Civil Society, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Featured, Global, Global Governance, Headlines, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, Poverty & SDGs, TerraViva United Nations

– The world saw more new confirmed COVID-19 cases last week than any week to date. And as the pandemic grows, its epicenter is moving from advanced economies to more developing countries, including Brazil, India, and South Africa.

How is the pandemic likely to evolve as it spreads to poorer countries?

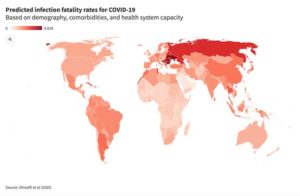

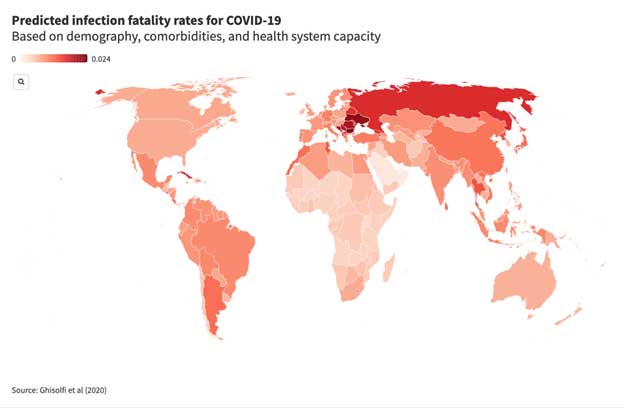

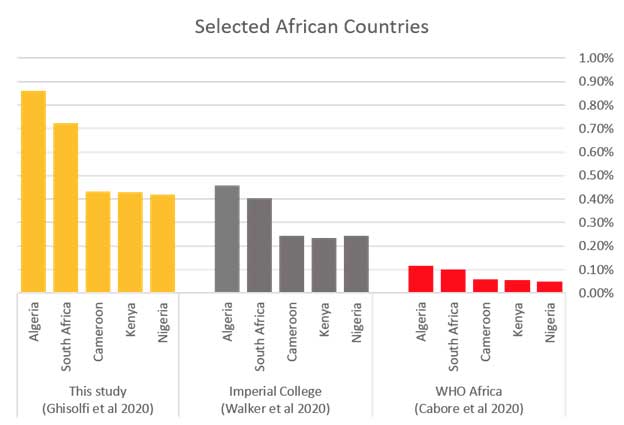

In a new working paper, we attempt to answer one piece of that question, predicting the infection fatality rate, or IFR, for COVID-19 for 187 countries based on demography, comorbidities, and the strength of health systems.

The IFR numbers we report are somewhat higher—sometimes dramatically so—than the figures given for many developing countries in earlier influential studies, including the Imperial College team’s scenarios for the global pandemic and a recent report by the WHO Africa bureau.

That difference can be chalked up to how we incorporate two factors: pre-existing health conditions, and the relative strength of health systems.

For many developing countries, comorbidities partially offset the advantages of youth

A recent study in Science by Salje et al., for instance, finds that with French-level healthcare, the probability of dying with COVID-19 rises roughly eight-fold when moving from the 60-69 age group to the 70 and above range. This is good news for developing countries, which generally have a much younger population than France.

Most previous forecasts of the COVID-19 infection fatality rate have incorporated this demographic advantage. However, they have generally not included the offsetting effect of cross-country differences in comorbidities.

Those comorbidities—such as diabetes, hypertension, and ischemic cardiovascular diseases— matter a lot. Data from Italy show that roughly 96 percent of COVID-19 fatalities report one or more relevant comorbidities.

Inverting that probability using Bayes’ rule and data on France’s IFR and comorbidity distribution, we find that the probability of dying from a COVID-19 infection for patients under 40 is roughly 134-times higher with a relevant comorbidity than without.

Developing countries generally have lower rates of relevant comorbidities compared to high-income countries (where the best measures of infection fatality rates come from). But whereas comorbidities are concentrated among the elderly in rich countries, some developing countries—such as South Africa—report a considerably higher share of these conditions among middle-aged people.

Future work would benefit from more careful treatment of comorbidities like HIV/AIDS that have higher prevalence in lower-income countries. But even a simple adjustment for comorbidities partially undermines many developing countries’ demographic advantages.

Evidence from other viral respiratory infections suggests a much bleaker scenario for COVID-19 in the developing world

So far, our estimates assume that an individual infected with COVID-19 in, say, Uganda has the same probability of dying as someone with the same sex, age, and number of comorbidities in France. Clearly that’s optimistic, given the overall capacity of Uganda’s health system relative to France’s. But exactly how optimistic?

To gauge how much fatality rates might vary with health system capacity, we draw on estimates of the infection fatality rate for another viral respiratory infection, namely influenza. We focus on children under five years old, to purge variation in age and comorbidities that typically begin later in life, and scale the odds ratio of dying from COVID-19 by the ratio of child influenza death rates across countries by income group.

