Podcast Transcript

Epidemic: “Eradicating Smallpox”

Season 2, Episode 6: Bodies Remember What Was Done to Them

Air date: Oct. 10, 2023

Editor’s note: If you are able, we encourage you to listen to the audio of “Epidemic,” which includes emotion and emphasis not found in the transcript. This transcript, generated using transcription software, has been edited for style and clarity. Please use the transcript as a tool but check the corresponding audio before quoting the podcast.

Céline Gounder: In the early 1970s, all around the world, worries about overpopulation were mounting.

Politicians warned about the dangers.

Richard Nixon: Our cities are gonna be choked with people. They’re going to be choked with traffic. They’re gonna be choked with crime. … And they will be impossible places in which to live.

Céline Gounder: And news outlets repeated the claims. A 1970 news analysis from The New York Times described “two avenues” to deal with the problem of overpopulation.

Voice actor reading from NYT article: “… one is persuasion of people to limit family size voluntarily, by contraception, sterilization or abortion. The other is compulsory, through such means as large‐scale injection of at least temporary infertility drugs into food or water.”

Céline Gounder: Popular books like “The Population Bomb” suggested an impending, apocalyptic future. Pulpy paperbacks were passed around — capturing people’s imagination and stoking fears.

Two million copies of “The Population Bomb” were sold. And the author landed on late-night television, his dire predictions becoming entertainment for Americans sitting at home on their couches.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the globe, India — with its growing population — was in the crosshairs of the world’s anxieties.

[Solemn music plays.]

Céline Gounder: In the early ’50s, India had launched a family planning program.

Narrator of Indian Family Planning Film: There are 5 million more mouths to feed every year. … If our population continues to grow unchecked at the present alarming rate, we cannot solve our problems of food and shelter.

Céline Gounder: And that state-sponsored campaign got political and financial backing from international organizations like the World Bank and American foundations like Ford and Rockefeller.

Health workers were dispatched across India to get people to have fewer children.

Sometimes voluntarily.

Sometimes for a monetary reward.

Sometimes using force.

Violence and coercion created distrust.

In this episode, we’ll explore how that distrust affected the public health campaign to stop smallpox.

And ask: What is the path to restoring trust?

I’m Dr. Céline Gounder and this is “Epidemic.”

[“Epidemic” theme music plays.]

Chandrakant Pandav: Ready? Good afternoon. My name is Dr. Chandrakant Pandav. This is a recording in my office at New Delhi.

Céline Gounder: Chandrakant Pandav’s office is decorated with his academic degrees, lantern lights, and floral wallpaper. There are photos of Mahatma Gandhi, Mother Teresa, and various Hindu deities framed in gold.

And on his desk is a small saffron-white-and-green flag.

Chandrakant Pandav: Most important, I have India’s flag always in front of me.

Céline Gounder: And what’s the reason for that?

Chandrakant Pandav: Patriotism, mera desh mahaan.

Céline Gounder: Mera desh mahaan — “My great Nation”— he says in Hindi. Chandrakant was so eager to share his pride that at one point he picked up the flag and waved it around a bit.

He could barely contain his love for his country — and its culture.

He even got up out of his chair, turned on a song, and started dancing.

[Video of Chandrakant dancing to upbeat music playing.]

Céline Gounder: A twist of the hand here, a little shimmy there; he did a few hand mudras with a look of delight on his face.

I couldn’t help but smile along with him.

[Dance video continues playing, Céline and Chandrakant laugh.]

Céline Gounder: But even with all that joy, when the music stopped and he shuffled back to his chair, you’re reminded that Chandrakant is in his 70s, with more than 50 years of experience in public health.

[Video of Chandrakant dance video fades out.]

Céline Gounder: He was one of thousands of people asked to take part in the smallpox eradication program in the early and mid-’70s. He didn’t hesitate when he got the call.

Chandrakant Pandav: I said, this is the time to serve my India. Because India has spent so much of money on my education and making me a doctor, so I came from this culture strong, strong ethical background that your life is not for yourself. Money is … doesn’t matter. Serve the society.

Céline Gounder: Chandrakant led a team of smallpox eradication workers. He says nearly every person he talked to about taking the smallpox vaccine seemed to have the same worry, the same questions.

