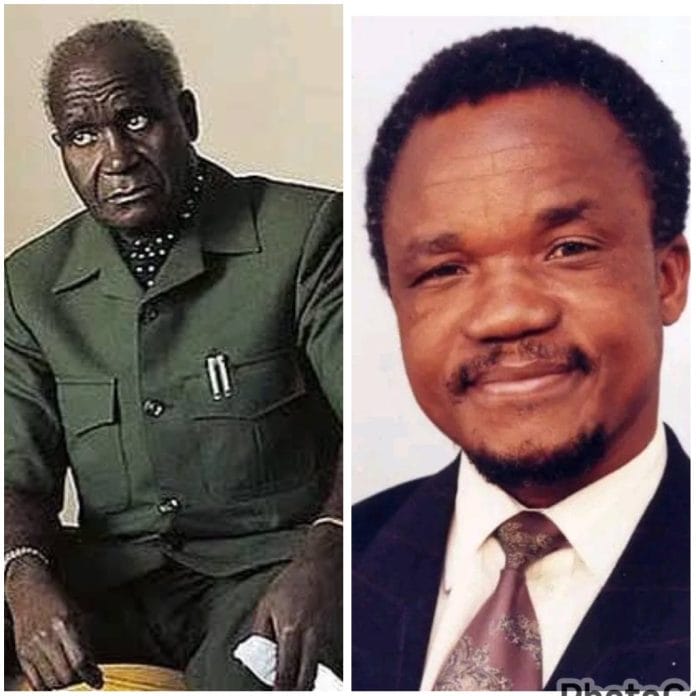

LUSAKA-(MaraviPost)-When Zambia transitioned from Kenneth Kaunda’s 27-year rule to Frederick Chiluba’s new multiparty era, the change appeared peaceful on the surface.

However, beneath the handshake diplomacy, one of Southern Africa’s most psychologically brutal political confrontations was unfolding.

On Christmas Day, 1997, Kaunda was arrested, a moment chosen for maximum symbolic impact.

Christmas, traditionally a day of presidential addresses and national unity, became the backdrop for Kaunda being bundled into a vehicle by armed officers.

The timing led many senior diplomats to conclude that the arrest was meant to break Kaunda psychologically, rather than simply pursue legal action.

The government accused Kaunda of involvement in a failed coup in October 1997, led by junior soldiers.

Yet Zambian intelligence insiders later admitted that there was no concrete evidence linking Kaunda to the mutiny.

Kaunda had been out of power for six years, had no military command, and was leading a peaceful political movement under UNIP.

Despite this, he became the central figure blamed for a coup he did not participate in.

At the time, Kaunda was experiencing an unexpected political resurgence, drawing large crowds to his rallies and maintaining widespread respect across rural districts.

Inside State House, Chiluba’s camp feared that Kaunda could potentially win the 1998 elections if allowed to run.

Kaunda’s moral authority still overshadowed other political figures and remained a unifying force across tribal lines, unlike the fragmented new elite.

For many observers, his arrest was interpreted as a pre-emptive political strike rather than a measure of national security.

During the same period, Kaunda was shot in the neck by government forces while leading a peaceful protest.

This injury left him physically vulnerable at the time of his detention.

For many Zambians, this act reinforced the perception that the state was willing to use lethal force against a national symbol.

Kaunda was subsequently held in Mukobeko Maximum Security Prison, a facility typically reserved for murderers, armed robbers, and political radicals.

This was not merely imprisonment but an attempt to erode his legacy by equating him with dangerous criminals.

Some prison officials later revealed they were instructed to treat Kaunda “as an ordinary dangerous suspect,” delivering a psychological blow aimed at undermining his stature.

The international community, including the Commonwealth, the United Nations, and African heads of state, intervened behind the scenes to pressure Chiluba to release Kaunda.

Even Nelson Mandela reportedly sent private messages condemning the treatment of the former president.

Diplomats feared that Zambia was descending into personal vendetta politics, with the potential to trigger ethnic tensions or civil unrest.

Chiluba’s own cabinet was divided on the matter, with some ministers warning that humiliating Kaunda could backfire politically.

Nevertheless, hardline security advisors convinced Chiluba that neutralising Kaunda was essential to consolidating power.

Ironically, the detention had the opposite effect of what Chiluba intended.

Kaunda emerged from prison more respected, seen as a statesman, and admired internationally as a martyr of democratic abuse.

The attempted political witch hunt, while meant to cripple Kaunda’s comeback, ultimately strengthened his legacy.

Historians agree that there was no direct evidence linking Kaunda to the coup, the arrest’s timing and style were deeply political, and Chiluba had strong incentives to remove a key rival.

Official statements cited national security, but the methods, symbolism, and sequence of events pointed clearly to a targeted political campaign.

The detention of Kaunda remains a powerful reminder of how political power struggles can shape the destiny of nations and the enduring respect commanded by principled leadership.

Discover more from The Maravi Post

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.