Adjusting for health-system capacity in this way yields COVID-19 infection fatality rates that are considerably higher than previous estimates for the developing world. For the five countries in Sub-Saharan Africa with the largest confirmed COVID-19 epidemics to date, our results are roughly twice as high as those from Imperial College, which does not factor in comorbidities or health system strength beyond a simple capacity constraint on hospital beds.

And they are roughly eight times higher than forecasts from the WHO Africa, which do not adjust for health system capacity and only scale the IFR downward (never upward) due to comorbidities.

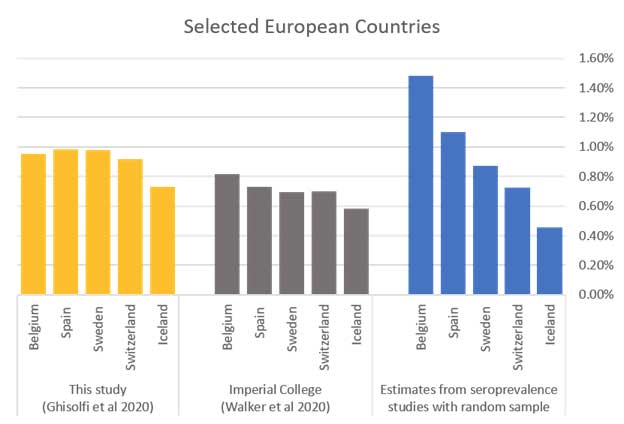

Comparing predicted COVID-19 infection fatality rates across studies

Our results are more in line with the Imperial College predictions for Europe, as shown in the bottom panel above. For the five European countries shown, we can also compare to a more “gold standard” benchmark, i.e., infection fatality rates calculated on the basis of seroprevalence studies of a random sample of the population (blue bars).

Both our results and the Imperial college results match these seroprevalence studies fairly well on average, but fail to explain much of the intra-European variance (some of which may be due to variance in how deaths are counted, e.g., Belgium’s fairly liberal definition of a COVID-19 death to include all unexplained nursing home deaths).

In short, our IFR estimates seem fairly plausible for Europe, where we have an independent reference point, and our results suggest that earlier predictions for developing countries that ignore health system capacity may be far too optimistic.

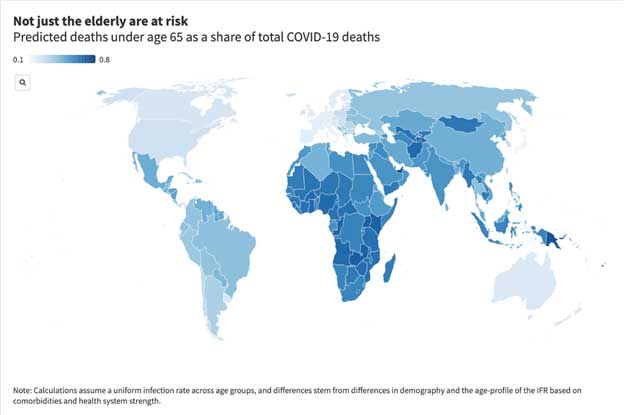

In line with recent news reports, it’s likely young people will make up a larger share of COVID-19 deaths in the developing world

In the United States to date, patients over 75 years old represent over 60 percent of COVID-19 deaths. In Italy, the number of fatalities above 70 is 85 percent.

Both demography and weak health systems explain why COVID-19 deaths are more concentrated among younger people in the developing world

Although predicted IFRs display a steep age gradient in all contexts, due to demographic differences the bulk of deaths in low- and lower-middle income countries is predicted to come from middle-aged patients (40-70).

Less obviously, differences in health system capacity are also likely to flatten the age gradient of COVID-19 deaths in developing countries. In Europe, data is consistent with the hypothesis that intensive care saves the lives of a higher proportion of young than elderly COVID-19 patients. Thus, when high-quality intensive care is lacking, the advantages of youth are more muted.

These estimates are far from the final word on this question. But we hope that our calculations provide an important cautionary note about developing countries’ demographic advantages in facing down COVID-19.

Planning for the ongoing pandemic response and calibration of containment policies should factor in the wide variation in predicted IFRs across contexts. Specifically, policymakers in low-income countries should be cognizant that any demographic advantages with respect to COVID-19 fatality rates are likely to be partially offset by disadvantages in terms of the age-distribution of comorbidities, and even more so by gaps in health system capacity.

*Justin Sandefur is a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development (CGD) ; Selene Ghisolfi is an economics post-doc at the Laboratory for Effective Anti-poverty Policies Bocconi, and a PhD student at the Institute for International Economic Studies, Stockholm University; Ingvild Almås is a professor of economics at the Institute for International Economic Studies, Stockholm University; Tillmann von Carnap is a PhD student at the Institute for International Economic Studies, Stockholm University; Jesse Heitner is a health economist at Aceso Global; and Tessa Bold is an associate professor at the Institute for International Economic Studies, Stockholm University.