight, leverage and potential impact in global governance than individual nations. In order to win and to compete, Africa needs to abandon national fragmentation.

As a collective body, the AU can, for example:

These suggestions might sound wishful. It will not be if and when the AU determines to be bold and innovative enough and spearheads transformation that will lead to the formalization of an African Economic Union (AEU) similar to that of the European Union (AU). The AU must recognize by now that scale does matter for Africa’s survival and prosperity.

You may rightfully ask “Why worry about Africa at all?”

Africa is no longer the “Dark Continent” depicted in Tarzan like movies. It is an emerging and dynamic continent with more than 1 billion people. By all accounts, it is a developmental frontier. It has potential to contribute to the global common good in multiple ways.

This emerging African development is now adversely impacted by the pandemic. Africa has to deal with the same and common enemy, the pandemic that afflicts the rest of the globe. As I urged in this commentary, each African nation cannot do it alone. The global economy faces a depression type recession. This affects the entire Africa.

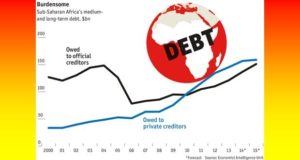

Africa, especially Sub-Saharan Africa, does not possess the monetary and financial resources and the health infrastructural to deal with COVID-19.

Below are four economic variables that affect all African countries:

Remittances support families. Remittances generate foreign exchange and enhance development. Remittances help governments offset foreign exchange shortfalls, etc.

Early statistics from remittances transfer companies from the U.K. to Eastern Africa shows a decline of 80 percent in remittance transfers. Gulf countries have begun to expel migrant workers, thereby compounding the remittance short fall. Experts tend to believe that remitters from rich countries enjoy a safety net that may mitigate losses. This too is debatable. In the U.S. job losses from the pandemic affect more than thirty-six million people with no end in sight.

Estimates of job losses for developing nations emanating from pull back that is driven by the pandemic are in excess of 150 million, the brunt borne by youth.

This huge drag requires bold and life changing interventions. Africa as a whole, and especially Sub-Saharan Africa faces two interrelated problems at the same time.

First thing first though. The possible loss of 4 million lives in SSA from COVID-19 that is estimated by the UK’s famous Imperial College modelers is gruesome. It must be prevented at all cost. Even if all efforts are carried out by governments and the world community, the minimum number of African lives that could be lost as a result of the pandemic is forecast at 800,000. Infections among Ethiopians are estimated at 1.4 million. There is no projection in terms of deaths from COVID-19.

On April 17, 2020, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) reported that “Anywhere between 300,000 and 3.3 million African people could lose their lives as a direct result of COVID-19. Rates projected by Trinity College and by the ECA depend entirely on the timing, efficiency and effectiveness of intervention measures taken to stop the spread the pandemic. The slower the response, the higher the death rate.

Let me summarize this commentary with caution but with a positive note. Africa must concentrate on prevention. In this regard:

Part III of this series will focus on the effects of the Pandemic on the economies of African nations. I shall also propose a set of recommendations for creditors to consider.

Civil Society, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Featured, Global, Global Governance, Headlines, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, Poverty & SDGs, TerraViva United Nations

Maimunah Mohd Sharif is United Nations Under-Secretary-General and Executive Director of UN-Habitat & Leilani Farha is the former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing, and Global Director of The Shift.

The Bijoy Sarani Railway Slum in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Credit: UNHabitat/Kirsten Milhahn

– Public health officials are calling the “stay home” policy the sacrifice of our generation. To flatten the curve of COVID-19 infections, this call of duty is now emblazoned on t-shirts, in street art and a celebrity hashtag.

But for the 1.8 billion people around the world living in homelessness and inadequate shelter, an appeal to “stay home” as an act of public health solidarity, is simply not possible. Such a call serves to highlight stark and long-standing inequalities in the housing market. It underscores that the human right to shelter is a life or death matter.

Throughout this global pandemic, governments are relying on access to adequate housing to slow the viral spread through self-isolating or social distancing policies. Yet, living conditions in poor or inadequate housing actually create a higher risk of infection whether from overcrowding which inhibits physical distancing or a lack of proper sanitation that makes regular hand-washing difficult.

