CopyRight @2009 The Maravi Post , An Eltas EnterPrises INC Company Since @2005. Publishing and Software Consulting company

Contact us: contact@maravipost.com

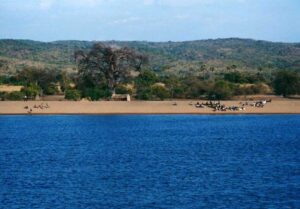

Malawi (/məˈlɔːwi, məˈlɑːwi/; Chichewa pronunciation: [maláβi]; Tumbuka: Malaŵi), officially the Republic of Malawi and formerly known as Nyasaland, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south and southwest. Malawi spans over 118,484 km2 (45,747 sq mi) and has an estimated population of 19,431,566 (as of January 2021). Malawi’s capital and largest city is Lilongwe. Its second-largest is Blantyre, its third-largest is Mzuzu and its fourth-largest is its former capital, Zomba.

CopyRight @2009 The Maravi Post , An Eltas EnterPrises INC Company Since @2005. Publishing and Software Consulting company

Contact us: contact@maravipost.com

Dressing for winter doesn’t have to mean hiding behind oversized layers or settling for shapeless silhouettes. With the right design details, a dress can instantly create a sleeker, more balanced look while still feeling cozy and wearable. These winter styles are proof that built-in flattery makes all the difference.

Each option below features thoughtful elements that help smooth the belly and define your shape naturally. Think effortless wrap dresses you can reach for on busy mornings and still feel confident walking out the door. Best of all, these flattering finds start at just $24, making them easy to add to your winter rotation.

1. Our Favorite: Not only does this belted knit maxi slim the waist, its vertical stripe details visually slim as well.

2. Curve-Accentuating: A belted wrap dress like this one highlights the waist while softly skimming the midsection.

3. Waist-Slimming: Thanks to its cinched waist, this flowy maxi dress offers shape without clinging.

4. Mocha Moment: Not only does this stunning eyelet dress have a pretty design, but it also has built-in pockets.

5. Belted Beauty: With smartly placed pleats, this belted knit midi avoids clinging and stays flattering.

I’d Easily Mistake These 17 Zara-Style Sets for Celeb Airport Looks

6. Our Favorite: Office-ready and refined, this pleated knit dress falls smoothly through the midsection.

7. Two-in-One: For more casual days, you’ll want to reach for this Dressing for winter that’s a skirt and long-sleeve all in one.

8. Pleated Perfection: This pleated wrap dress delivers a smooth, polished silhouette that looks good from every angle.

9. Fabulous Flowy: From meetings to dinner plans, this elegant knit maxi offers a sleek, belly-skimming fit.

10. Our Favorite: This fit-and-flare midi proves comfort doesn’t have to come at the expense of a flattering fit.

11. Has Pockets: For days when function comes first, this built-in flattery comes equipped with handy pockets.

12. Must-Have Maxi: This short-sleeve maxi earns its keep, layering beautifully now and wearing effortlessly into spring.

13. Plaid Perfection: Soft and wearable, this plaid mini dress offers comfort with a flattering, easy drape.

14. Our Favorite: This wrap maxi dress creates an elegant silhouette that smooths through the torso.

15. Floral Favorite: With its smocked waist, this floral midi dress offers subtle shaping for winter formal looks.

16. Swiss Dot Stunner: This Swiss dot maxi feels made for elevated occasions, with a defined waist and a graceful pleated skirt.

17. Try it Tiered: With its tiered design, this chiffon midi dress cleverly conceals the midsection.

If You Love Barrel Jeans, You’ll Swoon Over These 17 Barrel-Leg Sweatpants

Us Weekly has affiliate partnerships. We receive compensation when you click on a link and make a purchase. Learn more!

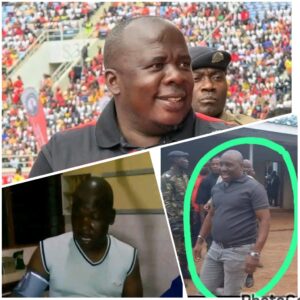

LILONGWE-(MaraviPost)-Human rights activist Chimwemwe Mbeya Mhango Ntchindi has slammed Malawi Congress Party (MCP) zealot Dala Kadula for threatening to deal with Frank Chiwanda over MCP Secretary General Richard Chimwendo Banda detention.

Mhango, the former Malawi Defence Force (MDF) officer is reacting to social media audio circulation which Kadula is heard threatening Chiwanda for initiating Chimwendo’s arrest in attempted murder case.

