Civil Society, Crime & Justice, Democracy, Featured, Headlines, Human Rights, Middle East & North Africa, TerraViva United Nations

Credit: Mohammed al-Shaikh/AFP via Getty Images

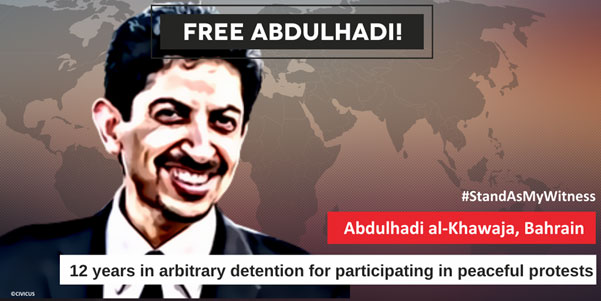

– Maryam al-Khawaja’s journey home ended before it had begun: British Airways staff stopped her boarding her flight at the request of Bahraini immigration authorities. Maryam was no regular passenger: her father is veteran human rights activist Abdulhadi al-Khawaja, in jail in Bahrain for 12 years and counting.

Abdulhadi was sentenced to life in prison on bogus terrorism charges for his role in 2011 democracy protests, part of the ‘Arab Spring’ regional wave of mobilisations. His health, weakened due to denial of medical care, has further declined as he joined other political prisoners in a hunger strike demanding improvements in prison conditions.

Emerging from the unlikeliest place – a prison designed to break wills and destroy the desire for freedom – this hunger strike has become the biggest organised protest Bahrain has seen in years.

Maryam has four judicial cases pending in Bahrain but was ready to spend years in prison if this was what it took to save her father’s life. This is far from Abdulhadi’s first hunger strike, but his family warns that his fragile health means it could be his last. In denying Maryam the chance to see her father, the Bahraini regime has reacted as those who rule by fear often do: in fear of those who aren’t afraid of them.

A prison state

The Bahraini cracked down severely on the 2011 protests, unleashing murderous security force violence to clear protest sites, arresting scores of protesters, activists and opposition leaders, subjecting them to mass trials and stripping hundreds of citizenship. It sentenced 51 people to death and has executed six, while 26 wait on death row having exhausted their appeals. Most were convicted on the basis of confessions obtained through torture.

Many of those arrested in the 2011 protests and subsequent crackdown remain behind bars. According to estimates from the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, over the past decade the government has arrested almost 15,000 people for their political views, and between 1,200 and 1,400 are still jailed, mostly in Jau prison in Manama, the capital. Abdulhadi is one of many.

On 7 August, Jau’s political prisoners went on hunger strike. Their demands include an end to solitary confinement, more time outside cells – currently they’re only allowed out for an hour a day, permission to hold prayers in congregation, amended visitation rules and access to adequate medical care and education. Over the following weeks the numbers taking part grew to more than 800. Their families took to the streets to demand their release.

On 31 August, the political prisoners extended their protest after rejecting the government’s offer of only minor improvements.

On 11 September, a two-week suspension of the strike was announced to allow the government to fulfil promises to improve conditions, including ending isolation for some prisoners. It seemed clear the government had shifted position to avoid embarrassment as Bahrain’s Crown Prince and Prime Minister Salman bin Hamad Al-Khalifa prepared to meet US President Joe Biden.

Abdulhadi, however, soon resumed his hunger strike after being denied access to a scheduled medical appointment, only to suspend it a few days later when he was promised improvements in conditions, including a cardiologist appointment. But the next day it became apparent that these were all lies, and he resumed his hunger strike. It felt, as Maryam put it, ‘like psychological warfare and an attempt to kill solidarity’.

International solidarity urgently needed

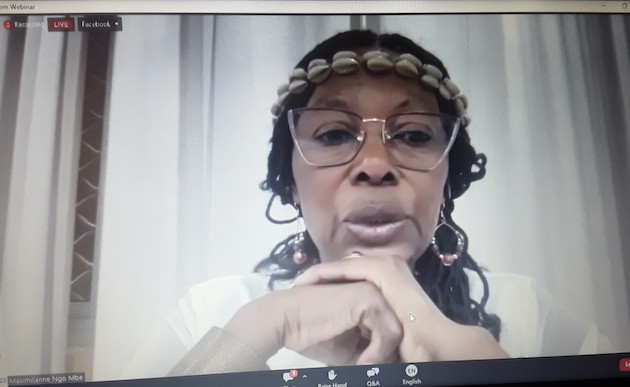

In her attempt to return to Bahrain, Maryam received strong international support. Several Bahraini, regional and international civil society groups backed a joint letter urging European Union authorities to call for the immediate and unconditional release of all Bahrain’s political prisoners. A similar letter was sent to the UK government.

In late 2022, backlash from human rights organisations forced Bahrain to withdraw its candidacy for a UN Human Rights Council seat. And earlier this year, during the Inter-Parliamentary Union’s global assembly in Bahrain, which the regime sought to use for whitewashing purposes, parliamentarians called on Bahrain to release Abdulhadi and send him to Denmark for medical treatment.

But while Bahrain’s political prisoners have many allies, some powerful voices aren’t among them.

Bahrain’s foreign allies include not only repressive autocracies such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates but also democratic states, notably the UK and the USA, which clearly value stability and security far more highly than democracy and human rights.

Following Bahrain’s independence in 1971, the UK has continued to back the institutions it established – and has pretended to see progress towards democratic reform. In July, Bahrain’s Crown Prince made an official visit to the UK, where he met Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and signed a ‘Strategic Investment and Collaboration Partnership’ between the two countries. This included a US$1 billion investment deal in the UK. Barely a month before the start of the hunger strike, Sunak welcomed ‘progress on domestic reforms in Bahrain, particularly in relation to the judiciary and legal process’.

For the USA, Bahrain has been a ‘major non-NATO ally‘ since 2002 and a ‘major security partner’ since 2021. Bahrain was the first state in the region to be accorded major non-NATO ally status, the first to host a major US military base and the first, in 2006, to sign a free trade agreement with the USA. The US Navy’s Fifth Fleet, one of seven around the world, is stationed there, and the country hosts the headquarters of the US Naval Forces Central Command.

On 13 September, the Crown Prince visited Washington DC and signed a ‘Comprehensive Security Integration and Prosperity Agreement’ meant to scale up military and economic cooperation with the USA.

Only in the last paragraph of its pages-long announcement, meticulously detailed in every other respect, did the White House briefly acknowledge that human rights were an item of discussion. Nothing was said about the content or outcome of those alleged conversations.

The USA has been repeatedly chastised for a ‘selective defence of democracy‘. President Biden promised a foreign policy centred around human rights, but that rings hollow in Bahrain. It’s high time the USA, the UK and other democratic states use the many levers at their disposal to urge the Bahraini government to free its thousands of political prisoners and move towards real democratic reform.

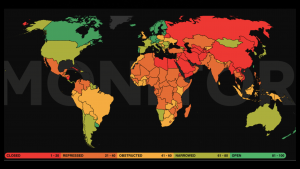

Inés M. Pousadela is CIVICUS Senior Research Specialist, co-director and writer for CIVICUS Lens and co-author of the State of Civil Society Report.