Introduction

The disease, now caused by a novel coronavirus called severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2, was first identified in the outbreak of the respiratory disease in Wuhan, China.1 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) raises ongoing and serious public health concerns around the world. As of 07th February 2022, the ongoing global pandemic outbreak of COVID-19 has spread to at least 225 countries and territories causing 410,837,662 cases and 5,829,542 deaths (case fatality rate (CFR) = 1.42%) globally.2 The United States of America (USA) reported the highest number of cases (79,293,924) (3, 4) and 942,944 deaths3–7 with a CFR of 1.18%, followed by India (42,631,421) cases and 508,665 deaths with a CFR of 1.19%.3,4,7–10 The first case of coronavirus in Africa was reported in Egypt on February 14, 2020.11,12 By the end of October 2021, 47 African countries were affected, with over 150,000 deaths and over 6.07 million confirmed cases.13 Africa is considered one of the most vulnerable continents due to its strong trade relations with China and poor health care system.4,14,15 As of 07th February 2022, the ongoing global pandemic outbreak of COVID-19 has spread to at least 58 African countries,14,16 including South Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, Ethiopia, and, Libya, and resulted in approximately 6,632,037 cases of COVID-19 and 151,537 deaths only on these five Africa countries.2 In South Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, Ethiopia and, Libya, COVID-19 infections 3,623,962, 1,147,243, 944,175, 466,539, and 450,118 and deaths reached 95,835, 15,593, 26,679, 7363, and 6067, with case fatality rate (CFR) of nearly 0.15%, 0.042%, 0.22%, 0.006%, and 0.086%, respectively.2 This disease has left a permanently dark mark on the history of the human race.12 The coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic will be infamously recorded in history forever.12

In the case of the Southern African countries, the basic reproduction number (R0) for South Africa was estimated to be 7.02.17 This was followed by Zambia with R0 = 2.59 and Namibia with R0 = 2.37.17 The reproduction number for Malawi was 2.16.17 Among the Central African countries considered, Cameroon had an R0 of 3.74, Chad (2.03),17 Gabon (2.37),17 and the Republic of the Congo (2.54).17 Of these countries, Cameroon was the first to be infected with COVID-19, followed by the Republic of the Congo, Gabon, and Chad. Among the African island nations,18 Madagascar (4.97) and Mauritius (9.66) showed the highest breeding numbers.17 In North Africa, Morocco (3.92) is estimated to have the highest basic reproduction number, followed by Tunisia (3.87), Algeria (3.31), and Egypt (2.72).13,17 Similar results were obtained in East African countries. Sudan has the lowest reproduction number (1.98), followed by Ethiopia (2.55), Kenya (3.77), and Rwanda (4.04).17 In addition to this, a new type of COVID-19 emerged in the world.19–21 The virus is constantly changing, which can lead to the emergence of new variants or strains of the virus.19,22 Variants usually do not affect the behavior of the virus. But sometimes they make it work differently.23–25 Omicron variants spread more easily than the original virus that causes COVID-19 and delta variants.17,19,20 The Omicron COVID19 variant was first reported in South Africa on November 24, 2021 (26). It is quickly spreading across the world.20,21,26 The severity associated with Omicron is still unknown, but early reports suggest a mild illness, at least in the younger population.19–21 Individuals infected with the Omicron variant may show symptoms similar to those of previous variants. The presence and severity of symptoms can be affected by COVID19 vaccination status, the presence of other conditions, age, and previous history of infection.20,22,27