At the most extreme, people experiencing homelessness must choose between sleeping rough or in shelters where physical distancing and adequate personal hygiene are almost impossible. Homeless populations and people living in inadequate housing often already suffer from chronic diseases and underlying conditions that make COVID-19 even more deadly.

It is now clear, housing is both prevention and cure – and a matter of life and death – in the face of COVID-19. Governments must take steps to protect people who are the most vulnerable to the pandemic by providing adequate shelter where it is lacking and ensuring the housed do not become homeless because of the economic consequences of the pandemic.

These crucial measures include stopping all evictions, postponing eviction court proceedings, prohibiting utility shut-offs and ensuring renters and mortgage payers do not accrue insurmountable debt during lockdowns.

In addition, vacant housing and hotel rooms should be allocated to people experiencing homelessness or fleeing domestic violence. Basic health care should be provided to people living in homelessness regardless of citizenship status and cash transfers should be established for people in urgent need.

Steps should be quickly taken to establish emergency handwashing facilities and health care services for at-risk and underserved communities and informal settlements.

In many cities and countries, emergency measures are already moving in this direction.

Berlin opened a hostel to temporarily house up to 200 homeless people, catering to all nationalities. The Welsh government pledged GBP10 million to local councils for emergency homeless housing by block booking empty lodging like hotels and student dormitories.

A woman outside a community run water facility in Old Town, Accra Ghana. Credit: UNHabitat/Kirsten Milhahn

In South Africa where under half of all households have access to basic handwashing facilities and in Kenya, where it is under a quarter of households, governments are increasing access to water for residents living in rural areas and informal settlements by providing water tanks, standpipes, and sanitation services in public spaces.

Many jurisdictions, such as Canada’s province of British Columbia, have suspended evictions. The eviction ban means landlords cannot issue a new notice to end a tenancy for any reason and existing orders will not be enforced.

Spain, France, the United Kingdom and the United States have announced mortgage postponements in an effort to curb potential defaults.

National and local governments are also working with the private sector to tackle housing issues. For example, Singaporean firms with government backing are providing accommodation for Malaysian workers who had been commuting to Singapore daily.

And as they are no tourists in Barcelona, the city has agreed with the Association of Barcelona Tourist Apartments to allocate 200 apartments for emergency housing for vulnerable families, homeless people and those affected by domestic violence.

Some cities are leveraging citizen solidarity. Residents of Los Angeles are making hand-washing stations for homeless people living in a depressed area known as Skid Row which are installed and maintained by a local community centre.

All of these urgent measures and more are desperately needed and demonstrate the way in which housing is inherently connected to our collective public health. These successful interventions also show concrete ways that governments and communities can effectively tackle the pre-existing global housing crisis – a crisis which affected at least 1.8 billion people worldwide, even before the pandemic.

In 2018 the European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless reported that homelessness had skyrocketed across the continent. In the United States, 500,000 people are currently homeless, 40 per cent of whom are unsheltered.

In April last year, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) warned that rent is currently the biggest expense for households accounting on average for one-third of their income. In the last two decades, housing prices have grown three times faster than incomes.

The current global housing system treats housing as a commodity. In times of crisis, the inefficiencies of the market are clear with the public sector expected to absorb liabilities.

This is not sustainable and many cities are struggling to find shelter for their citizens. COVID-19 has brought into sharp relief the housing paradox – in a time when people are in n desperate need for shelter, apartments and houses sit empty. This market aberration needs correcting.

Governments are at a crossroads. They can treat COVID-19 as an acute emergency and address immediate needs without grappling with hard questions and fundamental questions about the global housing system.

Or they can take legislative and policy decisions to address immediate needs, while also addressing the present housing system’s structural inequalities, putting in place long term ‘rights-based’ solutions to address our collective right to adequate shelter. Housing must be affordable, accessible and adequate.

COVID-19 is unlikely to be the last pandemic or global crisis that we face. What we do now will shape the cities we live in, and how resilient we will be in the future.