Chandrakant Pandav: “What is this vaccine? What is this you’re doing us? Maybe it’s a population control measure.” So the strongest question they had: “This is the government of India’s new policy for sterilization?”

Céline Gounder: Sterilization. The government’s decades-long family planning campaign was very much top of mind.

Decades later, when Chandrakant thinks about the program — and the unethical tactics India used — the pride melts off his face.

Chandrakant Pandav: It was a very aggressive strategy, unfortunately. I don’t want to go into that period. It was very aggressive.

Céline Gounder: Chandrakant didn’t want to talk about it. But you can’t tell the story of smallpox eradication success without talking about the family planning policies that came first.

Without talking about the state-sponsored coercive tactics that were commonplace and accepted by many.

Without acknowledging the violence of forced sterilizations.

Public health doesn’t happen in a vacuum.

And India’s approach to family planning eroded trust in public health workers for years.

So — in this season all about smallpox — we’re going to spend some time this episode diving into the details of the family planning program.

Gyan Prakash: My name is Gyan Prash and I’m professor of history at Princeton University.

Céline Gounder: Gyan has spent years studying India’s family planning campaign and the various tactics the government used to sterilize millions of people.

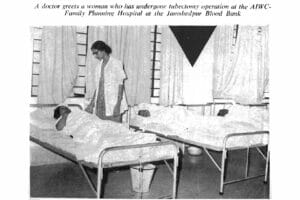

The government would pay people to get sterilized, and after natural disasters, like a drought, when many were desperate, any amount of money could be a powerful motivator. Patients might receive fewer than 100 rupees as compensation — which translates to only a few days’ wages, according to a 1986 article published in the journal “Studies in Family Planning.”

Gyan Prakash: It was a very small amount, but it mattered; it mattered to the poor. It was coercive, because it was between going hungry and, and not going hungry.

Céline Gounder: And if you chose not to get sterilized, Gyan says, the government found other ways to twist the screw. Families would receive food rations for up to only three children — any child beyond that would not be allotted food.

Gyan Prakash: Which punishes families which have more than three children.

Céline Gounder: At one point, the government began to prioritize men for sterilization.

Vasectomies were sometimes pushed on men, according to a 1972 report from The Associated Press.

Céline Gounder: Gyan says India’s family planning campaign created an atmosphere of intimidation and harassment that was nearly impossible to escape.

