Civil Society, Featured, Gender, Gender Violence, Global, Headlines, Health, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, Poverty & SDGs, TerraViva United Nations, Women’s Health

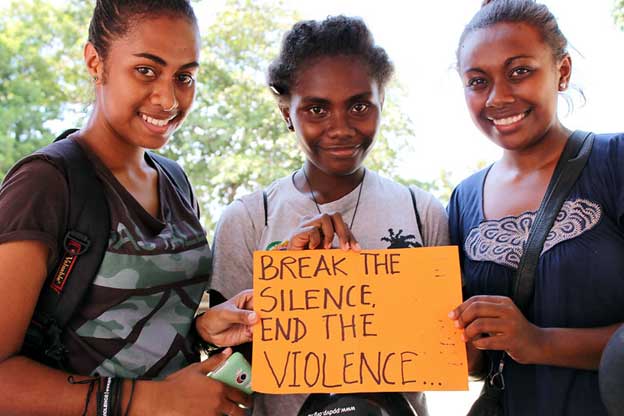

Testing new approaches for preventing gender-based violence to galvanize more and new partners and resources. Credit: UN Women

– How are the multiple shocks and crises the world is facing changing how we respond to gender-based violence? Almost three years after the COVID-19 pandemic triggered high levels of violence against women and girls, the recent Sexual Violence Research Initiative Forum 2022 (SVRI) shed some light on the best ways forward.

Bringing together over 1,000 researchers, practitioners, policymakers and activists in Cancún, Mexico, the forum highlighted new research on what works to stop and address one of the most widespread violations of human rights.

While some participants candidly – and bravely – shared that their initiatives did not have the intended impact, many discussed efforts that transformed lives, in big and small ways.

After 5 days of the forum one thing was clear; a lack of evidence is not what is standing in the way of achieving a better future. It is a lack of opportunities and the will to apply that evidence.

Among the many shared findings, UNDP presented its own evidence.

Since 2018, the global project on Ending Gender-based Violence and Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a partnership between UNDP and the Republic of Korea, and in collaboration with United Nations University International Institute for Global Health, has tested new approaches for preventing and addressing gender-based violence, to galvanize more and new partners, resources, and support to move from rhetoric to action.

Three key strategies have emerged.

1. We need to integrate

Gender-based violence (GBV) intersects with all areas of sustainable development. That means that every development initiative provides a chance to address the causes of violence and to transform harmful social norms that not only put women disproportionately at risk for violence, but also limit progress.

Bringing together diverse partners to jointly incorporate efforts to end GBV into “non-GBV” programmes has been central to the Ending GBV and Achieving the SDGs project. Pilots in Indonesia, Peru and the Republic of Moldova integrated a GBV lens into local development planning.

The results were local action plans that focused on needs and solutions identified by the communities themselves, including evidence-based GBV prevention programming such as the Common Elements Treatment Approach, which has been proven to reduce violence along with risk factors such as alcohol abuse. This approach is growing, opening up new and more spaces for this work.

2. We need to elevate

While evidence is crucial to creating change, the work doesn’t stop there. We also need to elevate this evidence to policy makers and to support them in putting the findings into action. In our global project, we went about this in different ways.

In Peru women’s rights advocates and the local government worked together to draft a local action plan to address drivers of violence in the community of Villa El Salvador (VES). By working collaboratively and building trust between key players, the project was able to take a more holistic approach and to create stronger alliances to boost its sustainability and impacts.

In particular, the local action plan was informed by cost analysis research that showed that this approach would pay for itself if it prevented violence for only 0.6 percent of the 80,000-plus women in VES who are at risk for violence every year.

Since the pilot’s launch, more than 15 other local governments have expressed interest in the model, and it has already been replicated in three.

3. We need to finance

Less than 1 percent of bilateral official development assistance (ODA) and philanthropic funding is given to prevent and address GBV, despite the fact that roughly a third of women have experienced physical or sexual violence.

The “Imperative to Invest” study, funded by the EU-UN Spotlight Initiative and presented at the SVRI Forum, shows just what can be achieved with a US$500 million investment. The study highlights that Spotlight’s efforts will have prevented 21 million women and girls from experiencing violence by 2025.

The Ending GBV and Achieving the SDGs project also finds positive results when financing local plans. Through pilot initiatives in Peru, Moldova and Indonesia, it was possible to mobilize funds when different municipal governments take ownership of participatory planning processes at an early stage.

The local level is a key, yet an often overlooked, entry point to identifying community needs and, through participatory, multi-sectoral partnerships, to translate them into funded solutions.

In Moldova the regional government of Gagauzia assigned funds to create the region’s first safe space, with the support of the community.

The SVRI Forum was living proof that a better future is possible. It offered profound moments for thoughtful exchange, learning with partners and peers, and deepened our own reflections on the outcomes and next steps for this global project.

As we approach the final countdown to meeting the SDGs, including SDG5.2 on eliminating violence against women and girls, it has never been more urgent to take all this evidence and turn it into action against gender-based violence. Let’s act today.

Jacqui Stevenson is Research Consultant UNU International Institute for Global Health, Jessica Zimerman is Project Specialist, Gender-based Violence, UNDP, and Diego Antoni is Policy Specialist Gender, Governance and Recovery, UNDP.

Source: UNDP

IPS UN Bureau