The biggest burden of COVID19 depends on the medical system and on the prompt and timely response to the pandemic.27–33 But the problem is that almost all African countries respond slightly too slowly, and some of them cannot use their vaccines effectively.34–36 A series of critical factors can lead to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, some of these factors do not seem to be well understood.17,37 Infectious disease modeling is a powerful tool for infectious disease control that helps to accurately predict characteristics and understand infectious disease dynamics.38–40 In infectious disease models, the incidence rate plays a vital role in the transmission of infectious diseases.38–40 From an epidemiological point of view, the number of people infected per unit time is called the incidence.38–40 Here we consider the incidence of non-linearity, as the number of effective contacts between infectious and susceptible individuals can be saturated by the accumulation of high levels of infectious individuals.38–40 This model is also used to calibrate and predict the number of COVID-19 case data in five high-burden African countries, including South Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, Ethiopia, and Libya, to estimate the model parameters. We assessed the impact of year structure on the dynamics of COVID-19 cases in all five high-burden African countries. The study performed an intervention analysis to identify the essential intervention that could support policymakers in controlling the COVID-19 outbreak in the five high-burden African countries. The model findings can be also helpful to many other countries which are dealing with the critical outbreak of COVID-19 and predict what will happen in the future. The COVID19 pandemic continues to spread in uncertain ways around the world, despite vaccines being available. Due to the uncertainty of the pandemic, it is necessary to properly understand the development of the disease in the community. More research is needed to adequately understand the transmission dynamics of the virus and its variants in Africa. In this study, researchers used a SIMCR model to estimate the basic reproduction number of COVID-19 among five high-burden African countries based on the number of susceptible, infected, mild severe, and series critical severe. The prediction results and the incidence rate estimation could be used by public health officers to plan, and map out strategies to prevent COVID-19 adequately in Africa.

Methods

Study Setting

The study was conducted among five COVID-19 high burdened African countries. These are South Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, Ethiopia, and Libya.

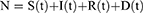

Our study is deterministic modeling where the population is partitioned into five components based on the epidemiological state of the individuals. The model structure that we selected is based on the nature of COVID-19 and general model assumptions to make it simple. In this model, the population is partitioned into five compartments or classes namely: Susceptible S(t), infected I(t), mildly infected population M(t), critical infected population C(t), and recovered R(t) compartments (Figure 1).41 According to this model, a susceptible individual in contact with an infected person is prone to get infected.41–44

|

Figure 1 Flow chart of the SLMCR mathematical model showing the five states and the transitions in and out of each state. |

The flow chart of the SLMCR mathematical model shows the five states and the transitions in and out of each state. S: susceptible population; I: Infected population; M: mildly infected population (moderate symptom); C: critical infected population (critical case); R: recovered population; Λ: recovered rate, λ: infected rate; μ: death rate; β: Recovery rate from M to R; ω: progression rate from latent to a mild compartment; ω2: progression rate from the latent critical compartment; α: the force of saturation infection; γ: recovery rate from mild compartment to recover compartment; β: recovery rate from critical compartment to recovery compartment; ϕ: the rate of progression from mild to critical compartment due to comorbidities with other diseases (Table 1).41

|

Table 1 The Assumed and Fitted Values of Model Parameters for Five High-Burden African Countries |

Ordinary Differential Equations (ODE)

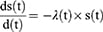

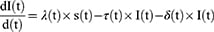

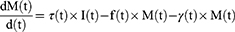

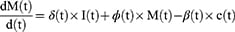

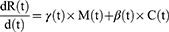

ODEs describe the rate of change in the number of the susceptible, latent, acute, carrier, and recovered compartments at time t.41

These equations are written as follows:

The SICMR model is a compartmental model describing how a COVID-19 disease spreads among the population. The subjects of the SICMR model are susceptible, infected, mild, critical series serious critical, and recovered cases.41

In the model, natural birth rate and natural death rates are considered equal. We use the following symbols to mark the number of individuals in each compartment:41

- S(t): susceptible, representing the number of individuals who do not have COVID-19 diseases at time t but are likely to have COVID-19 disease in the future

- I(t): infected, representing the number of individuals who get COVID-19 disease at time t

- R(t): recovered, representing the cumulative or total number of the recovered groups at time t

- C(t): serious critical infected population, representing the cumulative or total number of patient who has critical symptoms at the time of t