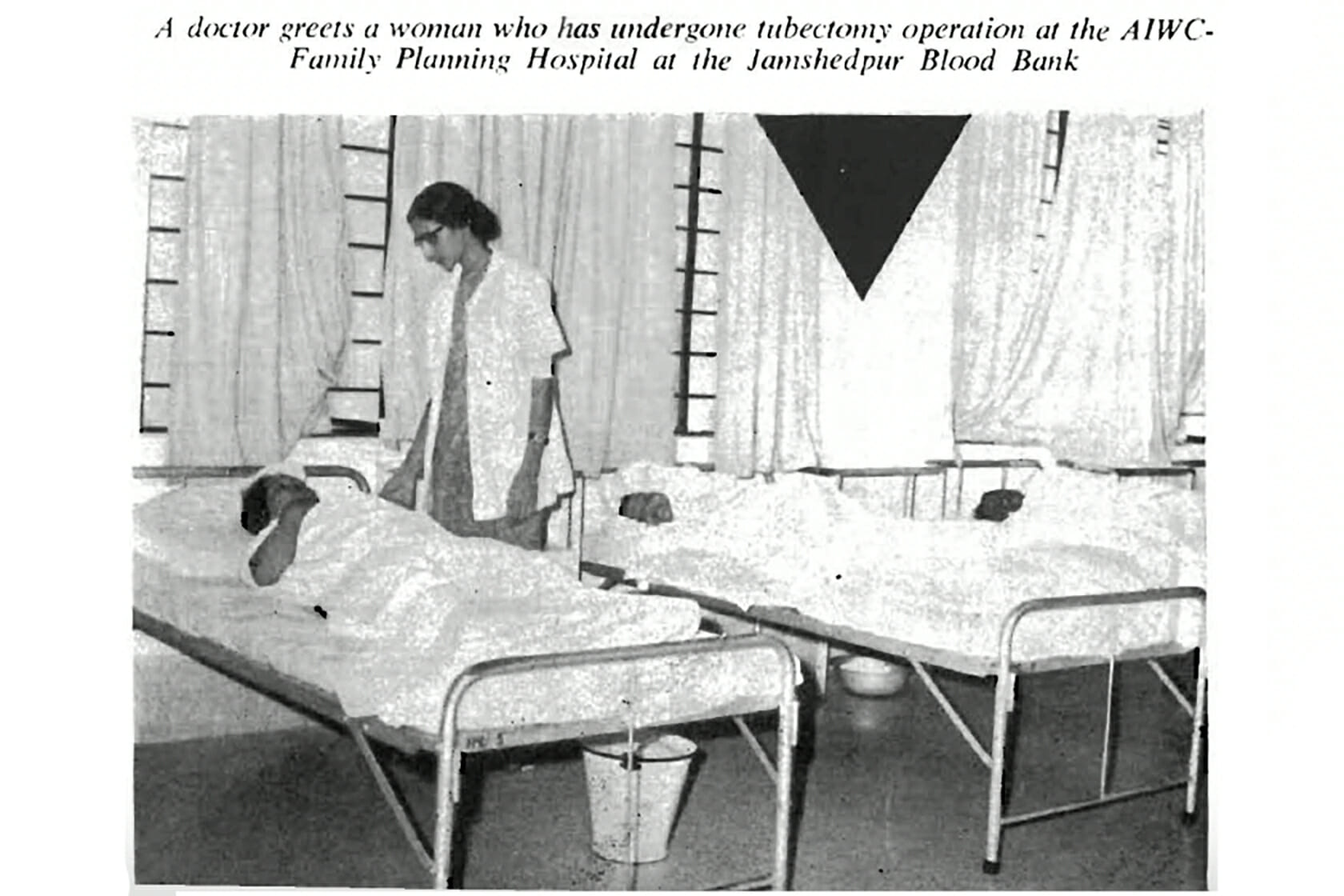

Gyan Prakash: You know, sending district authorities, backed by police, to the countryside and hold sterilization camps. So, I mean, the entire state machinery was mobilized to get people to the sterilization table.

Céline Gounder: Some of the harshest treatment during the sterilization campaign was aimed at Muslims and Indigenous populations like Adivasi tribes living in remote and rural parts of the country. I spoke to Sanjoy Bhattacharya about this.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya: I’m a historian of medicine with a deep interest in health policy, national, international, and global. And I’m the head of the School of History at the University of Leeds, United Kingdom.

Céline Gounder: Sanjoy says marginalized communities were often scapegoated.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya: That global narrative of overpopulation took the shape of, oh, Muslims have more children than Hindus, therefore Muslims are the problem behind Indian overpopulation. So we need to control the Muslim birthrate. What sterilization did was to violently sterilize men from a certain community who were blamed for a population problem that was a general population problem.

Céline Gounder: Sanjoy says many Adivasi and Muslim communities, in particular, lost trust in the government. This distrust lingered and simmered for years.

Imagine for a moment that for decades government trucks have descended on your village unannounced. Tents were set up. Equipment was unloaded. Workers fanned out to talk to village leaders.

This is what it looks like when Indian health workers showed up to sterilize you and your people.

And then, in the early 1970s, more government trucks arrived, maybe with familiar faces at the wheel. Maybe it’s some of the same public health workers.

They unload similar sharp-edged tools and set up their tents, but this time they promise it’s not for sterilization, it’s for a smallpox eradication program. You’d have a hard time trusting them.

Sanjoy Bhattacharya: And there are tales of how villages would empty when rumors would spread that these teams were coming ostensibly to vaccinate, but maybe really to sterilize. I mean, people’s bodies still remember what was done to them.

Chandrakant Pandav: They were treated like animals. Coercion, coercion, coercion.

Céline Gounder: That’s community medicine physician and longtime public health leader Chandrakant Pandav again. He says when he arrived in the northern region of the state of Bihar, he knew these communities had every reason to doubt his team.