Civil Society, Featured, Global, Headlines, Health, Human Rights, Humanitarian Emergencies, Inequity, TerraViva United Nations

Abby Maxman is President & CEO of Oxfam America

Credit: Oxfam America

– NGOs, at the international, national – and most of all local – level are on the frontlines every day.

I just heard from Oxfam staff in Bangladesh, that when asked whether they were scared to continue our response with the Rohingya communities in Cox’s Bazar, they replied: “They are now my relatives. I care about them — and this is the time they need us most.’”

These people – and those that they and others are supporting around the globe – are at the heart of this crisis and response.

As we talk about global figures and strategies, we must remember we are talking about parents who must decide whether they should stay home and practice social distancing or go to work to earn and buy food so their children won’t go hungry; women who constitute 70% of the workers in the health and social sector globally; people with disabilities and their carers; those who are already far from home or caught in conflict; people who don’t know what information to believe and follow, as rumours swirl.

Looking more broadly, we see that the COVID-19 crisis is exposing our broken and unprepared system, and it is also testing our values as a global community. COVID-19 is adding new and exacerbating existing threats of conflict, displacement, gender-based violence, climate change, hunger and inequality, and too many are being forced to respond without the proper resources – simple things like clean water, soap, health care and shelter. We must be creative and nimble to adapt our response in this new reality.

Most vulnerable communities

We know too well that when crisis hits, women, gender diverse persons, people with disabilities and their carers, the elderly, the poor, and the displaced suffer the worst impacts as existing gender, racial, economic and political inequalities are exposed.

Abby Maxman

These communities need to be at the center of our response, and we, as the international community, must listen to their needs, concerns and solutions.

Access

As we continue to ramp up our response, we must have access to the communities most in need. Likewise, COVID-19 cannot be used as an excuse to stop those greatest in need from accessing humanitarian aid.

Border closures are squeezing relief supply and procurement chains; Lockdowns and quarantines are blocking relief operations; And travel restrictions for aid workers have been put in place, disrupting their ability to work in emergency response programs.

Authorities should absolutely take precautions to keep communities safe, but we need to work at all levels to also ensure life-saving aid can still get through and people’s rights are upheld.

Local and national NGOs are on the frontline of the COVID-19 response, and communities’ access to the essential services and lifesaving assistance they provide must be protected. We also know that with effective community engagement, we can gain better and more effective access to communities.

Humanitarian NGOs and partners are adapting our approaches to continue vital humanitarian support while fulfilling our obligation to “do no harm.”

This adaptive approach, and our experience of ‘safe programming,’ shifting to remote management where possible; and scaling back some operations where necessary—will all be crucial as COVID-19 restrictions continue to amplify protection concerns and risk of sexual exploitation and abuse.

Funding

To mount an effective response, we must draw on our collective experience, but this crisis also offers an opportunity to change the way we work, including setting up new funding mechanisms to allow our system to leverage the complementary roles we all play in a humanitarian response.

Overall, NGOs urgently need funding that is flexible, adaptive, and aligned with Grand Bargain commitments. Our work is well underway, but more is needed to get resources to the frontlines.

We need to better resource country based pooled funds, which are crucial for national and local NGOs. Now more than ever, donors must support flexible mechanisms to increase funding flows to NGO partners.

Next Steps

In closing, the international community needs to come together to battle this pandemic in an inclusive and a responsive way that puts communities at the heart of solutions. Even while we respond in our own communities, we must see and act beyond borders if we are ever to fully control this pandemic.

The planning and response to COVID-19 need to be directly inclusive of local and national NGOs, women’s rights organizations, and refugee-led organizations leaders. We must address this new threat, while still responding to other pressing needs for a holistic response.

This means continuing our response to the looming hunger crisis, maintaining access to humanitarian aid, and supporting existing services including sexual and reproductive health and gender-based violence services.

We need to ensure humanitarian access is protected to reach the most vulnerable.

And funding needs to be quickly mobilized through multiple channels to reach NGOs and must be flexible both between needs and countries.

