Active Citizens, Civil Society, Climate Action, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Energy, Environment, Food and Agriculture, Headlines, Innovation, Integration and Development Brazilian-style, Latin America & the Caribbean, Projects, Regional Categories, Water & Sanitation

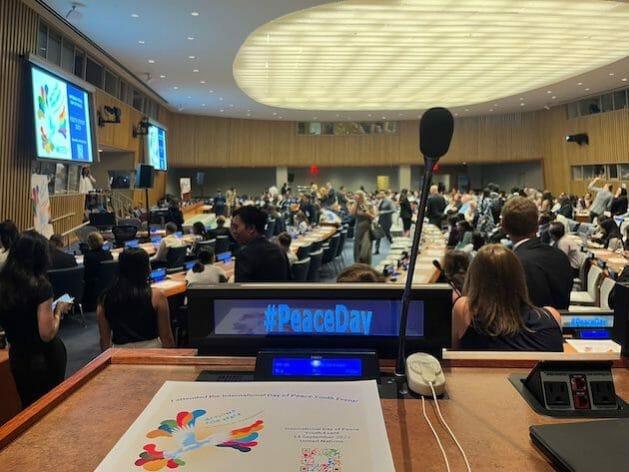

Artist and farmer Chavely Casimiro and her daughter Leah Amanda Díaz feed one of the biodigesters at Finca del Medio, a farm in central Cuba. The biodigester produces about seven meters of biogas per day, enough energy for cooking, baking and dehydrating food. CREDIT: Jorge Luis Baños / IPS

– Combining technologies and innovations to take advantage of solar, wind, hydro and biomass potential has made the Finca del Medio farm an example in Cuba in the use of clean energies, which are the basis of its agroecological and environmental sanitation practices.

Renewable energy sources are used in many everyday processes such as electricity generation, lighting, water supply, irrigation and water heating, as well as in cooking, dehydrating, drying, baking and refrigeration of foodstuffs.

“We started out with windmills on artesian wells and hydraulic rams to pump water. That gave us an awareness of the amount of energy we needed and of how to expand its use,” said farmer José Antonio Casimiro, 65, owner of this agroecological family farm located in the center of this long Caribbean island nation.

“More incentives, better policies and financial support are needed so that farming families have sufficient energy for their work and can improve the comfort of their homes and quality of life.” — José Antonio Casimiro

The farmer expressed his appreciation of the help of his son, 41, also named Antonio Casimiro, in the installation of the two mills at Finca del Medio, during the days in which IPS visited the farm and shared in activities with the family.

“There was no one to assemble or repair them. We both had to study a great deal, and we learned to do a lot of construction things as we went along and perfected the techniques,” said Casimiro junior, referring to the equipment that is now inactive, but is capable of extracting some 4,000 liters of water daily from the water table.

When rainfall is abundant and the volume of the 55,000-cubic-meter-capacity reservoir rises, the hydraulic ram comes to life. The device diverts about 20,000 liters of water to a 45,000-liter tank, 400 meters away and 18 meters above the level of the reservoir.

“The only energy the rams use is the water pressure itself. Placing it on the highest part of the land makes it easier to use the slope for gravity irrigation, or to fill the animals’ water troughs,” explained Chavely Casimiro, 28, the youngest daughter of José Antonio and Mileidy Rodríguez, also 65.

An artist who also inherited the family’s “farming gene”, Chavely highlighted some twenty innovations made by her father to the hydraulic ram, in order to optimize water collection.

Other inventions speed up the assembly and disassembly of the windmills for maintenance, or in the event of tropical cyclones.

“We have been replacing the water supply with solar panels, which are more efficient. They can be removed faster (than the windmill blades) if a hurricane is coming. You can incorporate batteries and store the energy,” said Casimiro.

“Let’s say a windmill costs about 2,000 dollars. With that amount you can buy four 350-watt panels. That would be more than a kilowatt hour (kWh) of power. You buy a couple of batteries for 250 dollars each, and with that amount of kWh you can pump the equivalent of the water of about 10 windmills,” he said.

But the farmer said the windmills are more important than the energy they generate. “It would be nice if every farm had at least one windmill. For me it is very symbolic to see them pumping up water,” he said.

Lorenzo Díaz, the husband of Chavely Casimiro, uses a solar oven to cook food. In the background can be seen a windmill and a solar heater, other technologies that take advantage of the potential for renewable energies on the Finca del Medio farm in central Cuba. CREDIT: Jorge Luis Baños / IPS

Innovations

Located in the municipality of Taguasco, in the central province of Sancti Spíritus, some 350 kilometers east of Havana, Finca del Medio follows a family farm model including permaculture, agroecology and agricultural production based on the use of clean energy.

In 1993, Casimiro and Rodríguez with their children Leidy and José Antonio – a year later, Chavely was born – decided to settle on the 13-hectare farm of their paternal grandparents, with the aim of reversing its deterioration and soil erosion and installing perimeter fences.

The erosion of the land was due to the fact that in the past the farm was dedicated to the cultivation of tobacco, which depleted the soil, and later it had fallen into abandonment, as well as the house.

