Armed Conflicts, Climate Change, Combating Desertification and Drought, Conferences, Conservation, Editors’ Choice, Environment, Featured, Global, Headlines, Migration & Refugees, Natural Resources, Sustainable Development Goals, TerraViva United Nations

Collecting water in Ethiopia. A new report, ‘Global Water Bankruptcy: Living Beyond Our Hydrological Means in the Post Crisis Era’ warns that many of the earth’s water resources have been pushed to a point of permanent failure. Credit: EU/ECHO/Anouk Delafortrie/IPS

– The world has entered what United Nations researchers now describe as an era of Global Water Bankruptcy, a condition where humanity has irreversibly overspent the planet’s water resources, leaving ecosystems, economies, and communities unable to recover to previous levels.

The new report, released by the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health, titled Global Water Bankruptcy: Living Beyond Our Hydrological Means in the Post-Crisis Era. The report argues that decades of overextraction, pollution, land degradation, and climate stress have pushed large parts of the global water system into a permanent state of failure.

“The world has entered the era of Global Water Bankruptcy,” the report reads, adding that “in many regions, human water systems are already in a post-crisis state of failure.”

According to the report, the language of “water crisis” is no longer sufficient to explain what is happening. A crisis implies a shock followed by recovery. Water bankruptcy, by contrast, describes a condition where recovery is no longer realistically possible because natural water capital has been permanently damaged.

In an exclusive interview with Inter Press Service, former Deputy Head of Iran’s Department of Environment Prof. Kaveh Madani, who currently is the Director at United Nations University, Institute for Water, Environment and Health, said that declaring that the planet has entered the era of water bankruptcy must not be interpreted as universal water bankruptcy, as not all basins, aquifers, and systems are water bankrupt.

Prof. Kaveh Madani, Director at the United Nations University, Institute for Water, Environment and Health, addresses the UN midday press briefing. Credit: IPS

“But we now have enough critical basins and aquifers in chronic decline and showing clear signs of irreversibility that the global risk landscape is already being reshaped. Scientifically, we know recovery is no longer realistic in many systems when we see persistent overshoot (using more than renewable supply) combined with clear markers of irreversibility—for example aquifer compaction and land subsidence that permanently reduce storage, wetland and lake loss, salinization and pollution that shrink usable water, and glacier retreat that removes a long-term seasonal buffer. When these signals persist over time, the old “bounce back” assumption stops being credible,” Madani said.

According to the report, over decades, societies have drawn down the renewable flow of rivers and rainfall besides long-term reserves stored in aquifers, glaciers, wetlands, and soils. At the same time, pollution and salinization have reduced the share of water that is safe or economically usable.

“Over decades, societies have withdrawn more water than climate and hydrology can reliably provide, drawing down not only the annual income of renewable flows but also the savings stored in aquifers, glaciers, soils, wetlands, and river ecosystems,” the report says.

The scale of the problem, as per the report, is global. Nearly three-quarters of the world’s population now lives in countries classified as water insecure or critically water insecure.

Around 2.2 billion people still lack safely managed drinking water, while 3.5 billion lack safely managed sanitation. About 4 billion people, as per the report findings, experience severe water scarcity for at least one month every year.

Madani said, adding that water bankruptcy is best assessed basin by basin and aquifer by aquifer, not by country.

“Please note that, based on the water security definition used by the UN system, water insecurity and water bankruptcy are not equivalent. Water bankruptcy can drive water insecurity, but water insecurity can also stem from limited financial and institutional capacity to build and operate infrastructure for safe water supply and sanitation, even where physical water is available,” he explained.

Madani added that the regions most consistently closest to irreversible decline cluster in the Middle East and North Africa, Central and South Asia, parts of northern China, the Mediterranean and southern Europe, the southwestern United States and northern Mexico (including the Colorado River system), parts of southern Africa, and parts of Australia.