- M(t): mild severe, representing the cumulative or total number of patient who has mild symptoms at the time of t

Results and Discussion

The output below shows the number of people in each compartment. It was modeled for 30 years. As it is shown, the total populations for every five compartments are estimated for each year (Table 2).

|

Table 2 The Number of Populations in Each Compartment of the COVID-19 Model Structure Modeled for 30 Years, South Africa, February 2022 |

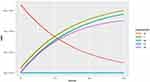

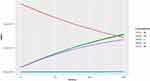

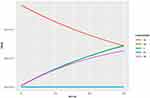

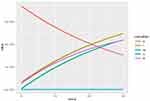

This section estimated the model parameters based on the available five African countries’ COVID-19 reported case data from http://worldometers.info.2 The figures (Figures 2–6) present the pattern of infected individuals, susceptible, mild severe, critical mild severe, and recovered individuals for the next 30 years if the number of infected individuals follows this trend in South Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, Ethiopia, and Libya.

|

Figure 2 The number of populations in each compartment of the COVID-19 model structure modeled for 30 years, South Africa, February 2022. |

|

Figure 3 The number of populations in each compartment of the COVID-19 model structure modeled for 30 years, Morocco, February 2022. |

|

Figure 4 The number of populations in each compartment of the COVID-19 model structure modeled for 30 years, Tunisia, February 2022. |

|

Figure 5 The number of populations in each compartment of the COVID-19 model structure modeled for 30 years, Ethiopia, February 2022. |

|

Figure 6 The number of populations in each compartment of the COVID-19 model structure modeled for 30 years, Libya, February 2022. |

To parameterize the model, we obtained some of the parameter values from the literature (Table 2). Others were fitted or estimated from the data. The model was fitted using R version 4.0.5 using starting points from the data (South Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, Ethiopia, and, Libya, COVID-19 infections 3,623,962, 1,146,041, 940,223, 466,455, and 445,876 and deaths reached 95,817, 15,593, 26,679, 7363, and 6067 respectively).2

The prediction results from the model are also shown in the figure below to show direction and to understand the importance of intervention in the evidence-based decision-making process. The predicted result shows that if the number of infected individuals, number of recovered, and critical series severe follow this trend for the next year, there will be around 6,932,672 in South Africa, 1,568,144 in Morocco, 1,770,862 in Tunisia, 929,366 in Ethiopia, and 853,195 in Libya patients infected. In addition to this, if this trend continues in the next 10 years, there will be around 29,221,559 in South Africa, 5,144,339 in Morocco, 5,925,190 in Tunisia, 5,002,988 in Ethiopia, and 3,545,001 in Libya recovered from COVID-19 by April 30th, 2032, as shown in tables and figures below. This is consistent with the report of WHO, which stated that the number of newly confirmed cases was higher among African countries.42 The pattern of increasing cases is driven by South Africa and Ethiopia, which continue to report the highest numbers of new cases.42

If this trend continues for the next 3 decades, the number of susceptible individuals will decrease, but the number of infected, mild severe patients and recovered individuals will increase. The number of susceptible individuals decreased by 50,732,068 in South Africa, 11,782,920 in Morocco, 10,876,563 in Tunisia, 13,482,005 in Ethiopia, and 6,007,478 in Libya in the next 3 decades.

The following are the ggplots of the above table (Table 2). As those graphs clearly show, the number of susceptible individuals decreased among five high-burden African countries. But the number of infected, mild severe, critical severe, and recovered populations will increase at the end of the studying years. The population in the three compartments will increase over the next 30 years. The population in the critical severe compartment will remain almost constant throughout the study period (Figures 2–6).

Intervention Implementation

Providing COVID-19 vaccine to the population of five high-burden African countries is 70–95% effective to prevent COVID-19 transmission from individual to individual.

