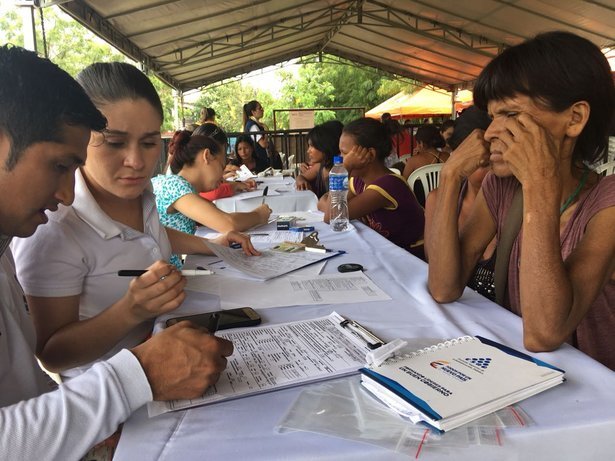

Civil Society, Cooperatives, Development & Aid, Economy & Trade, Editors’ Choice, Featured, Food and Agriculture, Gender, Headlines, Human Rights, Indigenous Rights, Latin America & the Caribbean, Poverty & SDGs, Regional Categories, TerraViva United Nations, Women & Climate Change, Women & Economy

Every other Tuesday, a working group of Mayan women meets to review the organization and progress of their food saving and production project in Uayma, in the state of Yucatán in southeastern Mexico. CREDIT: Courtesy of the Ko’ox Tani Foundation

– Every other Tuesday at 5:00 p.m. sharp, a group of 26 Mexican women meet for an hour to discuss the progress of their work and immediate tasks. Anyone who arrives late must pay a fine of about 25 cents on the dollar.

The collective has organized in the municipality of Uayma (which means “Not here” in the Mayan language) to learn agroecological practices, as well as how to save money and produce food for family consumption and the sale of surpluses.

“We have to be responsible. With savings we can do a little more,” María Petul, a married Mayan indigenous mother of two and a member of the group “Lool beh” (“Flower of the road” in Mayan), told IPS in this municipality of just over 4,000 inhabitants, 1,470 kilometers southeast of Mexico City in the state of Yucatán, on the Yucatán peninsula.

The home garden “gives me enough to eat and sell, it helps me out,” said Petul as she walked through her small garden where she grows habanero peppers (Capsicum chinense, traditional in the area), radishes and tomatoes, surrounded by a few trees, including a banana tree whose fruit will ripen in a few weeks and some chickens that roam around the earthen courtyard.

The face of Norma Tzuc, who is also married with two daughters, lights up with enthusiasm when she talks about the project. “I am very happy. We now have an income. It’s exciting to be able to help my family. Other groups already have experience and tell us about what they’ve been doing,” Tzuc told IPS.

The two women and the rest of their companions, whose mother tongue is Mayan, participate in the project “Women saving to address climate change”, run by the non-governmental Ko’ox Tani Foundation (“Let’s Go Ahead”, in Mayan), dedicated to community development and social inclusion, based in Merida, the state capital.

This phase of the project is endowed with some 100,000 dollars from the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (CEC), the non-binding environmental arm of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), formed in 1994 by Canada, the United States and Mexico and replaced in 2020 by another trilateral agreement.

The initiative got off the ground in February and will last two years, with the aim of training some 250 people living in extreme poverty, mostly women, in six locations in the state of Yucatán.

The maximum savings for each woman in the group is about 12 dollars every two weeks and the minimum is 2.50 dollars, and they can withdraw the accumulated savings to invest in inputs or animals, or for emergencies, with the agreement of the group. Through the project, the women will receive seeds, agricultural inputs and poultry, so that they can install vegetable gardens and chicken coops on their land.

The women write down the quotas in a white notebook and deposit the savings in a gray box, kept in the house of the group’s president.

José Torre, project director of the Ko’ox Tani Foundation, explained that the main areas of entrepreneurship are: community development, food security, livelihoods and human development.