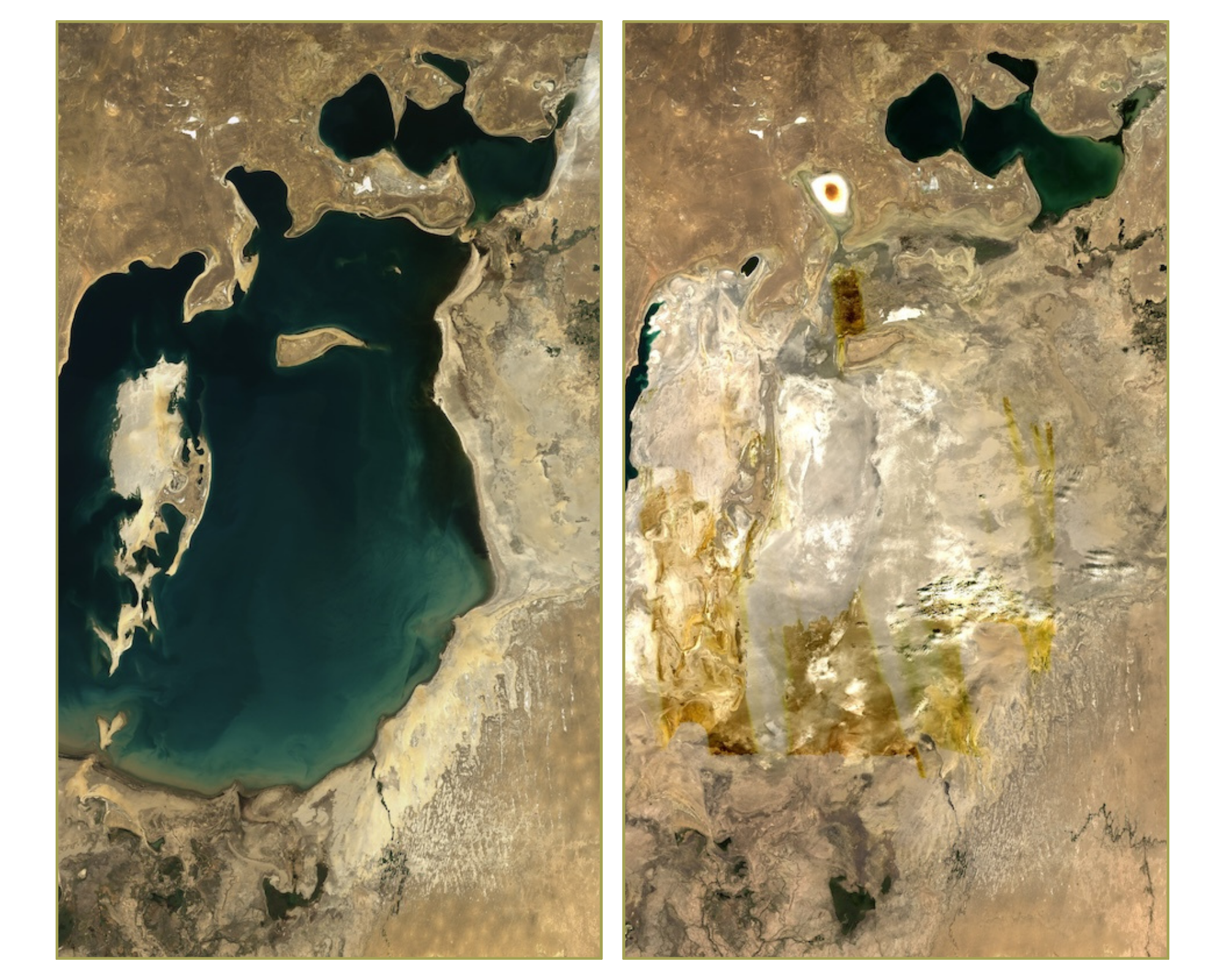

The Aral Sea, which lies between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, shows dramatic water loss between 1989 and 2025. Credit: UNU-INWEH

Surface Water Systems Are Shrinking Rapidly

The report shows how more than half of the world’s large lakes have lost water since the early 1990s, affecting nearly one quarter of the global population that depends directly on them. Many major rivers now fail to reach the sea for parts of the year or fall below environmental flow needs.

Massive losses have occurred in wetlands, which serve as natural buffers against floods and droughts. Over the past five decades, the report claims that the world has lost roughly 410 million hectares of natural wetlands, almost the size of the European Union. The economic value of lost ecosystem services from these wetlands exceeds 5.1 trillion US dollars.

Groundwater depletion is one of the clearest signs of water bankruptcy. Groundwater, says the report, now supplies about 50 percent of global domestic water use and over 40 percent of irrigation water. Yet around 70 percent of the world’s major aquifers show long-term declining trends.

“Excessive groundwater extraction has already contributed to significant land subsidence over more than 6 million square kilometers,” the report says, warning that in some locations land is sinking by up to 25 centimeters per year, permanently reducing storage capacity and increasing flood risk.