So first he worked to earn people’s trust.

Chandrakant Pandav: So when you sit with the leader of the village, along with the batch of people there, you talk to them, you explain to them.

Céline Gounder: And Chandrakant says it’s helpful to think of yourself more as a guest than a guest of honor.

Chandrakant Pandav: You don’t sit on a chair. Céline, I didn’t sit on a chair. I sat next to them to make them feel that I’m part of that community.

Céline Gounder: It sounds like convincing the village leader was enough to convince the villagers.

Chandrakant Pandav: It is the first step.

Céline Gounder: Another important step, he says, was to learn the local traditions around smallpox. Locals in Bihar faced the disease for many years, and they’d developed their own ways of dealing with it.

They would tie the leaves of a neem tree outside the homes of infected people.

The neem tree is said to have medicinal properties. Displaying its leaves outside homes where an active infection was present alerted others to stay away — a strategy designed to slow disease spread.

It didn’t stop the virus — it wasn’t effective in the same way as vials of vaccine or the bifurcated needle — but the traditions needed to be honored.

So Chandrakant and the other public health workers adopted some of the local strategies.

Chandrakant Pandav: So it was a very good combination of ancient medicine, ancient practice, with modern approach. Very good combination.

Céline Gounder: Another tradition his team tapped into was folk songs. They frequently used drums, songs, and the public address systems to communicate with people about smallpox.

Music was an especially good match for Chandrakant’s lively personality.

Remember all that joy for India I witnessed in his office in New Delhi — the flag? The dancing? Imagine that harnessed on behalf of his mission to wipe out smallpox.

In fact, he still remembers some of those folk songs nearly half a century later.

Chandrakant Pandav: Because it’s part of me, every atom, every molecule residing [sings folk song in Hindi]. So, it became an important method of communication. I come back again and again, Céline, to the same point: Establish a rapport and instill a sense of faith, anything is possible.

Céline Gounder: Chandrakant was able to pave the way for acceptance of the smallpox vaccine and rebuild trust in public health. But he was one charismatic man. His approach, his compassion were admirable — and it worked, where he was, with the people in front of him.

But the Indian government broke trust with tens of millions of its citizens during the family planning campaign. It makes me wonder about what it might look like to repair trust at that level, across the public health system, across an entire country.

Maybe that would mean an apology. Maybe that would be some kind of reparation to victims for the damage done to their bodies.

My friend and colleague Tom Bollyky says there’s no single silver bullet for rebuilding trust.

Tom Bollyky: That is too big of a mission for public health. We have enough challenges as it is. Instead of planning for how do we rebuild trust, we should be planning for dysfunction.

Céline Gounder: That’s after the break.

[Music fades out.]

Céline Gounder: Distrust and mistrust in the government became something of a defining feature of the response to the covid pandemic here in the United States. And while that might have taken many Americans by surprise, it was totally predictable to Tom Bollyky. He’s the director of the global health program at the Council on Foreign Relations. Bollyky says trust in the U.S. has been deteriorating since Watergate, and that decline accelerated around the 2008 financial crisis. Mistrust here divides along racial lines. It’s lower among African Americans, for example. And most notably, mistrust tends to be partisan. But it didn’t start that way during the covid pandemic.

Tom Bollyky: I think we all forget that there was, for a period of time, a surprising level of political consensus. Almost all states imposed protective policy mandates and most states imposed them at the same time. But as the fall stretched out, you saw some of those mandates and responses become more politicized.

And the moment I regret is, I think there was a moment, when the Biden administration came in and there was an attempt to reset and I … myself and many others really again focused on this message of following the science. But I do feel like perhaps we missed a opportunity to try to pull in some people across partisan lines at that moment.

Céline Gounder: So, as I’m hearing you describe this, restoring trust seems like a really massive undertaking.

I wonder whether you think that’s even the right framework that we should be using to think about this challenge.

Tom Bollyky: Such a great question. No, I think it isn’t. I think if we set an agenda for public health to rebuild the cohesiveness of our societies, to make us have a better relationship with our government, with each other, we will fail.

That is too big of a mission for public health. We have enough challenges as it is. Instead of planning for how do we rebuild trust, we should be planning for dysfunction. That’s really what preparedness is about.

