LILONGWE-(MaraviPost)-The National Advocacy Platform (NAP) has hailed the latest State of the Nation Address (SONA) as a bold and reassuring declaration of intent on governance, particularly in the fight against corruption.

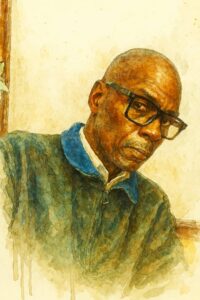

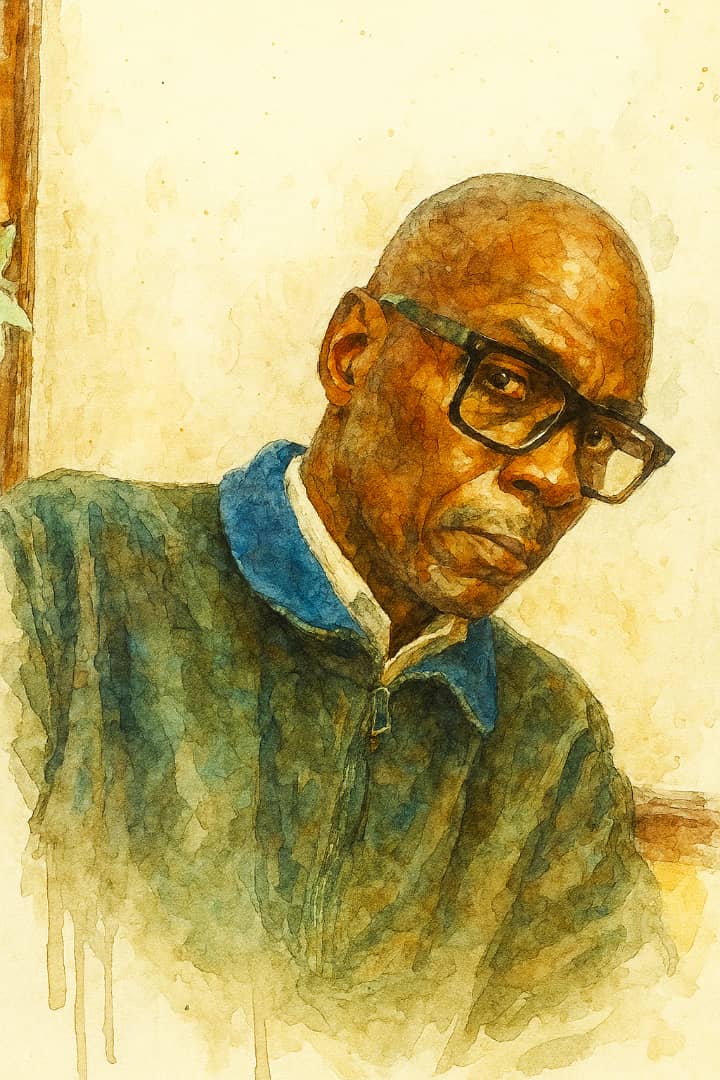

Speaking after the address, NAP Executive Director, Benedicto Kondowe, described the President’s message as a strong signal that government is ready to confront long standing governance challenges head on.

Kondowe said the President’s firm declaration that there will be no “sacred cows” in the fight against corruption demonstrates a renewed commitment to transparency, accountability and the rule of law.

He observed that corruption has for years eroded public trust in state institutions, weakened service delivery systems and slowed down Malawi’s national development agenda.

According to Kondowe, the President’s stance comes at a critical time when citizens are demanding decisive leadership and practical solutions to governance failures.

He further welcomed the President’s appeal to the three arms of government to act in the national interest, describing it as a reaffirmation of constitutional accountability and institutional responsibility.

Kondowe stressed that effective governance depends not only on powerful speeches but also on consistent, fair and impartial enforcement of the law, regardless of political affiliation or social standing.

He said if backed by genuine political will, the President’s approach could significantly rebuild public confidence and strengthen democratic institutions.

“Malawians want to see institutions empowered to act without fear or favour. That is the true test of commitment,” Kondowe emphasized.

He also underscored the importance of adequately resourcing and protecting anti corruption bodies from political interference to ensure their independence and effectiveness.

Kondowe noted that strong oversight institutions are essential for preventing abuse of power and ensuring public resources are used responsibly.

He added that improving governance systems will not only curb corruption but also create a stable environment for economic growth, investment and improved public service delivery.

NAP urged the government to translate its promises into measurable action, saying citizens are eager to witness tangible results in the ongoing fight against corruption.