Climate Action, Climate Change, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Environment, Featured, Food and Agriculture, Global, Headlines, Innovation, Sustainability, Sustainable Development Goals, TerraViva United Nations

Conscious Food Systems Alliance (CoFSA) promotes consciousness as a key evidence-based practice to support systemic change – reframing how people think about food to unlock food systems transformation, nourishing all people, and regenerating planet Earth. Pictured here a farmer in Katfoura village on the Tristao Islands in Guinea benefits from opportunities to generate income and improve community life. Credit: UN Women/Joe Saade

– Deep in the Egyptian desert, the SEKEM community celebrates its first wheat crop – grown to alleviate shortages and price increases caused by the war in Ukraine, and the latest crop in a 46-year history of regenerative development, which has effectively made the desert bloom. On another continent, a consumer who buys acai collected and produced by the Yawanawá in Brazil helps protect 200,000 acres of land.

Food connects people, cultures, and planet Earth. But rather than nourishing global health and well-being, food systems remain at the heart of the global community’s social and environmental crises today.

Massive investment and efforts to transform food systems and existing policy and technical solutions are not delivering the desired impact. In the face of the global food systems crises manifested in food insecurity, unsustainable agricultural practices, and climate change, re-examining the origins of ongoing crises and barriers to transformation is critical.

Reframing How People Think About Food

Against this backdrop, the Conscious Food Systems Alliance (CoFSA) promotes consciousness as a key evidence-based practice to support systemic change. The alliance is built on the premise that reframing how people think about food is the key to unlocking food systems transformation, nourishing all people, and regenerating planet Earth.

“We know our food systems are in a critical state and sit at the core of the regeneration process this world greatly needs, and we believe this can only happen with a change of mindsets and heart-sets, with different values and worldviews,” says Thomas Legrand, CoFSA Lead Technical Advisor.

Convened by UNDP, CoFSA is a movement of food, agriculture, and consciousness practitioners united around a common goal: to support people from across food and agriculture systems to cultivate the inner capacities that activate systemic change and regeneration.

The alliance aims to leverage “the power of consciousness and inner transformation, including proven approaches such as mindfulness, compassion, systems leadership, indigenous and feminine wisdoms, to support systemic change towards sustainability and human flourishing in the food and agriculture sector.”

CoFSA Challenge Fund to Support Regenerative Food System Projects

The CoFSA Challenge Fund, which is about to be launched, intends to support the development of strategic, innovative ideas and solutions to scale up and accelerate progress toward the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development through the transformation of food systems, which is critical to achieving the UN’s SDGs.

The Challenge Fund focuses on cultivating inner capacities for regenerative food systems. This constitutes a new field of practice that requires testing and innovation to identify, develop and nurture potentially transformative solutions.

In this first round of calls for proposals, UNDP will support approximately four pilot projects of up to USD 20,000.

[embedded content]

Conscious Food System Links Supply Chain

A conscious food system is a holistic approach to the well-being of people and ecosystems, and where there is a connection and awareness between stakeholders across the whole supply chain, says Helmy Abouleish, SEKEM’s CEO. He heads the holistic, sustainable development community established in 1977 by his father, Dr Ibrahim Abouleish, in the Egyptian desert.

According to UNDP, to transform the systems that harm people and the planet and how food is produced and consumed, “We need to look beyond the problems’ symptoms and even systems’ patterns and structures, at what fundamentally drives the systems.”

Consciousness and mental models, or regenerative mindsets and cultures, are increasingly recognized as the key to unlocking systems change in food and agriculture. To this end, CoFSA applies consciousness approaches to technical solutions to support the cultivation and consideration of inner capacities based on the premise that sustainable change comes from within.

Christine Wamsler, Professor of Sustainability Science at LUND University, emphasizes that there is “increasing scientific consensus that creating sustainable, regenerative systems do not only require a change in our external worlds. Instead, it has to go hand-in-hand with a fundamental shift in our relationships — in the way we think about ourselves, each other, and life as a whole.”

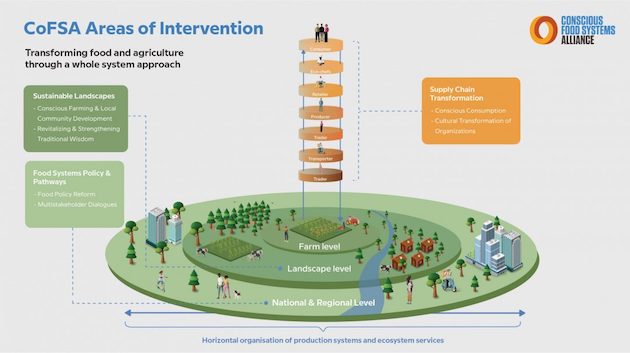

Graphic representation of the Conscious Food Systems Alliance (CoFSA) concept. Credit: UNDP/CoFSA

Similarly, senior lecturer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Otto Scharmer, stresses, “You cannot change a system unless you change the mindsets or the consciousness of the people who are enacting that system.”

At the heart of it, mindful eating and activating transformation from the inside is a recognition that changing behavior is, at times, more about identity, emotions, and connections than data and analyses in the same way elections are campaigned and won against a backdrop of long-held beliefs and opinions.

Question Impact of Consumer Choices

“I think today, whatever you eat, however you dress, you need to ask yourself where they come from, what kind of impact they are giving back to the Mother Earth, cultural, economic, and spiritual environment,” says Tashka Yawanawá, Chief of the Yawanawá that has survived for centuries in the Brazilian rainforests.

Awareness of the people and processes in food and agriculture systems aligns with indigenous wisdom and is at the heart of the approach taken by the Yawanawá people. For instance, Tashka Yawanawá says: “When somebody drinks the acai collected and produced by the Yawanawá, they’re helping protect 200,000 acres of land.”

“They are also supporting the preservation of our language, our culture, our cultural and spiritual manifestation. Making that link gives value to where you source these products from … when you buy acai made by Yawanawá, you have an awareness that you’re supporting conscious food.”

UNDP stresses that farmers’ lives depend on being seen as human beings, not just economic agents, and says it is “Time to build safe, reflective and connecting spaces to engage in the deep conversations we need for right relationships to replace market rules.”

In the world of conscious thinking and mindful eating, everyone has a role.

A marker trader at a vegetable stall in the village of El-Maadi near Cairo with heaps of fresh vegetables. CoFSA aims to renew lost ties between producers, the foods they grow, cooks, and consumers. Credit: Gavin Bell

Teresa Corção, founder of Instituto Maniva, a non-profit in Brazil that values traditional food knowledge and renews the ties lost between producers, the foods they grow, cooks, and consumers, says chefs have a critical role in listening more to the people who grow the food.

“I think we all see now more and more we need other ways of both changing ourselves and helping others change the way they think in order for us to have the right mindsets to make choices that are more sustainable,” says Andrew Bovarnick, UNDP’s Food, and Agricultural Commodity Systems, Global Head.

CoFSA is built on bringing consciousness to food systems to support the transition to a holistic, bio-regional approach and creating productive landscapes of regeneration.

That consciousness can help restore the balance in food systems between food production, conservation, and well-being, support the uptake of agroecological practices which regenerate the soil, and strengthen the capacity of food to distribute wealth and well-being in communities.

IPS UN Bureau Report