Now we can think of the COVID-19 vaccine as an intervention to reduce coronavirus transmission from person to person. Currently, the distribution of vaccines is being offered in all African countries. We want to plan the intervention, by assuming that it is possible to offer the COVID-19 vaccine to half of the population in five high-burden African countries. The model formulation considering the intervention is done as follows.

Let the intervention to be offered is labeled as: “CD_ COVID-19”

Coverage of COVID-19 vaccine (C_ CD_ COVID-19) =0.5(50%),

Efficacy of COVID-19 vaccine (E_ CD_ COVID-19) = 0.76(76%)

Lambda intervention for South Africa=lambda*(1- (C_ CD_ COVID-19 * E_ CD_ COVID-19))

The value of the force of infection (lambda) after intervention will be:

Lambda intervention=lambda*(1- (C_ CD_ COVID-19 * E_ CD_ COVID-19))

Lambda intervention=0.64*(1-(0.5*0.76))

Lambda intervention=0.64*(1–0.38)

=0.64*0.62

=0.3968

Therefore, the intervention will reduce the force of infection by 62%.

Lambda intervention for Morocco =lambda*(1- (C_ CD_ COVID-19 * E_ CD_ COVID-19))

The value of the force of infection (lambda) after intervention will be:

Lambda intervention=lambda*(1- (C_ CD_ COVID-19 * E_ CD_ COVID-19))

Lambda intervention=0.03*(1-(0.5*0.76))

Lambda intervention=0.05*(1–0.38)

=0.03*0.62

=0.0186

Therefore, the intervention will reduce the force of infection by 62%.

Lambda intervention for Tunisia =lambda*(1- (C_ CD_ COVID-19 * E_ CD_ COVID-19))

The value of the force of infection (lambda) after intervention will be:

Lambda intervention=lambda*(1- (C_ CD_ COVID-19 * E_ CD_ COVID-19))

Lambda intervention=0.85*(1-(0.5*0.76))

Lambda intervention=0.85*(1–0.38)

=0.85*0.62

=0.527

Therefore, the intervention will reduce the force of infection by 62%.

Lambda intervention for Ethiopia =lambda*(1- (C_ CD_ COVID-19 * E_ CD_ COVID-19))

The value of the force of infection (lambda) after intervention will be:

Lambda intervention=lambda*(1- (C_ CD_ COVID-19 * E_ CD_ COVID-19))

Lambda intervention=0.004*(1-(0.5*0.76))

Lambda intervention=0.05*(1–0.38)

=0.004*0.62

=0.00248

Therefore, the intervention will reduce the force of infection by 62%.

Lambda intervention for Libya =lambda*(1- (C_ CD_ COVID-19 * E_ CD_ COVID-19))

The value of the force of infection (lambda) after intervention will be:

Lambda intervention=lambda*(1- (C_ CD_ COVID-19 * E_ CD_ COVID-19))

Lambda intervention=0.068*(1-(0.5*0.76))

Lambda intervention=0.068*(1–0.38)

=0.068*0.62

=0.04216

Therefore, the intervention will reduce the force of infection by 62%.

The prediction results after intervention are shown in Table 3. If 50% of the population is vaccinated and if the number of infected individuals, recovers, and critical severe follow the same trend for the next 10 years, it is possible to reduce the number of infected individuals in Africa. There will be around 9,847,641 in South Africa, 15,183,777 in Morocco, 3,773,632 in Tunisia, 2,255,118 in Ethiopia, and 1,893,279 in Libya infected. In addition to this, if this trend continues in the next 10 years, there will be around 9,158,288 in South Africa, 14,268,506 in Morocco, 3,525,578 in Tunisia, 2,117,100 in Ethiopia, and 1,399,768 in Libya recovered from COVID-19 by April 30th, 2032 as shown in figures and tables below. A similar study reported that COV2.S given two months after the initial immunization increased vaccine effectiveness in the short term to 100% against severe disease.45 The previous study has also found that vaccination is an important protective factor against COVID-19.46–55

|

Table 3 The Number of Populations After Intervention in Each Compartment of the COVID-19 Model Structure Modeled for 30 Years, February 2022 |