This much is clear: We cannot address this crisis for some and not others. We cannot do it alone. The virus can affect anyone but disproportionately affects the most marginalized. It is our collective responsibility to ensure that our global response includes everyone.

We owe it to those dedicated staff and their honorary “relatives” in Cox’s Bazar, and all those like them around the globe, to get this right.

This article was adapted from Abby Maxman’s comments as the NGO representative at the UN’s Launch of the Updated COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan on May 7, 2020.

Asia-Pacific, Civil Society, Featured, Headlines, Health, Poverty & SDGs, TerraViva United Nations

This is an opportunity for civil society to highlight the plight of migrant labourers that existed even before the pandemic.. Picture courtesy: Anand Sinha

– The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has shown us something that most of us haven’t seen in our lifetimes: Large numbers of people unable to have two meals a day.

The tragedy is that the government has enough and more foodgrains to feed people during this time; the real issue is of distribution—both in terms of broken supply chains, as well as the insistence of the government to limit distribution to beneficiaries under the National Food Security Act (NFSA), ie, priority ration card holders. This approach is flawed because the NFSA has many exclusions, with some of the poorest of the poor, nomadic or Adivasi communities, and the urban poor being left out. Moreover, ration cards are of no use to migrant workers stuck outside their home state.

There are similar issues of exclusion in other services as well, such as livelihoods and healthcare. This is where civil society must step in—to put pressure on the government to universalise these services.

We, at the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) and through many networks, have been petitioning the government to distribute foodgrains to everyone, and we need to apply this kind of pressure at a larger scale. We’ve seen this work in the past, in the case of programmes such as NFSA (that focuses on food security) and the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA)—both these were a result of consultative processes between the government and civil society. In fact, these rights-based legislations are providing us with the framework for public service delivery during this crisis, and they need to be effectively enhanced.

Therefore, if the government does not listen, we have to make them listen. I believe the people of this country know how to engage with the government—even when we disagree with our leaders, or they don’t listen to us. We live in a constitutional democracy, and the mantle therefore lies with citizens and civil society organisations to put pressure on the government, and to recreate society on the principles of equality, respect, and solidarity. In the short term, this means that we need to build a national movement to ensure that everyone gets access to food, livelihood, and healthcare.

But how can we do this, given the urgency of the situation and the restrictions that have come with it? What is our role in this massive national exercise to ensure that every citizen of the country has food to eat, quality health services, and livelihood opportunities? I believe there is plenty we can do.

Build a network of civil society

Civil society will have to build a network that cuts across the country. We will need to map the different organisations and groups providing relief in every district, block, and down to every village. We can do this because we have volunteers and workers—from field staff of nonprofits to government school teachers—all over the country, and we know whom we can contact for any information or assistance at any place.

The strength of civil society lies in knowing and being the small, decentralised units that have taken responsibility for their entire area—identifying the number of people in the area, the relief needed, the gaps in government relief, the challenges on the ground, and so on. By bringing them together and forming a network, we can enable these units to call upon each other for assistance, such as procuring material or rebuilding supply chains. Most importantly, the network can have a voice at the national-level that says everyone is entitled to benefits, even if they are not ration card holders or active workers under NREGA.

Stand in solidarity with those delivering essential services

COVID-19 is a high-risk disease, and we need to be very careful; but we cannot simply lock ourselves in our homes, because then those who are most vulnerable will not survive. Essential services absolutely have to continue. We have to build systems and mechanisms for safe delivery of services, and public servants have to be motivated, and given economic and moral support. Even though this has to be primarily done by the government, civil society organisations have a huge role to play as well.

For instance, we need to stand in solidarity with those who are currently delivering these services—frontline health workers, sanitation workers, people running ration shops and kirana stores, those making home deliveries of goods, and so on. We have to understand their problems and put pressure on the government to support them. The Delhi government recently announced insurance of INR 1 crore for frontline workers. That is the kind of security we should demand for every individual delivering services in this period. We have to build a movement around them.