In an audio which The Maravi Post Post posted a day ago, Kadula who is also answering assault charges in court questioned Chiwanda as to why he initiated Chimwendo’s arrest.

Kadula further threatened to deal with Chiwanda if Chimwendo remains in cell.

But reacting to the audio, Mhango expressed worrisome over Kadula’s unpalatable behaviour of threatening others despite being in court on similar charges.

“Is Kadula really normal? Why he continues to pose threats to others despite being dragged to court on similar charges?

“What if MCP was still in power, what could be the fate of us whom he also threatened to kill?”, he queries.

The activist adds, “This behaviour is a threat to our society that is aimed at violating people’s rights.

“It’s my appeal to authorities to put this to stop. Let the law take its course on this uncalled for inhumane characters.

According to court documents, Kadula is Chimwendo Banda’s accomplices in attempted to Frank Chiwanda in 2022 in Dowa.

However, the court stopped Kadula’s arrest as he is also answering others assault charges.

But with this behaviour, the court might revoke the bail as he posses threat to society.

MCP Secretary General Chimwendo has been on detention for a month now as the court is yet to grant him bail.

But Chimwendo has not been fully charged in the court.

Kylie Jenner’s full-bodied new fragrance is out … and, she’s using her bust to promote it — pushing up her cleavage for the ad. The model posed in the sleeveless red leather top which perfectly matched the fragrance bottle she held against her…

Madison Chock and Evan Bates both remember the moment everything changed.

The Team USA ice dancers — widely regarded as the best duo in the world and the favorites to win gold at the 2026 Winter Olympics in Italy — were originally paired together in 2011.

Over time, however, their professional partnership blossomed into something more.

“There’s definitely a moment that I recall,” Bates, 36, exclusively told Us Weekly alongside Chock, 33, via their partnership with Nulo. “We skated together for five years and it was just a friendship, but the friendship was good. From day one we always had a connection. We were laughing, we enjoyed our time together. It made skating so fun. Over the five years, we had success, but also didn’t have success. We had a lot of trying times. In those trying times, I really realized how much I relied on Maddie and really felt connected to her in a way that went beyond just as a skating partner.”

Olympic Ice Dancers Evan Bates and Madison Chock’s Relationship Timeline

As the pair prepared to compete at the 2018 Winter Olympics in PyeongChang, Bates had the impression “it was going to be the end of the road for us as a career.”

“I remember thinking, ‘I can’t really imagine one day walking out of the rink and going our separate ways, being friends and just not seeing each other anymore,’’’ Bates said. “I made the realization, I shared the realization and, luckily, the realization was reciprocated. That changed everything in our relationship and our partnership.”

Bates added, “Since that moment, we’ve been pretty much inseparable.”

Chock remembers the moment, too, admitting she was “so surprised” by Bates’ admission.

“It really just came out of the blue for me,” she told Us. “I knew we always had an incredible chemistry. We had so much fun together. We were great friends. Training was always fun because we always just got along. We had the same work ethic. But when he told me how he felt, I was so surprised because I didn’t see it coming at all.”

Chock continued, “When I really sat with it and thought about it, I was like, ‘Wait a minute. I feel the same things about you. This is incredible.’”

The couple got married in Hawaii in June 2024.

“Our day-to-day life is certainly very similar, if not completely unchanged with training and our typical routine that we have gotten used to over the years,” Chock said of life as husband and wife. “But I would say after we got married there was definitely a shift in the emotional connection and pull towards each other. It’s definitely much stronger.”

Chock added, “It’s very rooted in love and our commitment to each other, and our commitment in wanting to continue to improve as people moving forward and be the best partners we can be to each other.”

With the 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan and Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy, on the horizon, Chock and Bates have partnered with Nulo’s “Fuel Incredible” campaign, designed to highlight the unique bond between athletes and their pets.

Team USA’s Dating Histories: Inside the Winter Olympians’ Love Lives

Chock and Bates are parents to toy poodles Stella, 13, and Henry, 9.

“Henry and Stella are a huge part of our lives,” Chock said. “Skating is a huge part, but Henry and Stella are right there along with us. They’re really an active part of our entire day.”

During training, Chock said both dogs “come with us to the rink on a daily basis.”

‘When we have a break, they run around and they greet everybody in the locker room,” Chock explained. “They just brighten spirits at the rink when everyone’s going through the ringer. Doing their run-throughs, having some grueling training sessions. Henry and Stella bring everybody so much joy.”

Zara Larsson’s drawing a line in the sand … telling fans she loves a lot of controversial people and activities — but definitely not ICE. The “Lush Life” hitmaker shared a list of her likes and dislikes on Instagram Saturday morning … telling…