In coastal areas, overpumping has allowed seawater to intrude into aquifers, rendering groundwater unusable for generations. In inland agricultural regions, falling water tables have triggered sinkholes, soil collapse, and the loss of fertile land.

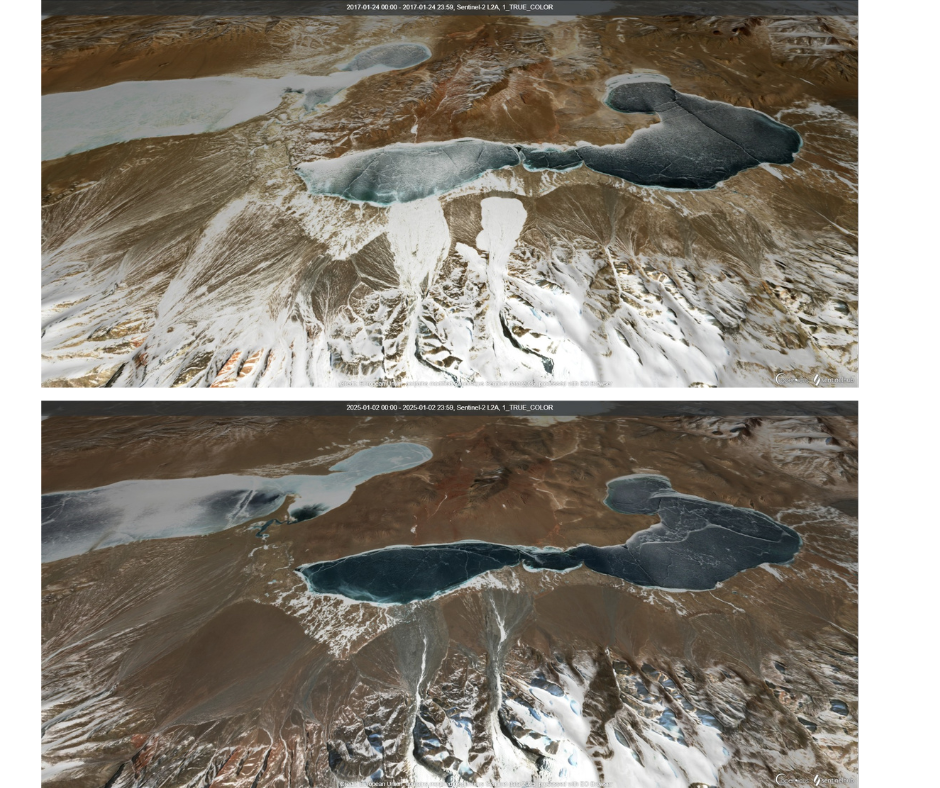

These satellite images show a dramatic impact of the Aru glacier collapses in western Tibet. First image was taken in 2017 and the second in 2025. Credit: UNU-INWEH

The cryosphere, glaciers and snowpacks that act as natural water storage systems are also being rapidly liquidated. The world has already lost more than 30 percent of its glacier mass since 1970. Several low- and mid-latitude mountain ranges could lose functional glaciers within decades.

“The liquidation of this frozen savings account interacts with groundwater depletion and surface water over-allocation to lock many basins into a permanent worsening water deficit state,” says the report.

This loss, as per the report, threatens the long-term water security of hundreds of millions of people who depend on glacier- and snowmelt-fed rivers for drinking water, irrigation, and hydropower, particularly in Asia and the Andes.

Madani said the biggest failure was treating groundwater as an unlimited safety net instead of a strategic reserve.

He says that when surface water tightened, many systems defaulted to “drill deeper” without enforceable caps.

“Authorities often recognize the consequences when it is already late, and meaningful action then faces major political barriers. For example, reducing groundwater use in farming can trigger unemployment, food insecurity, and even instability unless farmers are supported through short-term compensation and a longer-term transition to alternative livelihoods,” he added.

According to Madani, that kind of transition cannot be implemented overnight.

“So, business as usual continues. The result is predictable: groundwater gets “liquidated” to postpone hard choices, and by the time the damage is obvious, recovery is no longer realistic,” he told IPS news.

Agriculture Lies at the Heart of the Crisis

According to the report, farming accounts for approximately 70 percent of global freshwater withdrawals. About 3 billion people and more than half of the world’s food production are located in regions where total water storage is already declining or unstable.

The report states that more than 170 million hectares of irrigated cropland are under high or very high water stress. Land and soil degradation are making matters worse by reducing the ability of soils to retain moisture. The degradation of more than half of the global agricultural land is now moderate or severe.

