…..Projects at various stages of being completion we are hardly unveiled to the public not because they were ready for use but because the political moment demanded visibility…..

According to local media, the period leading up to national elections in Malawi has increasingly blurred the line between genuine development work and political performance.

Public infrastructure, instead of following disciplined technical schedules, has often been pulled into the orbit of campaign strategy.

Projects at various stages of incompletion have been hurriedly unveiled to the public, not because they were ready for use, but because the political moment demanded visibility.

In many instances, several projects were “officially opened” within a single day, creating an impression of extraordinary productivity.

What mattered most in these moments was not whether a road was durable, a school functional, or a health centre fully equipped.

What mattered was the image of action.

Commissioning ceremonies became tools of persuasion, designed to signal delivery rather than demonstrate lasting value.

The assumption underpinning this approach was that voters respond more readily to what they can see than to what they can sustainably use.

Yet beneath the spectacle lies a series of consequences that only surface long after election posters have come down.

Projects launched before completion are often victims of rushed execution.

Design elements are simplified, timelines compressed, and quality assurance postponed or ignored altogether.

Contractors operating under political pressure may prioritize speed over standards, knowing that the most critical inspection is not technical, but ceremonial.

Engineers and oversight institutions, constrained by directives from above, may find themselves endorsing stages of work that would normally require further testing.

On commissioning day, the structures may look complete.

Within months, cracks appear, systems malfunction, and users begin to experience the real cost of premature celebration.

Maintenance budgets are strained earlier than planned.

The useful life of infrastructure assets is reduced without ever being openly acknowledged.

In extreme cases, rehabilitation becomes unavoidable, effectively turning one project into two expenditures.

This culture also reshapes how public money is allocated.

Resources are diverted from essential but invisible components such as drainage systems, safety installations, and long-term maintenance frameworks.

Instead, funds flow toward elements that make a project look complete enough for a public launch.

Projects that cannot be easily showcased are postponed or quietly deprioritized.

Development planning loses its coherence, becoming responsive to political timelines rather than technical logic or national need.

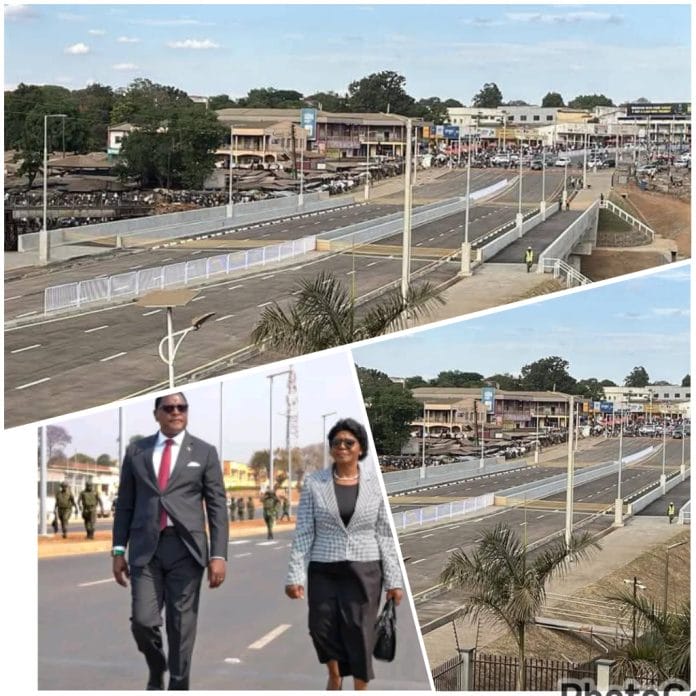

Within this environment, the five-lane K57 billion Lilongwe bridge presents a striking contrast.

Unlike many smaller projects, it resisted being pulled into the rhythm of campaign-driven commissioning.

Its sheer size and engineering complexity made symbolic completion impractical.

A bridge of that scale cannot be half-finished without creating obvious and dangerous risks.

Structural integrity, load-bearing capacity, and system integration are not features that can be convincingly staged.

In this case, engineering realities set firm limits on political manoeuvring.

The project also attracted intense scrutiny from professionals, the media, and the wider public.

Any attempt to rush or misrepresent its readiness would have been immediately exposed.

The political consequences of failure would have been severe, both in terms of safety and credibility.

As a result, the space for theatrics was significantly reduced.

This contrast exposes a deeper truth about governance and infrastructure delivery.

Where institutions are fragile and projects are modest or scattered, political influence can easily override technical judgment.

Where projects are large, complex, and highly visible, professional standards and public attention can act as a substitute for formal accountability.

The broader habit of favouring appearance over substance carries long-term political risks.

While frequent project launches may initially impress, repeated encounters with incomplete or failing infrastructure erode public trust.

Citizens become sceptical of official announcements and cynical about government promises.

For civil servants and technical professionals, this environment is deeply discouraging.

Expertise is sidelined in favour of performance.

Long-term planning is sacrificed to short-term political gain.

From an economic perspective, the costs are substantial.

Rushed construction, frequent variations, and post-election repairs inflate overall expenditure.

Development partners and investors observe these patterns closely.

Political interference is factored into risk assessments, often translating into higher costs or reduced confidence.

The lesson from the Lilongwe bridge is therefore not simply about one project that avoided premature celebration.

It is a reminder that meaningful development requires protection from electoral pressures.

Until infrastructure delivery is insulated from campaign imperatives, quality will remain negotiable.

And until that separation is achieved, Malawians will continue to pay more for projects that deliver less.

In the end, progress is not measured by the number of ceremonies held before an election.

It is measured by whether infrastructure still serves its purpose long after the votes have been counted.

Discover more from The Maravi Post

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.