These essential jobs could also be the answer to protecting the livelihoods of the poor during this time, by creating a fallback public works programme, unprecedented in scale. Civil society can demonstrate this model to the government. We need to chart the vital services required today, such as delivering rations and caregiving, and show to the government how people can be employed in these roles. This will not only help communities affected by the pandemic, but the mechanism of doing so might help others in turn.

Continue social movements in innovative ways

We might not be able to organise rallies or protests during the lockdown, but social movements must not stop finding ways to mobilise public opinion. When the lockdown first happened, we filed a case in the Supreme Court to say that all active workers under NREGA should be given wages for all 21 days. The case is being heard via video conferencing. So, we have to explore all options that help put pressure on the government.

We can engage with the state, send press notes, exchange information within our networks of civil society organisations, and document what’s happening on the ground. This way, we can raise issues at the state- and national-level. There are restrictions everywhere, but we cannot stop. We have to be innovative.

Civil society leaders and activists must also continue writing for newspapers and alternative media to highlight the situation of the most vulnerable, and do it in a more organised way, by taking the unheard voices and disseminating them using our networks. These must not just be confined to stories of suffering, but include positive stories and creative practices as well—of people working together despite socio-economic differences. Civil society can also help advocate that best practices in one state be replicated in others.

This is an opportunity for civil society to highlight the plight of migrant labourers that existed even before the pandemic—their work and living conditions, the insecurity of work, and the fact that they have no real social support from the state. We’ve heard people say that they didn’t realise that the migrant workforce is the backbone of our economy. Therefore, in addition to looking after their welfare and security, we must recognise their contribution, and build respect for them and their work—not as a favour, but as a means to empower them.

Many civil society organisations have been working with domestic workers, industrial workers, mine workers, street vendors, or other informal sector workers, but we haven’t managed to get them together and build them into the potent, powerful force that they could be. Perhaps now is the time for us to do that.

This is also an opportunity for civil society to counter the communal narrative that took over the country a few weeks ago. By taking the lead in organising multifaith relief efforts and highlighting positive stories of unity across religious lines, we have to show that the only way to overcome this crisis is by working together. We need to demonstrate compassion and care at this time, and shift the focus of politics to those values.

Work with the government

The role of civil society does not stop at putting pressure on the government. There are many areas that the government is unable to reach; we have to reach there. We have to use our transparency and accountability mechanisms to monitor the government’s work and make sure state resources are well-used. We also need to proactively find the gaps, and help fill those gaps.

The government structure is working well in some areas and not working in others. In some of those places, the government is itself asking for our help. Given the enormity of the intervention required, the government cannot do it on its own, and civil society cannot replace the vast role of the government in facing this crisis. While civil society organisations can take responsibility for one area and fully ensure the well-being of the people there, we must also work with local governments, help people access relief measures down to every rural and urban ward, and fill the gaps in the government’s response. Panchayats and local self-governments also have a very big role to play in this effort.

Apart from this, each one of us needs to think hard of the ways in which we can contribute. As individuals, we can immediately start looking at those around us—in our villages and our localities. Some of us can provide economic resources to plug the government’s gaps; others can take up the job of distribution. Individuals can also devote their time and join campaigns. There needs to be a concerted campaign for instance, to use the excessive foodgrain stocks to universalise the PDS, at least for the next few months. We also need to support the demand for an enhanced employment guarantee programme for rural and urban areas. We don’t realise how powerful the middle-class, English-speaking elite in India is; if they raise their voice enough, we will see improved situations around us.

And lastly, let us not forget democracy at this time—the right to speak, the right to challenge, the right to argue—because today, the only thing millions of poor people have is a voice. We need to amplify that voice to ensure that the most vulnerable get the most support, and those who are affluent only get something if it helps the most vulnerable. How much attention we pay to the millions who have been worst affected by COVID-19 and the lockdown will determine whether or not we come out of this crisis.

The article is based on Nikhil’s online discussion with the team members of Azim Premji Philanthropic Initiatives, Azim Premji University, and Azim Premji Foundation.

Nikhil Dey was one of the founding members of the Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS).

