Asia-Pacific, Conferences, Development & Aid, Featured, Headlines, Health, Human Rights, Poverty & SDGs, TerraViva United Nations, Women’s Health

Mr Yohei Sasakawa, chairman of the Nippon Foundation and Sasakawa Health Foundation and WHO Goodwill ambassador. Credit : Crystal Orderson / IPS

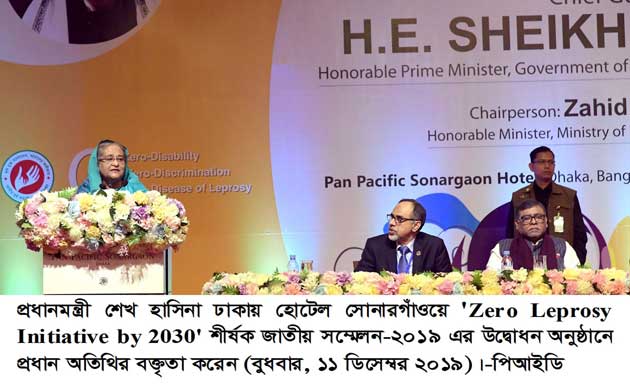

– Leprosy is not a curse but should be detected and treated early, Bangladeshi Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina, has told delegates at a gathering in her country’s capital to discuss the elimination of the disease.

“In the past, it was thought that leprosy was a curse. But it was not a curse at all. The disease is caused by bacteria (Mycobacterium Leprae). We should fight it through research,” Hasina said, adding that the discrimination against leprosy sufferers should end. She called upon all concerned to work together so that Bangladesh could be leprosy-free before 2030.

Prime Minister Hasina, who spoke in Bengali at the National Conference 2019 on Zero Leprosy Initiatives by 2030, also committed her government to proper treatment for leprosy sufferers.

To achieve these targets, the country’s National Leprosy Programme, in collaboration with the Nippon Foundation and Sasakawa Health Foundation in Japan, has worked tirelessly to convene the conference, bringing together hundreds of health workers, medical professionals and district officers to discuss the issue under the theme “Zero Leprosy Initiatives”.

Certain areas in Bangladesh are particularly leprosy-prone, including its northern region and the Chittagong Hill Tracts, Prime Minister Hasina said.

Sheikh Hasina, Prime Minister of Bangladesh.

“If we can give special focus to these areas, I do believe it would be quite possible to declare Bangladesh a leprosy-free country before 2030,” she added.

“Leprosy patients must be considered on humanitarian grounds. If we all take a little responsibility in this regard, they will get recovery from this disease … I think we can do so,” Prime Minister Hasina said.

Distribute drugs free of cost

The prime minister said many Bangladeshi pharmaceutical companies export medicines, and she called upon these companies to produce drugs for leprosy locally and distribute those among leprosy patients free of charge.

The prime minister also warned that no-one could fire leprosy patients from their jobs but rather should arrange treatment for them.

End stigma and discrimination

The Chairman of the Nippon Foundation and World Health Organization (WHO) Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination, Yohei Sasakawa, says leprosy is not only a medical issue but also a social issue “because of the stigma and discrimination that the disease attracts”.

He said: “We have an effective cure for leprosy, and it is essential that every person with the disease has access to the cure and is diagnosed and treated in a timely fashion. With timely diagnosis and treatment, a patient can be cured without disability.

“This conference presents us with an opportunity to re-focus efforts on leprosy and aim at an ambitious target: zero leprosy by 2030,” Mr Sasakawa added.

The WHO Representative to Bangladesh, Dr Bardan Jung Rana, told delegates that leprosy has caused immense human suffering when those affected remained untreated.

“With the aim of a leprosy-free world, WHO is committed to providing technical and strategic guidance, strengthening country-level capacity and delivering interventions through appropriate technology at affordable costs,” said Dr Jung Rana.

Leprosy a treatable disease

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease affecting mainly the skin, the peripheral nerves, the mucosa of the upper respiratory tract, and the eyes. Leprosy is curable and treatment has been available through the WHO free of charge to all patients worldwide since 1995.

The history of leprosy dates back centuries in Bangladesh. Different Christian missionary organizations used to provide leprosy services in various high endemic areas in the country. In 1965 the government sector implemented leprosy services through three public hospitals.

Eliminating leprosy in Bangladesh

Despite its efforts to eliminate leprosy as a public health threat, Bangladesh’s leprosy burden ranks fourth-highest in the world. Four thousand new cases are detected annually – an average of 11 to 12 cases per day over the last 10 years. Every year an estimated 3000 leprosy sufferers are affected by complications that require specialized treatment in hospital.

Although the the number of leprosy cases are declining, more than one-third of leprosy patients are facing the threat of permanent and progressive physical and social disability. The human suffering resulting from the physical deformities and related social problems are immense.

Activists and community workers in Bangladesh welcomed the government’s commitment to ensure proper treatment for leprosy sufferers.

Delegates at National Conference 2019 Zero Leprosy Initiative by 2030, Dr Sr Roberta Pignone, PIME sisters (middle). Credit : Crystal Orderson / IPS

Stop pushing Leprosy in a corner

Dr Sr Roberta Pignone, Project Director of the Missionary Sisters of Mary Immaculate (with the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions (PIME) Sisters) in Khulna in the south of Bangladesh, told IPS: “It is good to listen to the prime minister and health officials and hear what they say they will do in the future to eliminate leprosy.” She added: “Leprosy is always pushed in a corner. It is good to hear that the government is aware of the disease. If the prime minister speaks to the nation, they will listen.”

The PIME Sisters have been working with leprosy since the mission opened its doors in 1986. “Sometimes leprosy is neglected and this conference shows that the government is committed to deal with leprosy,” says Dr Sr Pignone. “It is time to accept that leprosy is in the country and to deal with the situation.”

The Nippon Foundation and the Sasakawa Health Foundation of Japan organized a national conference on leprosy in Dhaka on December 11 under the theme “ZeRo leprosy initiative”.