The State of Civil Society report from CIVICUS, the global civil society alliance which was officially launched on March 30, 2023, exposes the gross violations of civic space. Credit CIVICUS

By Joyce Chimbi

NAIROBI, Mar 31 2023 (IPS)

As conflict and crises escalate to create human emergencies that have displaced over 100 million people worldwide, civil society’s vital role of advocating for victims and monitoring human rights cannot be over-emphasised.

The 2022 Nobel Peace Prize award to activists and organisations in Belarus, Russia and Ukraine for working to uphold human rights in the thick of conflict underpins this role.

Yet this has not stopped gross violations of civic space as exposed by the State of Civil Society report from CIVICUS, the global civil society alliance, which was officially launched on March 30, 2023.

“This year’s report is the 12th in its annual published series, and it is a critical look back on 2022. Exploring trends in civil society action, at every level and in every arena, from struggles for democracy, inclusion, and climate justice to demands for global governance reform,” said Ines Pousadela from CIVICUS.

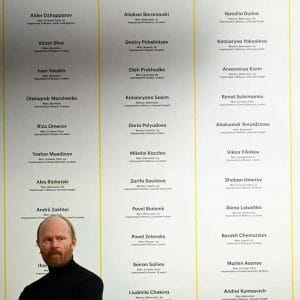

The report particularly highlights the many ways civil society comes under attack, caught in the crossfire and or deliberately targeted. For instance, the Russian award winner, the human rights organisation Memorial, was ordered to close in the run-up to the war. The laureate from Belarus, Ales Bialiatski, received a 10-year jail sentence.

Mandeep Tiwana stressed that the repression of civic voices and actions is far from unique. In Ethiopia, “activists have been detained by the state. In Mali, the ruling military junta has banned activities of CSOs that receive funding from France, hampering humanitarian support to those affected by conflict. In Italy, civil society groups face trial for rescuing migrants at sea.”

Ines Pousadela at the launch of the CIVICUS State of Civil Society Report. Credit: Joyce Chimbi/IPS

Spanning over six chapters titled responding to conflict and crisis, mobilising for economic justice, defending democracy, advancing women’s and LGBTQI+ rights, sounding the alarm on the climate emergency and urging global governance reform, the analysis presented by the report draws from an ongoing analysis initiative, CIVICUS Lens.

On responding to conflict and crisis, Oleksandra Matviichuk from the Center for Civil Liberties in Ukraine spoke about the Russian invasion and the subsequent “unprecedented levels of war crimes against civilians such as torture and rape. And, a lack of accountability despite documented evidence of crimes against civilians.”

Bhavani Fonseka, from the Centre for Policy Alternatives, Sri Lanka, addressed the issue of mobilising for economic justice and how Sri Lanka captured the world’s attention one year ago through protests that start small in neighbourhoods and ultimately led to the President fleeing the country.

Launched in January 2022, CIVICUS Lens is directly informed by the voices of civil society affected by and responding to the major issues and challenges of the day.

Through this lens, a civil society perspective of the world as it stands in early 2023 has emerged: one plagued by conflict and crises, including democratic values and institutions, but in which civil society continues to strive to make a crucial difference in people’s lives.

On defending democracy, Amine Ghali of the Al Kawakibi Democracy Transition Center in Tunisia spoke about the challenge of removing authoritarian regimes, making significant progress in levels of democracy only for the country to regress to authoritarianism.

“It starts with the narrative that democracy is not delivering; let me have all the power so that I can deliver for you. But they do not deliver. All they do is consolidate power. A government with democratic legitimacy demolishing democracy is where we are in Tunisia,” he said.

Erika Venadero from the National Network of Diverse Youth, Mexico, spoke about the country’s journey that started in the 1960s towards egalitarian marriages. Today, same-sex marriages are provided for in the law.

On global governance reforms, Ben Donaldson from UNA-UK spoke about global governance institutional failure and the need to improve what is working and reform what is not, with a special focus on the UN Security Council.

“It is useful to talk about Ukraine and the shortcomings of the UN Security Council. A member of the UN State Council is unable to hold one of its members accountable. There are, therefore, tensions at the heart of the UN. The President of Ukraine and many others ask, what is the UN for if it cannot stop the Ukraine invasion?”

Baraka, a youthful climate activist and sustainability consultant in Uganda, spoke about ongoing efforts to stop a planned major pipeline project which will exacerbate the ongoing climate crisis, affecting lives and livelihoods.

His concerns and actions are in line with the report findings that “civil society continues to be the force sounding the alarm on the triple threat of climate change, pollution and biodiversity loss. Urging action using every tactic available, from street protest and direct action to litigation and advocacy in national and global arenas.”

But in the context of pressures on civic space and huge challenges, the report further finds that “civil society is growing, diversifying and widening its repertoire of tactics.”

Moving forward, the report highlights 10 ideas, including an urgent need for a broad-based campaign to win recognition of civil society’s vital role in conflict and crisis response as well as greater emphasis by civil society and supportive states on protecting freedom of peaceful assembly.

Additionally, the need for civil society to work with supportive states to take forward plans for UN Security Council reform and proposals to open up the UN and other international institutions to much greater public participation and scrutiny.

In all, strengthening and enhancing the membership and reach of transnational civil society networks to enable the rapid deployment of solidarity and support when rights come under attack was also strongly encouraged.

IPS UN Bureau Report