If this trend continues for the next 3 decades the number of susceptible individuals will increase but the number of infected, mild severe patients, and recovered individuals will decrease. The number of the susceptible individual increased by 30,711,930 in South Africa, 5,919,837 in Morocco, 3,485,020 in Tunisia, 7,833,642 in Ethiopia, and 2,145,404 in Libya in the next 3 decades with compare to the unvaccinated population and the number of infected individuals decreases by 30,479,271 in South Africa, 19,809,751 in Morocco, 3,456,406 in Tunisia, 7,761,993 in Ethiopia and 2,125,038 in Libya.

The following are the ggplots of the above table result after intervention (Table 3). As those graphs (Figures 7–11) clearly show, the number of susceptible individuals decreased among five high-burden African countries. But compared to the previous result (before intervention) the number of susceptible increased and the intervention reduced the number of infected individuals throughout the study period. From the figure, the number of Infected, Mild severe, critical severe, and recovered populations will increase at the end of the studying years. But compared to the previous results (before intervention) there is a dramatic decrease in the number of infected individuals.

|

Figure 7 The number of populations in each compartment of the COVID-19 modeled for 30 years after the intervention, South Africa, February 2022. |

|

Figure 8 The number of populations in each compartment of the COVID-19 modeled for 30 years after the intervention, Morocco, February 2022. |

|

Figure 9 The number of populations in each compartment of the COVID-19 modeled for 30 years after the intervention, Tunisia, February 2022. |

|

Figure 10 The number of populations in each compartment of the COVID-19 modeled for 30 years after the intervention, Ethiopia, February 2022. |

|

Figure 11 The number of populations in each compartment of the COVID-19 modeled for 30 years after the intervention, Libya, February 2022. |

The incidence rates of symptoms and diseases in the general population are important indicators of a population’s health status. The incidence of the COVID-19 pandemic is shown below for the next 30 years among five high-burden African countries. The incidence in the first year will be 55 cases per 1000 in South Africa, 984 cases per 10,000 population in Morocco, 1216 cases per 1000 population, 769 cases per 100,000 population in Ethiopia, and 1097 cases per 10,000 population during one year at risk before intervention. The incidence rate of the COVID-19 pandemic will then decrease till the end of the next 30 years in all countries. But if 50% of the population is vaccinated, the incidence rate in those countries decreases dramatically compared to the unvaccinated population. The Incidence rate after the intervention is 3652 cases per 100,000 in South Africa, 2076 cases per 1,000,000 population in Morocco, 4915 cases per 100,000 population, 3 cases per 1000 population in Ethiopia, and 4385 cases per 100,000 population during one year at risk (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Incidence Rate per 1000 Population Before Intervention and After the Intervention, February 2022 |

Conclusion

SIRD and SIRS models are classical and effective stochastic models of infectious diseases. In this research, the SIMCR model is used to describe the transmission of COVID-19 among five high-burden African countries. South Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, Ethiopia, and Libya are the top 5 COVID-19 high-burden African countries. Through the analysis of the recent data, the number of infected individuals has increased today. If this trend is continuous for the next 30 years we will have around 86 million infected individuals and millions of deaths only in those five African countries. Also, the incidence rates of those countries are high before intervention compared to after intervention. To reduce those problems, vaccination is the best and most effective mechanism. So, vaccinating half of the population in those countries helps to control and reduce the transmission rate of COVID-19 in Africa for the next 30 years. This will lead to preventing 17,212,405 people from becoming infected and millions of deaths being reduced in those five high-burden African countries for the next 30 years. Finally, we hope that the governments will impose the strictest, most scientifically effective containment measures to quickly conquer COVID-19.

Many research works have been done for short terms forecasting periods like 25, 30, and 60 days. Where in this study, the authors took data for the last year and predicted the scenario for the next 30 years. Moreover, the SIRD model showed excellent accuracy in the prediction force of infection and the best intervention method which previous models could not achieve.

