Aid, Civil Society, Democracy, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Featured, Global, Global Governance, Headlines, Inequity, Population, Poverty & SDGs, TerraViva United Nations

CHRIS WELLISZ is on the staff of Finance & Development published by the International Monetary Fund*

Credit: IMF

– As a child growing up in Communist Yugoslavia, Branko Milanovic witnessed the protests of 1968, when students occupied the campus of the University of Belgrade and hoisted banners reading “Down with the Red bourgeoisie!”

Milanovic, who now teaches economics at the City University of New York, recalls wondering whether his own family belonged to that maligned group. His father was a government official, and unlike many Yugoslav kids at the time, Milanovic had his very own bedroom—a sign of privilege in a nominally classless society. Mostly he remembers a sense of excitement as he and his friends loitered around the edge of the campus that summer, watching the students sporting red Karl Marx badges.

“I think that the social and political aspects of the protests became clearer to me later,” Milanovic says in an interview. Even so, “1968 was, in many ways, a watershed year” in an intellectual journey that has seen him emerge as a leading scholar of inequality. Decades before it became a fashion in economics, inequality would be the subject of his doctoral dissertation at the University of Belgrade.

Today, Milanovic is best known for a breakthrough study of global income inequality from 1988 to 2008, roughly spanning the period from the fall of the Berlin Wall—which spelled the beginning of the end of Communism in Europe—to the global financial crisis.

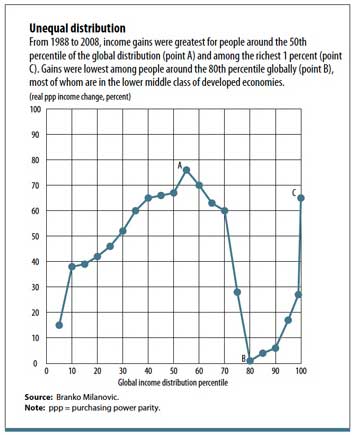

The 2013 article, co-written with Christoph Lakner, delineated what became known as the “elephant curve” because of its shape (see chart). It shows that over the 20 years that Milanovic calls the period of “high globalization,” huge increases in wealth were unevenly distributed across the world.

The middle classes in developing economies—mainly in Asia—enjoyed a dramatic increase in incomes. So did the top 1 percent of earners worldwide, or the “global plutocrats.”

Meanwhile, the lower middle classes in advanced economies saw their earnings stagnate.

Meanwhile, the lower middle classes in advanced economies saw their earnings stagnate.

The elephant curve’s power lies in its simplicity. It elegantly summarizes the source of so much middle-class discontent in advanced economies, discontent that has turbocharged the careers of populists from both extremes of the political spectrum and spurred calls for trade barriers and limits on immigration.

“Branko had a deep influence on global inequality research, particularly with his findings on the elephant curve, which has set the tone for future research,” says Thomas Piketty, author of the bestselling Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Piketty and his collaborators confirmed the findings in a 2018 study, which found that the top 1 percent globally captured twice as much of total growth as the bottom 50 percent from 1980 to 2016.

Milanovic’s findings “appear to be even more spectacular than what was initially suggested,” Piketty says. “The elephant looks more like a mammoth.”

Economists long disdained the study of inequality. Many lived in a theoretical world populated by a mythical figure known as homo economicus, or rational man, whose only attribute was a drive to maximize his well-being. Differences among people, or groups, were irrelevant. Variety was irrelevant. Only averages mattered.

In this world of identical rational actors, the forces of supply and demand worked their magic to determine prices and quantities of goods, capital, and labor in a way that maximized welfare for society as a whole. The distribution of wealth or income didn’t fit into the picture. It was simply a by-product of market forces.

“The market solves everything,” Milanovic says. “So the topic really was not—still is not—totally mainstream.”

Then came the global financial crisis of 2008, and with it “the rise of the realization that the top 1 percent or the top 5 percent have really vastly outstripped, in income growth, the middle class,” he says.

The study of inequality also got a boost from the explosion of data that can be mined with evermore powerful computers, making it easier to divide the anonymous masses of consumers and workers into groups with common characteristics. Big data, he says, “enables the study of heterogeneity, and inequality is by definition heterogenous.”

Data has always been one of Milanovic’s passions, alongside his interest in social classes, which flourished during his high school years in Brussels, where his economist father was posted as Yugoslav envoy to the then–European Economic Community.

“High school in Belgium—and I think it was the same in France—was very Marxist,” he says.

His classmates were divided between leftist kids, influenced by the student movements of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and “bourgeois” kids. As the privileged son of a diplomat representing an ostensibly workers’ government, young Branko didn’t quite fit either category. “It was a very peculiar situation,” he says.

At university in Belgrade, Milanovic initially leaned toward philosophy but decided economics would be more practical. It also offered a way to combine his interests in statistics and social classes.

Graduate studies led to a fellowship at Florida State University in Tallahassee, where he was impressed by American abundance—huge portions of inexpensive food, free refills of coffee, big cars—alongside stark income inequality and racial discrimination.

Two years later, he was back in Belgrade to work on his doctoral dissertation on inequality in Yugoslavia, mining rare household survey data supplied by a friend who worked in the federal statistical office.

While his dissertation raised eyebrows in Marxist Yugoslavia—along with his decision to avoid joining the Communist Party—it launched a two-decade career at the World Bank’s Research Department.