This story was originally published by India Development Review (IDR)

Civil Society, Economy & Trade, Featured, Global, Headlines, Health, Human Rights, Humanitarian Emergencies, Inequity, Religion, TerraViva United Nations

Dr. Azza Karam is the Secretary General of Religions for Peace International and Professor of Religion and Development at the Vrije Universiteit (VU), Amsterdam; Dr. Mustafa Y. Ali is the Secretary General of the Global Network of Religions for Children (GNRC) based in Nairobi, Kenya.

Credit: United Nations

– COVID-19 has spread to many nations around the world, and has been declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization. In the global south, the COVID-19 pandemic has stretched the available medical and health resources, triggered economic shocks, and caused social upheavals and insecurity in many countries and localities.

While the pandemic has caused huge numbers of infections and deaths in the global north, the consequences in the poorer nations in the global south is acute.

Serious challenges arising from responses from authorities to contain the pandemic ranging from hard to soft lockdowns, curfews, limitations in movements, and social distancing, are causing strains in communities.

From fragile economies to ill- equipped health facilities and underfunded health programs, to the almost non-existent social security measures that would ordinarily cushion large segments of pupations from falling further into poverty, the impact on many communities in the global south will be grave.

While COVID-19 has not had a devastating impact on Africa as it has elsewhere, according to official statistics, we fear that this may change.

On the health side, health experts are already warning that the pandemic could yet exact a much heavier death toll in the region if it overwhelms local health services – as has happened in the United States and United Kingdom.

There are also concerns that the relatively weak health systems and patchy testing may be enabling COVID-19 to spread through Sub-Saharan Africa, without a means of registering any of this data.

The official figures to date locate much of the pandemic’s regional burden in places like South Africa, which has reported nearly 5,000 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and recently deployed hundreds of Cuban doctors to help fight its impact, and more than 1,800 confirmed cases in Cameroon, which has launched nationwide testing in April.

Two countries in the region, Lesotho and Comoros, have yet to officially report any cases, let alone Covid related deaths. According to a director of the African Center for Disease Control, the collapse of global cooperation has marginalised Africa in the diagnostics market, and its lack of hospitals combined with a high prevalence of HIV, tuberculosis, malaria and malnutrition could lead to relatively high COVID-19 mortality rates.

Food security is another major issue. Speaking of concerns in Nigeria, Sister Agatha Chikelue, Executive Director of the Cardinal Onaiyekan Foundation and Coordinator of Religious for Peace’s interfaith Women’s Network, noted that people are afraid of dying of “Hovid” – the hunger caused as a result of loss of livelihoods from the lockdown.

Religious leaders join COVID-19 fight in Africa. Credit: United Nations

Small wonder, therefore, that Nigeria is one of the countries already struggling to consider reopening some of their businesses, in spite of dire warnings.

According to a UN report, Africa is home to more than half of the 135 million who suffer acutely from food insecurity, which means there are serious concerns about famines and the potential for a significant death toll.

In other words, we are speaking of very real fears that the Covid crises may cause famine in combination with the drought, which will have dire consequences on the conflict-affected countries in the continent.

John Letzing, Digital Editor of Strategic Intelligence at the World Economic Forum, lists some of the dynamics facing the continent as reported on by a number of different sources. Notably,

Some Africans may be suffering indirectly from the impact of COVID-19 while

abroad – in early April, images and video emerged of Africans in Guangzhou,

China, being subjected to passport seizures and arbitrary quarantine,

according to this report. (The Diplomat). Africa has undergone an incredible

journey to make routine immunization possible, though immunization

coverage in sub-Saharan Africa has stalled at 72%. Now, COVID-19 presents

a further threat to progress, according to this analysis. (New African)

Despite the heralding of the coronavirus, there are those who argue that Africa’s governments did little to prepare themselves, their systems, or their people. Other commentators note that many countries have made plans to ease coronavirus-related measures.

There is some speculation that lessons learned from incidents like the 2014 Ebola outbreak will contribute to some countries’ capacities to weather the storm.

The fact is, that one of the key containment measures—social distancing—will be impossible in the crowded markets, high-density informal settlements and dwellings shared by more than one family. Another oft repeated advise is that of frequent handwashing in clean water. But what happens when clean water to drink, is in very short supply for many households across the sub-Saharan African continent?