So, this model should be applied for forecasting future analysis and identifying the force of infection for any dataset. The limitation that was observed during prediction was that SIRD models upturn the number of susceptible, infected, recovered, and deaths. But SIRD model is the greatest and most effective model to identify the best intervention method and force of infection. In the future, investigators can explore some predictive models such as the ARIMA model and Bayesian networks in COVID-19. This model is also recommended to be applicable for future pandemics and to identify the most effective intervention method.

Ethics Approval

The study was based on aggregated COVID-19 surveillance data in South Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, Ethiopia, and, Libya taken from the worldometer. No confidential information was included because analyses were performed at the aggregate level. Therefore, no ethical approval is required.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available on the following website: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge worldometers for their valuable work.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. CDC. Novel Coronavirus, Wuhan, China. CDC; 2019. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/index.html. Accessed August 23, 2022.

2. Worldometer. Coronavirus Cases and Deaths. Delaware, USA: Dover; 2020.

3. Namazi H, Krejcar O, Subasi A. Complexity and information-based analysis of the variations of the SARS-CoV-2 genome in the United States of America (USA). Fractals. 2020;28(07):2150023. doi:10.1142/S0218348X21500237

4. Rahman A, Kuddus MA. Kuddus MAM the transmission dynamics of C-19 in six high-burden countries. Modelling the transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in six high-burden countries. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:1–17. doi:10.1155/2021/5089184

5. Tsang CA, Tabnak F, Vugia DJ, Benedict K, Chiller T, Park BJ. Increase in reported coccidioidomycosis—United States, 1998–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(12):217.

6. Bialek S, Bowen V, Chow N, et al.; Covid CDC, Team R. Geographic differences in COVID-19 cases, deaths, and incidence—United States, February 12–April 7, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(15):465. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e4

7. Suresh R, James J, RSJ B. Migrant workers at crossroads–The COVID-19 pandemic and the migrant experience in India. Soc Work Public Health. 2020;35(7):633–643. doi:10.1080/19371918.2020.1808552

8. Pai C, Bhaskar A, Rawoot V. Investigating the dynamics of COVID-19 pandemic in India under lockdown. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;138:109988. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109988

9. Singh AK, Misra A. Impact of COVID-19 and comorbidities on health and economics: focus on developing countries and India. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14(6):1625–1630. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.08.032

10. Ghosh A, Nundy S, Mallick TK. How India is dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic. Sensors Int. 2020;1:100021. doi:10.1016/j.sintl.2020.100021

11. Gilbert M, Pullano G, Pinotti F, et al. Preparedness and vulnerability of African countries against importations of COVID-19: a modeling study. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):871–877. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30411-6

12. World Health Organization. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. World Health Organization; 2021. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 10 July, 2021.

13. World Health Organization. African W. Coronavirus (COVID-19): WHO African Region numbers at a glance; 2021.

14. Tull DM. China’s engagement in Africa: scope, significance, and consequences. J Mod Afr Stud. 2006;44(3):459–479. doi:10.1017/S0022278X06001856

15. George G, Corbishley C, Khayesi JNO, Haas MR, Tihanyi L. Bringing Africa i: promising directions for management research. Acad Manag Ann. 2016;59:377–393. doi:10.5465/amj.2016.4002

16. Dzinamarira T, Dzobo M, Chitungo I. COVID‐19: a perspective on Africa’s capacity and response. J Med Virol. 2020;92(11):2465–2472. doi:10.1002/jmv.26159

17. Iyaniwura SA, Rabiu M, David JF, Kong JD. The basic reproduction number of COVID-19 across Africa. PLoS One. 2022;17(2):e0264455. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0264455

18. GARDAWORLD. Ghana: authorities impose a lockdown on two regions due to COVID-19 from March 30; 2021.

19. World Health Organization. Update on omicron; 2021. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/28-11-2021-update-on-omicron. Accessed November 30, 2021.