The older daughter is the only one who does not live and work on the farm, although she does spend time there, and a total of ten family members live there, including four grandchildren. All the adults either work on the farm or help out with different tasks.

With the help of technological innovations adapted to the local ecosystem, and empirical and scientific knowledge, the family has become self-sufficient in rice, beans, tubers, vegetables, milk, eggs, honey, meat, fish and more than 30 varieties of fruit. The only basic foodstuffs not produced on the farm are sugar and salt.

They sell all surplus production, including cow’s milk, for which they have specific contracts, and they are also promoting agrotourism, for which they are making further improvements to the facilities.

At Finca del Medio, a system of channels and ditches allows the infiltration of rainwater, reduces erosion of the topsoil and conserves as much water as possible for subsequent irrigation.

These innovations also benefit neighboring communities by mitigating flooding and replenishing the water table, which has brought water back to formerly dry wells.

The construction of the house is also an offshoot of technological solutions to the scarcity of resources such as steel, which led to the design of dome-shaped roofs made of mud bricks and cement.

The design aids in rainwater harvesting, improves hurricane protection, and boosts ventilation, creating cooler spaces, which reduces the need for air conditioning equipment and bolsters savings.

Along with food production, the new generations and members of the Casimiro-Rodriguez family engage in educational activities to raise awareness about good agricultural and environmental practices.

Students from nearby schools come to the farm to learn about these practices, as well as specialists in agroecology and people from different parts of the world, interested in sharing the experience. Meanwhile, several members of the family have traveled abroad to give workshops on agroecology and permaculture.

Farmers José Antonio Casimiro (R) and his son of the same name talk in the mechanical workshop at their Finca del Medio farm. Both have come up with innovations for the use of windmills, the hydraulic ram and biodigesters, as well as agricultural tools. CREDIT: Jorge Luis Baños / IPS

Solar and biogas potential

On one of the side roofs of the house are 28 photovoltaic panels that provide about eight kWh, connected to batteries. The stored energy covers the household’s needs during power outages that affect the island due to fuel shortages and breakdowns and problems in maintenance of its aging thermoelectric plants.

In addition, the household has three solar water heaters with a capacity of 380 liters.

Next to the kitchen, two fixed-dome biodigesters produce another renewable fuel, biogas, composed mainly of methane and carbon dioxide from the anaerobic decomposition of animal manure, crop waste and “even sewage from the house, which we channel so that the waste does not contaminate the environment,” said Casimiro.

Due to the current shortage of manure as the number of cows has been reduced, only one of the biodigesters is now operational, producing about seven meters of biogas per day, sufficient for cooking, baking and dehydration of foodstuffs.

The innovative family devised a mechanism to extract – without emptying the pond of water or stopping biogas production – from the bottom the solids used as biofertilizers, as well as hundreds of liters of effluent for fertigation (a combination of organic fertilizers and water) of the crops, by gravity.

The installation of the biodigesters, the solar panels and one of the solar heaters was supported by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (Cosude) and the Indio Hatuey Experimental Station of Pastures and Forages through its Biomass-Cuba project, Casimiro said.

He also expressed gratitude for the link with other scientific institutions such as the Integrated Center for Appropriate Technologies, based in the central province of Camagüey, which is focused on offering solutions to the needs of water supply and environmental sanitation, and played an essential role in the installation of the hydraulic ram.

The farmer said the farm produces the equivalent of about 20 kWh from the combination of renewable energies, and if only conventional electricity were used, the cost would be around 83 dollars a month.

Lorenzo Díaz feeds firewood into an innovative stove that allows the Finca del Medio farm to efficiently cook food, dehydrate or dry fruits and spices, heat water and preserve meat, among other functions. CREDIT: Jorge Luis Baños / IPS

Efficient stove

In the large, functional kitchen, the stove covered with white tiles and a chimney has been remodeled 16 times to make it more efficient and turn it into another source of pride at the farm.

Fueled by firewood, coconut shells and other waste, “the stove makes it possible to cook food, dehydrate fruits and spices, heat water and preserve meat, among other tasks,” Rodríguez told IPS as she listed some of the advantages of this other offshoot of the family’s ingenuity that helps her as a skilled cook and pastry chef.

She pointed out that by extracting all the smoke, “the design makes better use of the heat, which will be used in a sauna” being built next to the kitchen, for the enjoyment of the family and potential tourists.

Casimiro is in favor of incorporating clean energy into agricultural processes, but he said that “more incentives, better policies and financial support are needed so that farming families have sufficient energy for their work and can improve the comfort of their homes and quality of life.”

Since 2014, Cuba has had a policy for the development of renewable energy sources and their efficient use.

A substantial modification of the national energy mix, which is highly dependent on the import of fossil fuels and hit by cyclical energy deficits, is a matter of national security

However, regulations with certain customs exemptions and other incentives to increase the production of solar, wind, biomass and hydroelectric energies in this Caribbean island nation still seem insufficient in view of the high prices of these technologies, the domestic economic crisis and the meager purchasing power of most Cuban families.

Clean sources account for only five percent of the island’s electricity generation, a scenario that the government wants to radically transform, with an ambitious goal of a 37 percent proportion by 2030, which is increasingly difficult to achieve.