“Branko was really one of the leading experts, even at that time, on income distribution,” says Alan Gelb, who hired Milanovic to join a small team studying the transition to market economies in post-Communist eastern Europe. Milanovic focused on issues of poverty and income distribution.

The wealth of data the World Bank collects was a priceless resource, and it inspired Milanovic to carry out cross-country comparisons of inequality, which were a novelty. One day in 1995, Milanovic was talking with Gelb’s successor as the head of his unit.

“I suddenly had this idea: ‘Look, we have all this data from around the world. We study individual countries, but we never put them together.’ ” Four years later, he published the first study of global income distribution based on household surveys.

In the years that followed, Milanovic published widely and profusely. Alongside his work on post-Communist economies, he continued to explore inequality and its link with globalization. His articles and books display the broad range of his interests, which include history, literature, and sports.

In one article, he estimates the average income and inequality level in Byzantium in the year 1000. Another looks at the links between labor mobility and inequality in soccer, which he calls the most globalized sport.

He found that club soccer has become very unequal because a dozen top European teams can afford to recruit the world’s best players. On the other hand, the free movement of soccer players has reduced inequality among national teams. The reason: players from small countries can hone their skills at top club teams, then return home to compete for their national teams.

Literary conversations with his wife, Michele de Nevers, a specialist in climate finance at the Center for Global Development, inspired him to write an offbeat analysis of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice.

Arguing that the book is as much about money as love, he estimates the incomes of various characters and looks at how wealth influences the choice of mates for Austen’s protagonist, Elizabeth Bennet.

He did the same for Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. Both essays were published in Milanovic’s 2011 book, The Haves and the Have-Nots: A Brief and Idiosyncratic History of Global Inequality .

Another book, Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, was a milestone that synthesized years of his scholarship on inequality within and among countries since the Industrial Revolution.

In contrast to Piketty, who argues that inequality inexorably widens under capitalism, Milanovic sees it moving in waves or cycles under the influence of what he calls benign and malign forces.

In advanced economies, income disparity widened in the 19th and early 20th centuries until the malign forces of war and hyperinflation reduced it by destroying wealth. After World War II, benign forces such as progressive taxation, more powerful labor unions, and more widely accessible education pushed inequality down.

The fall of the Berlin Wall was a watershed. It brought the former Soviet bloc states into the global economy at a time when China also began opening up. Rapid growth in the developing world narrowed inequality between countries while widening it in the developed world, where middle-class incomes stagnated as the wealthy prospered.

What does the future hold? It looks good for much of the developing world and especially Asia, which will continue to catch up with the rich countries. In advanced economies, on the other hand, the outlook seems grimmer.

There, the twin forces of globalization and technological innovation will continue to squeeze the middle class. Social mobility will decline as an entrenched elite benefits from greater access to expensive higher education and wields its political clout to enact “pro-rich” policies, such as favorable tax regimes.

As income disparities grow, so will social tensions and political strife—a prognosis confirmed by events such as Brexit and protests in France that have occurred since the book’s publication in 2016.

Milanovic worries that this friction might lead to a “decoupling” of democracy and capitalism, resulting in plutocracy in the United States and populism or nativism in Europe.

While there has been considerable debate about inequality over the past decade, “nothing has really moved” in policy terms, he says. “We are on this automatic pilot which basically leads to higher inequality. But I am not totally losing faith.”

The traditional answer—redistribution of income—won’t work as well as it did in the past because of the mobility of capital, which allows the wealthy to shelter their incomes in tax havens. Instead, policy should aim for a redistribution of “endowments” such as wealth and education.

Measures would include higher inheritance taxes, policies that encourage companies to distribute shares to workers, and increased state funding for education.

“We cannot achieve that tomorrow,” he says. “But I think we should have an idea that we want to move to a capitalist world where endowments would be much more equally distributed than today.”

Milanovic also takes on the nettlesome issue of inequality between countries. He calculates that an American, simply by virtue of being born in the United States, will earn 93 times more than a person born in the world’s poorest country.

This is what Milanovic calls the “citizenship premium,” and it gives rise to pressure for migration as people born in poor countries seek their fortunes in richer ones.

Milanovic argues that halting migration is no more feasible than halting the movement of goods or capital. Yet it’s also unrealistic to expect citizens of advanced economies to open their borders. His solution: allow more immigrants but deny them the full rights of citizenship, and perhaps tax them to compensate citizens displaced in the labor force.

His current work, in a way, brings him back to his roots in Yugoslavia. It involves the study of class structure in the People’s Republic of China and, in particular, a close look at the top 5 percent of the income distribution. It forms a part of his next book, Capitalism, Alone, which argues that China has developed a distinct form of capitalism that will coexist with its liberal forebear.

Where is the study of inequality headed? Milanovic sees two frontiers, both driven by the availability of new data. One is wealth inequality, à la Piketty; the other is intergenerational inequality, a subject plumbed by economists such as Harvard’s Raj Chetty.

The two areas “appeal to young people who are now very socially aware,’’ he says. “On the other hand, they are very smart and want to work on tough topics.” He adds, “I am very optimistic in that sense.”

*Opinions expressed in articles and other materials are those of the authors; they do not necessarily reflect IMF policy.