20. Karim SSA, Karim QA. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: a new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398(10317):2126–2128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02758-6

21. Gerli AG, Centanni S, Soriano JB, Ancochea J. Forecasting COVID-19 infection trends and new hospital admissions in England due to SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern Omicron. medRxiv. 2021.

22. Morse SS. Factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Plagues Polit. 2001;8–26. doi:10.1101/2021.12.29.21268521.

23. Luria SE, Delbrück M. Mutations of bacteria from virus sensitivity to virus resistance. Genetics. 1943;28(6):491. doi:10.1093/genetics/28.6.491

24. Narouei M, Ahmadi M, Giacinto G, Takagibi H, Sami A. DLLMiner: structural mining for malware detection. Secur Commun Networks. 2015;8(18):3311–3322. doi:10.1002/sec.1255

25. Lauring AS, Andino R. Quasispecies theory and the behavior of RNA viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(7):e1001005. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001005

26. CDC. Science brief: Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/. Accessed December 2, 2021.

27. COVID CDC, Team R. SARS-CoV-2 B. 1.1. 529 (Omicron) Varianthe t—the United States, December 1 –8, 2021. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(50):1731. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7050e1

28. Walensky RP, Del Rio C. From mitigation to containment of the COVID-19 pandemic: putting the SARS-CoV-2 genie back in the bottle. JAMA. 2020;323(19):1889–1890. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6572

29. Haldane V, De Foo C, Abdalla SM, et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat Med. 2021;27(6):964–980. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01381-y

30. Le K, Nguyen M. The psychological burden of the COVID-19 pandemic severity. Econ Hum Biol. 2021;41:100979. doi:10.1016/j.ehb.2021.100979

31. Stock PG, Wall A, Gardner J, et al. Ethical issues in the COVID era: doing the right thing depends on location, resources, and disease burden. Transplantation. 2020;104(7):1316. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000003291

32. Togun T, Kampmann B, Stoker NG, Lipman M. Anticipating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on TB patients and TB control programmes. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2020;19(1):1–6. doi:10.1186/s12941-020-00363-1

33. Biswas RK, Huq S, Afiaz A, Khan HTA. A systematic assessment of COVID‐19 preparedness and transition strategy in Bangladesh. J Eval Clin Pract. 2020;26(6):1599–1611. doi:10.1111/jep.13467

34. Jamison AM, Quinn SC, Freimuth VS. “You don’t trust a government vaccine”: narratives of institutional trust and influenza vaccination among African American and white adults. Soc Sci Med. 2019;221:87–94. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.12.020

35. Wigle J, Coast E, Watson-Jones D. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine implementation in low and middle-income countries (LMICs): health system experiences and prospects. Vaccine. 2013;31(37):3811–3817. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.06.016

36. Joseph NP, Clark JA, Mercilus G, Wilbur M, Figaro J, Perkins R. Racial and ethnic differences in HPV knowledge, attitudes, and vaccination rates among low-income African-American, Haitian, Latina, and Caucasian young adult women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2014;27(2):83–92. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2013.08.011

37. Falcó‐Pegueroles A, Zuriguel‐Pérez E, Via‐Clavero G, Bosch‐Alcaraz A, Bonetti L. Ethical conflict during COVID‐19 pandemic: the case of Spanish and Italian intensive care units. Int Nurs Rev. 2021;68(2):181–188. doi:10.1111/inr.12645

38. Christaki E. New technologies in predicting, preventing and controlling emerging infectious diseases. Virulence. 2015;6(6):558–565. doi:10.1080/21505594.2015.1040975

39. Diekmann O, Heesterbeek H, Britton T. Mathematical Tools for Understanding Infectious Disease Dynamics. Princeton University Press; 2012.