Moreover, it is inconceivable that governments will, on their own, be able to meet the needs of all their citizens in this COVID pandemic. Many were already struggling to do so even before the pandemic struck.

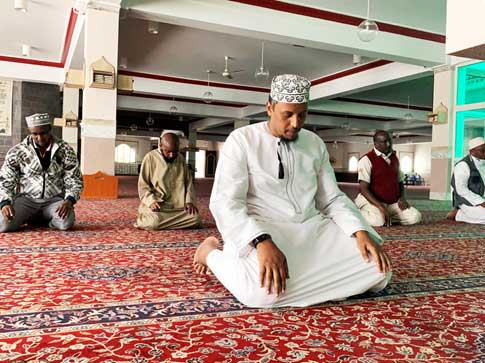

Besides offering spiritual guidance and support, which is increasingly needed in times of fear and uncertainty, faith communities and organizations in Africa as elsewhere, have, over the years, supplemented governments’ efforts to provide education, health, nutritional and other developmental needs to their communities.

They also have been in the forefront of peacebuilding initiatives, and in advocating for rights-based approaches to development, protection of, and ending violence against children and minorities.

With the COVID-19 pandemic ravaging communities and creating fear and despondency, faith-based and faith-inspired organizations are already providing and augmenting critical services in health care provision – including but not limited to palliative care – and as part of the supply chains (for food, medicines, spiritual relief) reaching the heart of communities.

Religious organisations are also key to disseminating accurate news about the impacts and effects of the pandemic, rendering more critical their services as communicators and advisers on behavioral changes needed to keep communities safe.

Those of us engaged in working with religious actors speak of 84% of the world’s people claiming an affiliation to a faith tradition. This applies to all the world, and the sub-Saharan African subcontinent is no stranger to religiosity and belief as normal in everyday lives.

In times of fear, most believers will turn to faith, and this means that religious institutions, religious leaders and religious NGOs are playing a key role including psycho-social healing of COVID-19 traumas.

The fact is, however, that not all faith actors play the same role. And even when most play a positive role in helping communities and governments to cope, this does not mean all do. We know that some faith leaders are adamant that congregating for religious worship is a means of healing, because “God will spare us”.

These messages are hardly helpful when science and life and death experience indicate that social distancing is not only advisable, but downright necessary.

While the UN Secretary General’s call for a global ceasefire to all conflicts has been echoed by many religious leaders around the world, the question remains whether actors involved in extremist groups using religion as their raison d’etre will contemplate heeding such calls.

In fact, COVID-19 lockdowns may even be opportunities to ramp up violence, as government security services are otherwise engaged. This begs two important questions we have yet to find answers for:

To what extent will those religious institutions involved in providing for the daily spiritual, psycho-social, humanitarian care for their communities, and already overwhelmed in reconfiguring the very nature of religious worship, find the wherewithal to engage with the ‘radical fringes’ in African contexts already deeply divided by conflicts?

And what impact will COVID-19 have on the very same armed groups still insistent on playing out their conflicts? Already, some of those who still carry weapons, are working to serve some of their community needs – providing food, water and even money to households having to do without.

And as they serve their communities’ needs, the extremist groups have also ramped up attacks. In March and April, armed attacks in sub-Saharan Africa increased by 37 %, adding significant strain on the already overstrained resources, currently re-directed to COVID-related emergencies.

Sheikh Ibrahim Lethome, Secretary General of the Center for Sustainable Conflict Resolution, and Convener for the GNRC (Global Network of Religions for Children) Horn of Africa Working Group on religious-based extremism, is not surprised that the extremist groups have fully seized the confusion and despondency that COVID-19 has thrust into already fragile communities.

These stretch from the Sahel in West Africa, the Horn of Africa to Southern Africa’s Cabo Delgado in Mozambique

Will COVID-19 offer an opportunity for a different trajectory for some of those groups? As these groups continue to plant bombs, kill and maim, what will become of armed insurgency in the name of religion, when COVID-19 hits hard in Africa?