Céline Gounder: So what are some of the ways that public health officials can reach skeptical communities?

Tom Bollyky: Through kinship networks and, uh, local leaders has been important. In some other public health crises, like HIV, people have used soap operas.

Céline Gounder: I remember being in South Africa in the early 2000s. There was a soap opera called “Soul City.” We pulled a clip of it, and there’s this one scene where a husband comes home to find his wife has placed a romantic gift by their bedside. He opens it up and sees condoms.

[Music]

“Soul City” clip: Woman: So that we can have safe sex. Man: Safe sex. Woman: I can’t have sex with you while I’m anxious about getting sick. Or, would you prefer I use condoms maybe? Man: We don’t need condoms. Woman: I do.

Tom Bollyky: I was in South Africa and the country was riveted. People really talked about it. It took, it took hold. Uh, they did a nice job of making it interesting, like weaving in the themes you wanted to weave in about people getting tested and talking to their partners and loved ones about their circumstances.

I know, Céline, you were very involved in the Ebola response, in 2013 through 2016. You know, there is high levels of mistrust in government in those post-conflict settings that were most affected in that epidemic.

Céline Gounder: People there don’t trust government, they think that people who serve in government do so to enrich themselves and their family and friends.

When I was in Guinea during the Ebola epidemic, they said Ebola was a hoax, that it was just a way for government officials and international organizations to enrich themselves. And yet, we were able to make some inroads convincing people to comply with Ebola control measures, so hand-washing, testing, safe burials.

Much of that was done through imams and other religious and community leaders.

Tom Bollyky: Those are the types of strategies we should be deploying when the next health crisis emerges, but not simply waiting until that happens. We need to start to build the infrastructure, the relationships. Again, even if it isn’t around fundamentally transforming, you know, communities, relationships with the government, or even how community members feel about, uh, one another, because interpersonal trust, social trust is a big part of this, too.

It’s about building the connections, the networks, about starting to engage individuals in these programs or through those institutions so that when the crisis emerges, you’re not building that from scratch.

Céline Gounder: Well, and to your point, as we prepare for the next pandemic, do you think we’ve learned those lessons about trust or are there things we’re still getting wrong?

Tom Bollyky: I think there is a greater appreciation for trust as an important issue. You hear that messaging. What I worry about is we’re not seeing it reflected yet in where the money is going. Where the money is going by and large is to developing vaccines faster, better vaccines in the future. But if really the lessons we’re drawing from this crisis are that developing a vaccine instead of in 326 days in 250 days … if we really think that would have made a difference in this pandemic, we haven’t been paying attention.

Céline Gounder: Next time on “Epidemic” …

Daniel Tarantola: They did not consider smallpox as the major issues among the many issues they were confronting. … No. 1 priority is food and food and food. And the second priority is food and food and food.

CREDITS

Céline Gounder: “Eradicating Smallpox,” our latest season of “Epidemic,” is a co-production of KFF Health News and Just Human Productions.

Additional support provided by the Sloan Foundation.

This episode was produced by Taylor Cook, Zach Dyer, Bram Sable-Smith, and me.

Saidu Tejan-Thomas Jr. was scriptwriter for the episode.

Swagata Yadavar was our translator and local reporting partner in India.

Our managing editor is Taunya English.

Oona Tempest is our graphics and photo editor.

The show was engineered by Justin Gerrish.

We had extra editing help from Simone Popperl.

Music in this episode is from the Blue Dot Sessions and Soundstripe.

This episode featured clips from National Education & Information Films Limited

We’re powered and distributed by Simplecast.

If you enjoyed the show, please tell a friend. And leave us a review on Apple Podcasts. It helps more people find the show.

Follow KFF Health News on X (formerly known as Twitter), Instagram, and TikTok.

And find me on X @celinegounder. On our socials, there’s more about the ideas we’re exploring on our podcasts.

And subscribe to our newsletters at kffhealthnews.org so you’ll never miss what’s new and important in American health care, health policy, and public health news.

I’m Dr. Céline Gounder. Thanks for listening to “Epidemic.”

[“Epidemic” theme fades out.]