Civil Society, Democracy, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Headlines, Health, Human Rights, Latin America & the Caribbean, Population, Regional Categories

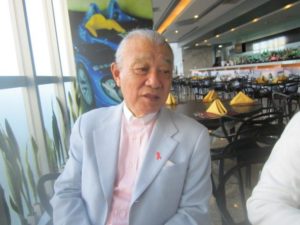

Nippon Foundation President Yohei Sasakawa and Socorro Gross, Pan American Health Organisation representative in Brazil, hold a press conference in Brasilia at the end of a 10-day visit to this country by the Japanese activist who is also World Health Organisation Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination. Credit: Mario Osava/IPS

– “The ambulance team refused to take my sick friend to the hospital because he had had Hanseniasis years before,” said Yohei Sasakawa, president of the Nippon Foundation, at one of the meetings held during his Jul. 1-10 visit to Brazil.

His friend was completely cured and had no visible effects of the disease, but in a small town everyone knows everything about their neighbours, he said.

This didn’t happen in a poor country, but in the U.S. state of Texas, only about 20 years ago, Sasakawa pointed out to underline the damage caused by the discrimination suffered by people affected by Hansen’s Disease, better known as leprosy, as well as those who have already been cured, and their families.

“The disease is curable, its social damage is not,” he said during a meeting with lawmaker Helder Salomão, chair of the Human Rights Commission in Brazil’s lower house of Congress, to ask for support in the fight against Hanseniasis, the official medical name for the disease in Brazil, where the use of the term leprosy has been banned because of the stereotypes and stigma surrounding it.

The highlight of the mission of Sasakawa, who is also a World Health Organisation (WHO) Goodwill Ambassador for Leprosy Elimination, was a meeting on Monday Jul. 8 with President Jair Bolsonaro, who posted a message on Facebook during the meeting, which had nearly 700,000 hits as of Thursday Jul. 11.

In the 13-and-a-half minute video, Bolsonaro, Sasakawa, Health Minister Luiz Mandetta and Women, Family and Human Rights Minister Damares Alves issued a call to the authorities, organisations and society as a whole to work together to eradicate the disease caused by the Mycobacterium Leprae bacillus.

A preliminary agreement emerged from the dialogues held by the Japanese activist with members of the different branches of power in Brasilia, to hold a national meeting in 2020 to step up the fight against Hanseniasis and the discrimination and stigma faced by those affected by it and their families.

The idea is a conference with a political dimension, with the participation of national authorities, state governors and mayors, as well as a technical dimension, said Carmelita Ribeiro Coriolano, coordinator of the Health Ministry’s Hanseniasis Programme. The Tokyo-based Nippon Foundation will sponsor the event.

Brazil has the second highest incidence of Hansen’s Disease in the world, with 27,875 new cases in 2017, accounting for 12.75 percent of the world total, according to WHO. Only India has more new cases.

The government established a National Strategy to Combat Hanseniasis, for the period 2019-2022, in line with the global strategy outlined by the WHO in 2016.

Brazilian Minister of Women, Family and Human Rights Damares Alves (L) receives a gift from Yohei Sasakawa, president of the Nippon Foundation, at the beginning of a meeting in Brasilia, in which the minister promised to strengthen assistance to those affected by Hansen’s Disease, including the payment of compensation to patients who were isolated in leprosariums or leper colonies in the past. Credit: Mario Osava/IPS

Extensive training of the different actors involved in the treatment of the disease and plans at the state and municipal levels, tailored to local conditions, guide the efforts against Hansen’s Disease, focusing particularly on reducing cases that cause serious physical damage to children and on eliminating stigma and discrimination.

Before his visit to Brasilia, Sasakawa, who has already come to Brazil more than 10 times as part of his mission against Hansen’s Disease, toured the states of Pará and Maranhão to discuss with regional and municipal authorities the obstacles and the advances made, in two of the regions with the highest prevalence rate.

“In Brazil there is no lack of courses and training; the health professionals are sensitive and give special attention to Hanseniasis,” said Faustino Pinto, national coordinator of the Movement for the Reintegration of People Affected by Hanseniasis (MORHAN), who accompanied the Nippon Foundation delegation in Brasilia.

“Promoting early diagnosis, to avoid serious physical damage, and providing better information to the public and physical rehabilitation to ensure a better working life for patients” are the most necessary measures, he told IPS.

Pinto’s case illustrates the shortcomings in the health services. He was not diagnosed as being affected with Hansen’s Disease until the age of 18, nine years after he felt the first symptoms. It took five years of treatment to cure him, and he has serious damage to his hands and joints.

His personal plight and the defence of the rights of the ill, former patients and their families were outlined in his Jun. 27 presentation in Geneva, during a special meeting on the disease, parallel to the 41st session of the Human Rights Council, the highest organ of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

Pinto is an eloquent advocate of the use of Hanseniasis or Hansen’s Disease, rather than leprosy, a term historically burdened with religious prejudice and stigma, which aggravates the suffering of patients and their families, but continues to be used by WHO, for example.

Yohei Sasakawa (2nd-L), president of the Nippon Foundation, accompanied by two members of his delegation, took part in a meeting with Congressman Helder Salomão (C), chair of the Human Rights Commission of the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies, who pledged to support initiatives to eliminate leprosy in his country. Faustino Pinto (2nd-R), national coordinator of the Movement for the Reintegration of Persons Affected by Hanseniasis (MORHAN), also participated. Credit: Mario Osava/IPS

Discrimination against people with the disease dates back to biblical times, when it was seen as a punishment from God, said Sasakawa during his meeting with Minister Damares Alves, a Baptist preacher who describes herself as “extremely Christian”.

In India there are 114 laws that discriminate against current or former Hansen’s Disease patients, banning them from public transport or public places, among other “absurdities”, he said.

In India, they argue that these are laws that are no longer applied, which justifies even less that they remain formally in force, he maintained during his meetings in Brasilia to which IPS had access.

Prejudice and misinformation not only subject those affected by the disease to exclusion and unnecessary suffering, but also make it difficult to eradicate the disease by keeping patients from seeking medical care, activists warn.

His over 40-year battle against Hansen’s Disease has led Sasakawa to the conclusion that it is crucial to fight against the stigma which is still rife in society.

He pressed the United Nations General Assembly to adopt in 2010 the Resolution for the Elimination of Discrimination against Persons Affected by Leprosy and their Families.

He said these attitudes and beliefs no longer make sense in the light of science, but persist nonetheless.

Treatment making isolation for patients unnecessary in order to avoid contagion has been available since the 1940s, but forced isolation in leprosariums and leper colonies officially continued in a number of countries for decades.

In Brazil, forced segregation officially lasted until 1976 and in practice until the following decade.

With multi-drug treatment or polychemotherapy, introduced in Brazil in 1982, the cure became faster and more effective.

Information is key to overcoming the problems surrounding this disease, according to Socorro Gross, the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO) representative in Brazil who also held meetings with the Nippon Foundation delegation.

“Communication is essential, the media has a decisive role to play” to ward off atavistic fears and to clarify that there is a sure cure for Hansen’s Disease, that it is not very contagious and that it ceases to be so shortly after a patient begins to receive treatment, Gross, a Costa Rican doctor with more than 30 years of experience with PAHO in several Latin American countries, told IPS.