Civil Society, Development & Aid, Economy & Trade, Editors’ Choice, Featured, Headlines, Human Rights, Labour, Latin America & the Caribbean, Regional Categories, Sustainable Development Goals, TerraViva United Nations, Women & Economy

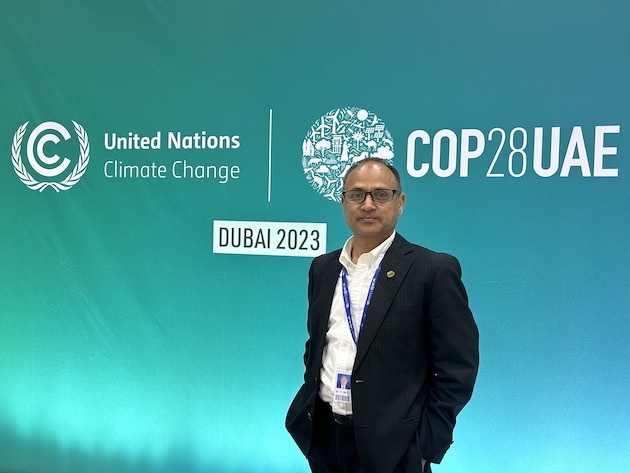

On International Women’s Day on Mar. 8, thousands of Chilean women of all ages took to Santiago’s central Alameda avenue to demonstrate peacefully for several hours and turn the Chilean capital into a stage for protest and demands for their rights. Some of them were women caregivers accompanied by dependent women. CREDIT: Orlando Milesi / IPS

– In Chile, as in the rest of Latin America, the task of caring for people with disabilities, the elderly and children falls to women who, as a result, do not have access to paid jobs or time for themselves.

Unpaid domestic and care work is crucial to the economies of the region, accounting for around 20 percent of gross domestic product (GDP).

Measurements by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) found that in 16 Latin American countries, women spend between 22.1 and 42.8 hours per week on unpaid domestic and care work. Men only spend between 6.7 and 19.8 hours.

Ana Güezmes, director of ECLAC’s Division for Gender Affairs, told IPS that “in most countries women work longer total hours, but with a lower proportion of paid hours.”

“This work, which is fundamental for sustaining life and social well-being, is disproportionately assigned to women. This situation impacts women’s autonomy, economic opportunities, labor and political participation and their access to leisure activities and rest,” Güezmes said at ECLAC headquarters in Santiago.

The situation is far from changing as it is replicated in young women who devote up to 20 percent of their time to unpaid work.

Paloma Olivares, president for Santiago of the women’s organization Yo Cuido, works in her office in the working-class municipality of Estación Central, in the northeast of the Chilean capital. CREDIT: Orlando Milesi / IPS

Women left on their own as caregivers

Paloma Olivares, 43, chairs the Yo Cuido Association in Santiago, Chile, which brings together 120 members, only two of them men.

“Women caregivers are denied the right to participate on equal terms in society because we are forced to choose between exercising our rights or doing caregiving work. And we cannot choose because it is a job we do for a loved one, for a family member.” — Paloma Olivares

“Women caregivers are denied the right to participate on equal terms in society because we are forced to choose between exercising our rights or doing caregiving work. And we cannot choose because it is a job we do for a loved one, for a family member,” she told IPS.

“We are left in a position of inequality, of absolute vulnerability because you have to devote your life to supporting someone else at the expense of your personal life,” she said.

Olivares stopped working to care for Pascale, her granddaughter, who was born with cerebral palsy and hydrocephalus.

Three days after her birth, a bacterium became lodged in her central nervous system. She was hospitalized for almost a year and became severely dependent.

At the time, she was given a seven percent chance of survival. Today she is eight years old, goes to school and lives an almost normal life thanks to the work of her caregivers.

She is now cared for by her mother Valentina, who had her at the age of 15. Paloma was able to return to paid work, but her daughter abandoned her studies to take care of Pascale.

“When you start being a caregiver, friendships end, because no one can keep up. Even the family drifts away. That’s why most caregiving families are single-parent, the woman is left alone to care because the man can’t keep up with the pace and the emotional and economic burden,” she said.

