The G20 or Group of Twenty is an intergovernmental forum comprising 19 countries and the European Union. It works to address major issues related to the global economy, such as international financial stability, climate change mitigation, and sustainable development.

By Ian Mitchell and Sam Hughes

LONDON, Feb 23 2023 (IPS)

It’s been 25 years since the 1997 Asian financial crisis led to the creation of the G20 forum for finance ministers; and 15 years since this became a leader-level meeting following the global financial crisis. During this period, there has been significant shift in the global finance and economic landscape.

The ascent of several emerging economies has seen their contributions to the multilateral finance system that supports development rise significantly. Our new report collates those contributions over the last decade for the first time. It charts how China’s annual contributions to the UN and multilateral development banks rose twenty-fold from $0.1bn to $2.2bn.

But it also looks collectively at a group of 13 rising economies whose developmental contributions to multilateral finance institutions have risen five-fold to over $6bn over the last decade.

These contributions now make up an eighth of the total; and have seen the creation of two new multilateral finance institutions.

In this piece, we draw out key findings from our analysis, including the balance between funding existing and new institutions like the New Development Bank.

We consider whether continued growth in the 13 emerging actors could generate enough new funding for development over the next quarter century, and even create an institution as large at the World Bank’s fund for low-income countries (IDA).

Despite recent rhetoric around the return to a bipolar world order, this report is evidence that a wide group of countries are already playing major role in the global economic and development system, and will continue to do so in years to come

The transformational effect of economic growth on the multilateral system

In 1990 most people in the world lived in low-income countries; by 2020, this share had fallen dramatically to just seven percent of people. Meanwhile, the share of the global population living in middle-income countries swelled from 30 percent in 1990 to 73 percent in 2020.

Such a transformation implies a greater number of countries with the economic output to contribute internationally: widening and deepening participation in the multilateral system.

And this is just what we’ve seen. Over the decade to 2019, we find a group of emerging actors have significantly increased their contributions of development finance to multilateral organisations.

These include thirteen major economies outside the group of more established providers within the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), which tend to receive more attention.

Ten of these emerging actors are G20 members, including the BRICS—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—but others have grown quickly too: Argentina, Chile, Indonesia, Israel, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates. Collectively, we refer to these thirteen emerging actors as the “E13.”

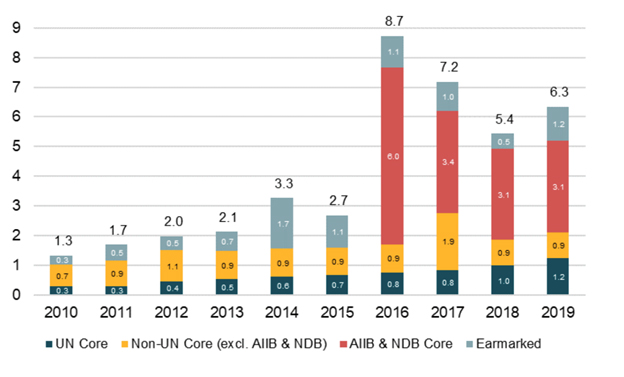

Over the decade, the E13’s annual contributions of development finance to multilateral organisations (both core and funding earmarked for particular purposes) have increased almost five-fold, from $1.3bn in 2010 to $6.3bn in 2019 (up 377 percent). And their unrestricted core contributions have risen even more: increasing from $1.0bn to $5.2bn (up 410 percent).

Of these core contributions, we see that those to UN agencies more than quadrupled over the decade, steadily rising from $0.3bn to $1.2bn (up 330 percent). But by far the most striking development in E13 core contributions has come from the creation and capitalisation of two new multilateral organisations: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the New Development Bank (NDB).

The role of China

Although China has recently stepped back its bilateral finance efforts, its multilateral contributions increased steadily to 2019; and provided a third (34 percent) of the E13 total over the decade. Our colleagues have examined this in detail, including how China has the second highest aggregate voting share after the US in international finance institutions it supports.

Still, our analysis also highlights the importance of Russia, Brazil and India who each contributed over $3bn over the period and collectively contributed a further third of the total. While China’s multilateral contributions have been concentrated (59 percent) in new institutions it co-founded (see below), other providers have concentrated funding in traditional institutions: for example, Argentina, Chile and Mexico did not support the new institutions while for Saudi Arabia and UAE they were 17 percent and 21 percent respectively.

Creating new multilateral finance organisations

Over the ten-year period we examine, almost half of the E13’s core multilateral contributions were to the two new institutions (AIIB and NDB). After 2016, funding provided to these institutions made up over two-thirds of their contributions. Indeed, in 2016 the first financial contributions to AIIB and NDB causedE13 multilateral development finance to triple in a single year.

The E13 provided an additional $6.0bn of core funds for AIIB and NDB in 2016, without reducing their multilateral contributions through other channels.

Though annual contributions reduced to $3.1bn in 2019, AIIB and NDB still accounted for half of the E13’s multilateral development finance in that year, leaving their contributions at the end of the decade far ahead of the beginning.

Figure 1. E13 core and earmarked contributions of development finance to multilateral organisations (nominal USD billions)

Source: Authors’ analysis

Emerging actors fund a sixth of the UN system

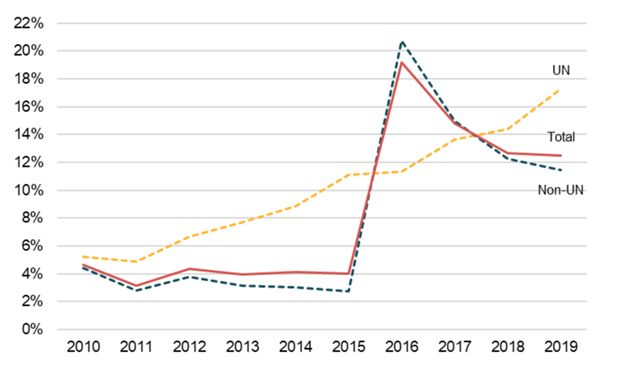

As well as higher absolute contributions (Figure 1), the E13’s role in the multilateral system has also grown in relative terms (Figure 2). As a share of the level of finance provided by the 29 high-income countries in the OECD DAC, the E13’s core multilateral contributions rose from 5 percent in 2010 to 12 percent in 2019—more than doubling their relative significance.

This was largely due to the effect of AIIB and NDB (clearly seen by the 2016 peak), but we also see that E13 core contributions to the UN system steadily and quickly rose as a share of the DAC level across the decade: from 5 percent in 2010 to 17 percent in 2019.

Figure 2. E13 core contributions of development finance to multilateral organisations as a share of contributions from DAC countries

Source: Authors’ analysis

A look to 2050—what role might the emerging economies play?

As the economies of the E13 continue to grow, what might this mean for their multilateral contributions in the future? Figure 3 shows how the share of economic output provided as development finance to multilateral organisations (either core or earmarked) tends to increase with higher levels of income per capita.

Though the relationship is steeper for the DAC than the E13, even the E13’s current trajectory implies a significant increase in future multilateral development finance from this group.

Ian Mitchell is Co-Director, Development Cooperation in Europe and Senior Policy Fellow at the Center for Global Development. Sam Hughes is a Research Assistant at the Center for Global Development.

IPS UN Bureau