“What we have seen over time is that the savings meetings become a space for human development, in which they find support and solidarity from their peers, make friends and build trust,” he told IPS during a tour of the homes of some of the savings group participants in Uayma.

The basis for the new initiative in this locality is a similar program implemented between 2018 and 2021 in other Yucatecan municipalities, in which the organization worked with 1400 families.

María Petul, a Mayan indigenous woman, plants chili peppers, tomatoes, radishes and medicinal herbs in the vegetable garden in the courtyard of her home in Uayma, in the southeastern Mexican state of Yucatán. CREDIT: Emilio Godoy/IPS

Unequal oasis

Yucatan, a region home to 2.28 million people, suffers from a high degree of social backwardness, with 34 percent of the population living in moderate poverty, 33 percent suffering unmet needs, 5.5 percent experiencing income vulnerability and almost seven percent living in extreme poverty.

The COVID-19 pandemic that hit this Latin American country in February 2020 exacerbated these conditions in a state that depends on agriculture, tourism and services, similar to the other two states that make up the Yucatán Peninsula: Campeche and Quintana Roo.

Inequality is also a huge problem in the state, although the Gini Index dropped from 0.51 in 2014 to 0.45, according to a 2018 government report, based on data from 2016 (the latest year available). The Gini coefficient, where 1 indicates the maximum inequality and 0 the greatest equality, is used to calculate income inequality.

The situation of indigenous women is worse, as they face marginalization, discrimination, violence, land dispossession and lack of access to public services.

More than one million indigenous people live in the state.

Women participating in a project funded by the North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation record their savings in a white notebook and deposit them in a gray box. Mayan indigenous woman Norma Tzuc belongs to a group taking part in the initiative in Uayma, in the southeastern Mexican state of Yucatán. CREDIT: Emilio Godoy/IPS

Climate crisis, yet another vulnerability

Itza Castañeda, director of equity at the non-governmental World Resources Institute (WRI), highlights the persistence of structural inequalities in the peninsula that exacerbate the effects of the climate crisis.

“In the three states there is greater inequality between men and women. This stands in the way of women’s participation and decision-making. Furthermore, the existing evidence shows that there are groups in conditions of greater vulnerability to climate impacts,” she told IPS from the city of Tepoztlán, near Mexico City.

She added that “climate change accentuates existing inequalities, but a differentiated impact assessment is lacking.”

Official data indicate that there are almost 17 million indigenous people in Mexico, representing 13 percent of the total population, of which six million are women.

Of indigenous households, almost a quarter are headed by women, while 65 percent of indigenous girls and women aged 12 and over perform unpaid work compared to 35 percent of indigenous men – a sign of the inequality in the system of domestic and care work.

To add to their hardships, the Yucatan region is highly vulnerable to the effects of the climate crisis, such as droughts, devastating storms and rising sea levels. In June 2021, tropical storm Cristobal caused the flooding of Uayma, where three women’s groups are operating under the savings system.

For that reason, the project includes a risk management and hurricane early warning system.

The Mexican government is building a National Care System, but the involvement of indigenous women and the benefits for them are still unclear.

Petul looks excitedly at the crops planted on her land and dreams of a larger garden, with more plants and more chickens roaming around, and perhaps a pig to be fattened. She also thinks about the possibility of emulating women from previous groups who have set up small stores with their savings.

“They will lay eggs and we can eat them or sell them. With the savings we can also buy roosters, in the market chicks are expensive,” said Petul, brimming with hope, who in addition to taking care of her home and family sells vegetables.

Her neighbor Tzuc, who until now has been a homemaker, said that the women in her group have to take into account the effects of climate change. “It has been very hot, hotter than before, and there is drought. Fortunately, we have water, but we have to take care of it,” she said.

For his part, Torre underscored the results of the savings groups. The women “left extreme poverty behind. The pandemic hit hard, because there were families who had businesses and stopped selling. The organization gave them resilience,” he said.

In addition, a major achievement is that the households that have already completed the project continue to save, regularly attend meetings and have kept producing food.