Civil Society, Climate Action, Climate Change, Conferences, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Energy, Environment, Featured, Global, Global Governance, Headlines, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, Poverty & SDGs, Regional Categories

One of the family photos taken after the laborious end of the 26th climate summit in Glasgow, which closed a day later than scheduled with a Climate Pact described as falling short by even the most optimistic, lacking important decisions to combat the crisis and without directly confronting fossil fuels, the cause of the emergency. CREDIT: UNFCCC

– Developing countries will surely remember the Glasgow climate summit, the most important since 2015, as a fiasco that left them as an afterthought.

That was the prevailing sentiment among delegates from the developing South during the closing ceremony on the night of Saturday Nov. 13, one day after the scheduled end of the conference.

Bolivia’s chief negotiator, Diego Pacheco, questioned the outcome of the summit. “It is not fair to pass the responsibility to developing countries. Developed countries do not want to acknowledge their responsibility for the crisis. They have systematically broken their funding pledges and emission reduction commitments,” he told IPS minutes after the end of the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) on climate change in Glasgow.

The 196 Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) ignored the public clamor, which took shape in the demands of indigenous peoples, young people, women, scientists and social movements around the world for substantive measures to combat the climate crisis, even though the goal of containing global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius is barely surviving on life support.

The Glasgow Climate Pact that came out of the summit finally mentions the need to move away from the use of coal. But it had to water down the stronger recommendation to “phase out” in order to overcome the last stumbling block.

In addition, COP26 broke a taboo, albeit very tepidly, after arduous marches and counter-marches in the negotiating room and in the three drafts of the Glasgow Pact: there was a mention of fossil fuels as part of the climate emergency. And it also stated the need to reduce “inefficient” subsidies for fossil fuels.

But the summit, where decisions are made by consensus, avoided a strong stance in this regard. It also avoided moving from recommendations to obligations for the next edition, to be held in Egypt, and those that follow, while the climate crisis continues causing severe droughts, devastating storms, melting of the polar ice caps and warming of the oceans.

In a plenary session that was delayed by several minutes, the final declaration underwent a last-minute change when India, one of the villains of the meeting – along with Saudi Arabia, Australia and Russia – asked for the phrase “phasing out” of coal to be replaced by “phasing down”, a change questioned by countries such as Mexico, Liechtenstein and Switzerland.

A paradoxical fact at the close of COP26, where civil society organizations complained that they were left out, was the decision of several countries to endorse the final text even though they differed on several points, including the fossil energy face-lifts.

“Today, we can say with credibility that we have kept 1.5 degrees within reach. But its pulse is weak. And it will only survive if we keep our promises. If we translate commitments into rapid action,” said conference chairman Alok Sharma, choking back tears after a pact – albeit a minimal one – was reached by negotiating three drafts and holding arduous discussions on the fossil fuel question, right up to the final plenary.

COP26 chair Alok Sharma blinked back tears during his closing speech at the climate summit, expressing the tension of negotiating the Glasgow Climate Pact, due to the hurdles thrown in the way of a consensus by the big coal and oil producers. CREDIT: UNFCCC-Twitter

The South is still waiting

Lost amidst the impacts of the climate emergency and forgotten by the industrialized countries, the global South failed to obtain something vital for many of its nations: a clear plan and funding for loss and damage, an issue that was deferred to COP27 in Egypt.

Mohamed Adow, director of the non-governmental Power Shift Africa, said the pact is “not good enough…There is no mention of solidarity and justice. We need a clear process to face loss and damage. There should be a link between emission reduction, financing and adaptation.”

The final decision by China, the United States, India and the European Union to turn their backs on a global fossil fuel exit and deny climate support to the most vulnerable nations left the developing world high and dry.

“There are things that cannot wait to COP27 or 2025. To face loss and damage, the most vulnerable countries need financing to battle the impacts on their territories,” Manuel Pulgar-Vidal, global climate and energy leader for the non-governmental World Wildlife Fund, told IPS.

Climate policies were, at least on the agenda, the focus of COP26.

The summit focused on carbon market rules, climate finance of at least 100 billion dollars per year, gaps between emission reduction targets and needed reductions, strategies for carbon neutrality by 2050, adaptation plans, and the working platform for local communities and indigenous peoples.

But the goal of hundreds of billions of dollars per year has been postponed, a reflection of the fact that financing for climate mitigation and adaptation is a touchy issue, especially for developed countries.