Drought, once considered a natural hazard, is increasingly driven by human activity. Overallocation, groundwater depletion, deforestation, land degradation, and climate change have turned drought into a chronic condition in many regions.

“Drought-related damages, intensified by land degradation, groundwater depletion and climate change rather than rainfall deficits alone, already amount to about 307 billion US dollars per year worldwide,” the report states.

Water quality degradation further shrinks the usable resource base. Pollution from untreated wastewater, agricultural runoff, industrial effluents, and salinization means that even where water volumes appear stable, much of that water is unsafe or too costly to treat.

The report adds that the planetary freshwater boundary has already been crossed. Both blue water, surface and groundwater, and green water, soil moisture, have been pushed beyond a safe operating space.

Current governance systems, the authors argue, are not fit for this reality. Many legal water rights and development promises far exceed degraded hydrological capacity. Existing global agendas, focused largely on drinking water access, sanitation, and incremental efficiency gains, are inadequate for managing irreversible loss.

“Water bankruptcy must be recognized as a distinct post-crisis state, where accumulated damage and overshoot have undermined the system’s capacity to recover,” the report says.

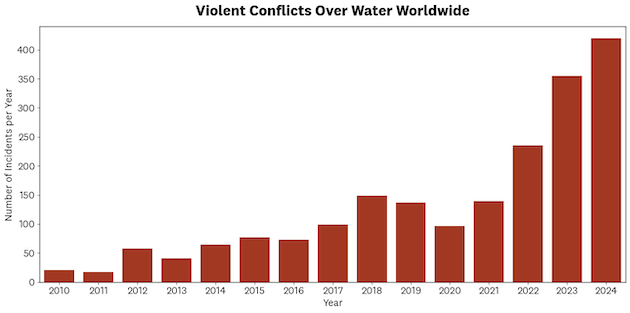

Water bankruptcy could result in a further increase in conflicts. Credit: UNU-INWEH

It warns that the implications of water bankruptcy are dire.

UN Under-Secretary-General Tshilidzi Marwala, Rector of UNU explains, “Water bankruptcy is becoming a driver of fragility, displacement, and conflict. Managing it fairly—ensuring that vulnerable communities are protected and that unavoidable losses are shared equitably—is now central to maintaining peace, stability, and social cohesion.”

Policy Implications

Instead of crisis management aimed at restoring the past, the report actually pitches for bankruptcy management. That means acknowledging insolvency, accepting irreversibility, and restructuring water use, rights, and institutions to prevent further damage.

The authors lay stress on the fact that water bankruptcy is also a justice and security issue. The costs of overshoot fall disproportionately on small farmers, rural communities, women, Indigenous peoples, and downstream users, while benefits have often accrued to more powerful actors.

“How societies manage water bankruptcy will shape social cohesion, political stability, and peace,” the report warns.

Furthermore, it urges governments and international institutions to use upcoming UN Water Conferences in 2026 and 2028 as milestones to reset the global water agenda, calling for water to be treated as an upstream sector central to climate action, biodiversity protection, food security, and peace.

“This is about a crisis that might arrive in the future. The world is already living beyond its hydrological means,” reads the report.

When asked why the report frames water bankruptcy as a justice and security issue and how governments can implement painful demand reductions without triggering social unrest or conflict, Madani said the demand reduction becomes dangerous when it is treated as a technical exercise instead of a political economy reform. In many water-bankrupt regions, according to him, water is effectively a jobs policy: it keeps low-productivity farming and local economies afloat.

“If you cut water without an economic transition, you create unemployment, food insecurity, and unrest. So the practical pathway is to decouple livelihoods and growth from water consumption. In many economies, water and other natural resources are used to keep low-efficiency systems alive. In most places, it is possible to produce more strategic food with less water and less land, and with fewer farmers—provided that farmers are supported through a transition and offered alternative livelihoods.”

According to Madani, governments should protect basic needs but target the big reductions where most water is used, especially agriculture and besides that, pair caps with a just transition package for farmers—compensation, insurance, buy-down or retirement of water entitlements where relevant, and real income alternatives.

He further suggests that the governments should invest in diversification, including services, industry, value-added agri-processing, and urban jobs, so communities can earn a living without expanding water withdrawals.

“In short, you avoid conflict by making demand reduction part of a broader economic transition, not a standalone water policy.”

IPS UN Bureau Report