40. Heesterbeek H, Anderson RM, Andreasen V, et al. Modeling infectious disease dynamics in the complex landscape of global health. Science. 2015;347(6227):aaa4339. doi:10.1126/science.aaa4339

41. Vynnycky E, White R. An introduction to infectious disease modelling. In: OUP oxford; 2010:13.

42. Wang P, Jia J. Stationary distribution of a stochastic SIRD epidemic model of Ebola with double saturated incidence rates and vaccination. Adv Differ Equ. 2019;2019:433. doi:10.1186/s13662-019-2352-5

43. Anastassopoulou C, Russo L, Tsakris A, Siettos C. Data based analysis, modelling and forecasting of the COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0230405. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230405

44. Yuan M, Yin W, Tao Z, Tan W, Hu Y. Association of radiologic findings with mortality of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0230548. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230548

45. Heaton PM, Douoguih M. Booster dose of Janssen COVID-19 Vaccine (Ad26. COV2. S) following primary vaccination; 2021.

46. Flacco ME, Soldato G, Martellucci CA, et al. Interim Estimates of COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness in a Mass Vaccination Setting: data from an Italian Province. Vaccines. 2021;9:628. doi:10.3390/vaccines9060628

47. Kissling E, Hooiveld M, Martı´n VS, et al. Vaccine effectiveness against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults aged 65 years and older in primary care: i-MOVE-COVID-19 project, Europe, December 2020 to May 2021. Eurosurveillance. 2021;26:2100670. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES

48. Bernal JL, Andrews N, Gower C, et al. Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines on covid-19 related symptoms, hospital admissions, and mortality in older adults in England: test negative case-control study. BMJ. 2021;373:373. PMID: 33985964.

49. Martı´nez-Baz I, Miqueleiz A, Casado I, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing SARS CoV-2 infection and hospitalisation, Navarre, Spain, January to April 2021. Eurosurveillance. 2021;26:2100438. PMID: 34047271. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.21.2100438

50. Pritchard E, Matthews PC, Stoesser N, et al. Impact of vaccination on new SARS-CoV-2 infections in the United Kingdom. Nat Med. 2021;27:1370–1378. PMID: 34108716. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01410-w

51. Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, et al. Interim Estimates of vaccine effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccines in Preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection among health care personnel, first responders, and other essential and frontline workers—Eight U.S. Locations. 2021;70:495–500. PMID: 33793460. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e3

52. Amit S, Regev-Yochay G, Afek A, et al. Early rate reductions of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 in BNT162b2 vaccine recipients. Lancet. 2021;397:875–877. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736

53. Jara A, Undurraga EA, Gonza´lez C, et al. Effectiveness of an Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine in Chile. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:875–884. PMID: 34233097. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2107715

54. Harris RJ, Hall JA, Zaidi A, et al. Effect of Vaccination on Household Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in England. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:759–760. PMID: 34161702. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2107717

55. Thompson MG, Burgess JL, Naleway AL, et al. Prevention and Attenuation of Covid-19 with the BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 Vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:320–329. PMID: 34192428. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2107058

Kofi Annan’s call to bring all stakeholders around the table — including the private sector, local authorities, civil society organisations, academia, and scientists — resonates now more than ever with so many, who understand that governments alone cannot shape our future.

Kofi Annan’s call to bring all stakeholders around the table — including the private sector, local authorities, civil society organisations, academia, and scientists — resonates now more than ever with so many, who understand that governments alone cannot shape our future.

This deliberate slew of measures of discrimination against Afghanistan’s women and girls is also a terrible act of self-sabotage for a country experiencing huge challenges including from climate-related and natural disasters to exposure to global economic headwinds that leave some 25 million Afghan people in poverty and many hungry.

This deliberate slew of measures of discrimination against Afghanistan’s women and girls is also a terrible act of self-sabotage for a country experiencing huge challenges including from climate-related and natural disasters to exposure to global economic headwinds that leave some 25 million Afghan people in poverty and many hungry.