Olivares participated from Mar. 12 to 14 in a public hearing, digital and in person, on the right to care and its interrelation with other rights, in a collective request of several social organizations and the governments of Chile and other Latin American countries before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR Court), based in San Jose, Costa Rica,

In the request for an opinion from the IACHR Court, “we asked the Court to take a stance on the right to care and how the rights of women in particular have been violated because there are no public policies in this regard. We want the Court to pronounce itself on the right to care and how the States should address it so that this right is guaranteed and so the rights of caregivers are no longer violated,” she explained.

It is expected that the Court’s pronouncement on the matter will come out in April and could establish minimum parameters regarding women caregivers for Chile and other Latin American countries.

Critical situation for women caregivers

Millaray Sáez, 59, told IPS by telephone from the southern Chilean city of Concepción that her son Mario Ignacio, 33, “is no longer the autonomous person he was. Since 2012 he has become a baby.”

She chairs the AML Bío Bío Corporación, an association of women in the Bío Bío region created in 2017 to address the question of female empowerment and today dedicated to the issue of caregivers.

“I have been a caregiver for 30 years for my son who has refractory epilepsy. He became prostrate in 2012 as a result of medical negligence,” said the international trade engineer who has become an expert in public policies on care with a gender perspective.

Sáez said “the situation of women caregivers is very bad, very precarious. There is a single cause, which is the work of caregiving, but the consequences are multidimensional…. from physical deterioration to the lack of legislation to protect against forms of violence, and ranging from the family to what society or the State adds.”

She also pointed to the economic consequences of dependent care.

She cited cases in which caregivers spend over 150 dollars a month on diapers alone for a person who needs them. And she pointed out that the government provides an economic aid stipend of just 33 dollars a month.

Teresa Valdés, head of the Gender and Equity Observatory of the Catholic University of Chile, praises the new registry of caregivers promoted by the Chilean government, but underlines the importance of municipal experiences and initiatives that promote homes and care centers to facilitate the lives of women caregivers. CREDIT: Orlando Milesi / IPS

The magnitude of the problem

It is a pending task to determine the number of women caregivers in Chile.

The government of leftist President Gabriel Boric created a system for caregivers to register and receive a credential that gives them access to public services.

“The credential is the gateway to the Chile Cuida System. With it we seek to make them visible in services and institutions and to reward them for their work by saving them waiting time in daily procedures,” the Minister of Women and Gender Equity, Antonia Orellana, explained to IPS.

So far, there are 85,817 people registered, of whom 74,650 are women, or 87 percent of the total, and 11,167 are men, according to data provided to IPS on Mar. 14 by the Undersecretariat of Social Services of the Ministry of Social Development and Family.

But Chile has 19.5 million inhabitants, and “17.6 percent of the adult population has some degree of disability and, therefore, requires the daily care and support of other people in the home,” the minister said.

That means 3.4 million Chileans depend on a caregiver.

According to Orellana, facing the care scenario projected by the aging of the population will require the collaboration of everyone to “create and sustain an economic and productive system that generates decent work and formal employment, leaving no one behind.”

Other urgent demands by women

Sociologist Teresa Valdés, head of the Gender and Equity Observatory, told IPS that there are many social problems facing Chilean women today, “especially those related to access to health care, social security, unequal pay and access to different goods and services.”

Valdés regretted that the term “women caregivers” is used to refer to the role that women play and the tasks that are culturally assigned to them as a priority.

“We are all caregivers, all women work double shifts. The time-use survey shows that we work an additional 41 hours per week of so-called unpaid reproductive care work,” she said.

According to Valdés, the main advance in this problem is to include it in the debate because these are policies that require a lot of resources and extensive development, since they have to do with the structure of the labor market.

“Part of the proposal should be how to ‘de-genderize’, how care becomes a task of shared responsibility and not only that women have more time to take on the care tasks,” she said.

“When we call women caregivers, we are referring to the group most affected by the conditions of sexual division of labor and family reproduction,” she added.

The expert proposes progressively identifying ways to support women caregivers in order to provide them with available time and take care of their mental health.

She praised the programs promoted by some municipalities to free up time for these women to enjoy leisure and self-care.

“We have to move towards a cultural conception that we are all dependent. Today I depend on you, tomorrow you depend on me. Care is a social task in which I take care of you today so that you can take care of me tomorrow. And that is something that has to start from the earliest childhood,” she argued.