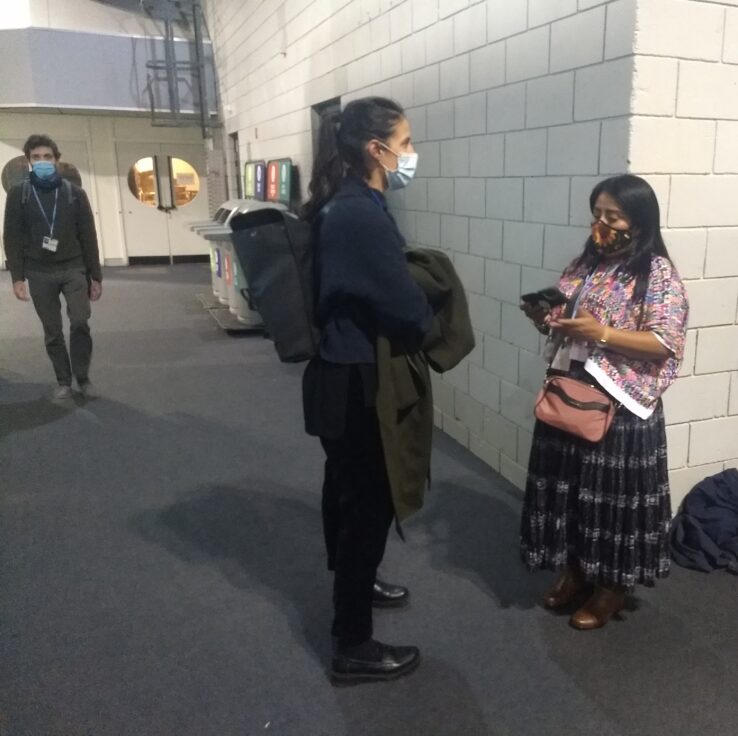

The corridors of the Blue Zone of the Scottish Events Campus, where the official part of the 26th Climate Conference was held in the city of Glasgow, were emptying on Saturday Nov. 13, at the end of the summit, which lasted a day longer than scheduled and ended with a negative balance according to civil society organizations. CREDIT: Emilio Godoy/IPS

Offers and promises – on paper

One breakthrough at COP26 was the approval of the rules of the Paris Agreement, signed in the French capital in December 2015, at COP21, to form the basis on which subsequent summits have revolved. By 2024, all countries will have to report detailed data on emissions, which will form a baseline to assess future greenhouse gas reductions.

The agreement on the functioning of carbon markets creates a trading system between countries, but does not remove the possibility of countries and companies skirting the rules.

Industrialized countries committed to doubling adaptation finance by 2025 based on 2019 amounts. In addition, COP26 approved a new work program to increase greenhouse gas cuts, with reports due in 2022.

It also asked the UNFCCC to evaluate climate plans that year and its final declaration calls on countries to switch from coal and hydrocarbons to renewable energy.

Apart from the Climate Pact, the summit produced voluntary commitments against deforestation, emissions of methane, a gas more polluting than carbon dioxide, and the phasing out of gasoline and diesel vehicles.

In addition, at least 10 countries agreed to put an end to the issuing of new hydrocarbon exploration and exploitation licenses in their territories.

Furthermore, some thirty nations agreed to suspend public funding for coal, gas and oil by 2022.

Demonstrations demanding ambitious, substantive and equitable measures to address the climate crisis continued throughout the 14-day climate summit in Glasgow, which ended on the night of Saturday Nov. 13 with disappointing results for the global South. CREDIT: Emilio Godoy/IPS

Finally, more than 100 stakeholders, including countries and companies, signed up to the elimination of cars with internal combustion engines by 2030, without the major automobile manufacturers such as Germany, Spain and France joining in, and a hundred nations signed a pact to promote sustainable agriculture.

All of the 2030 pledges, which still need concrete plans for implementation, imply a temperature rise of 2.8 degrees C by the end of this century, according to the independent Climate Action Tracker.

The climate plans of the 48 least developed countries (LDCs) would cost more than 93 billion dollars annually, the non-governmental International Institute for Environment and Development said in Glasgow.

In addition, annual adaptation costs in developing countries would be about 70 billion dollars, reaching a total of 140 to 300 billion dollars by 2030, according to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP).

But the largest disbursements are related to loss and damage, which would range between 290 billion and 580 billion dollars by 2030, and hence the enormous concern of these nations to obtain essential financing, according to a 2019 study. And their disappointment with the results of the Oct. 31-Nov.13 conference.

During his presentation at the closing plenary, Seve Paeniu, a climate envoy from Tuvalu, an island nation whose very existence is threatened by the rising sea level, showed a photo of his three grandchildren and said he had been thinking about what to say to them when he got home.

“Glasgow has made a promise to guarantee their future. It will be the best Christmas gift that I can bring home,” he said. But judging by the Climate Pact, Paeniu may have to look for another present.

IPS produced this article with the support of Iniciativa Climática of Mexico and the European Climate Foundation.