So on Wednesday night, I was a guest on the radio programme Indaba. You know the programme that discusses issues relevant to raising African-centred consciousness? No?

The one that was once two hours but is now reduced to one because, let’s be honest, it’s not like there’s any issue about Black hen chicken too complex or serious that can’t be reduced to sound bites in between Play Whe gambling results.

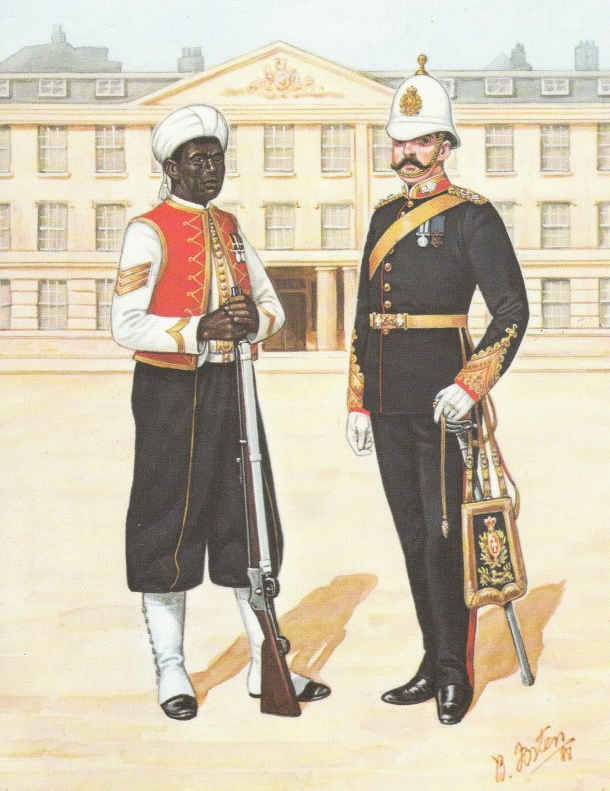

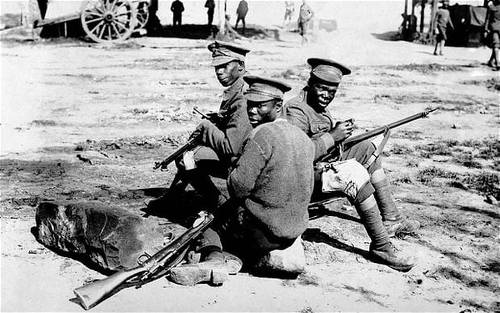

Anyway… So I was being interviewed regarding some sentiments I expressed on Armistice/Memorial Day and the experiences of West Indian troops “of colour” who served in the British West India Regiment in World War I.

(Copyright UK Guardian)

As you know this marks the 100th year since the ending of that ‘war to end all wars’ on the 11 day of the 11th month, 1918… Oh f**k wait; yuh didn’t know that neither?

See de same thing I saying. Every year on the 11/11, it does have a big fancy parade with even fancier speeches, prayers and sentiments about those who ‘gave’ their lives ‘unselfishly’ for their country and for freedom.

Don’t think for one moment I’m mocking or trivialising those men and women who served and fought in some of history’s major wars; the blood of the military runs through my family and one of my great-uncles was in WWII. Many vets from the West Indies served admirably against huge adversities and did much through individual acts to earn some degree of dignity and respect for all of us.

But as people who live in a region that has been exploited by major powers and used as a political and military football—not to mention Uncle Sam’s backyard—we really should be more enquiring about what narratives we are made to accept.

We should also be very wary of how we laud events that glorify the ‘spilling of the red wine of youth’.

We should be more analytical about these wars our forbears were drawn into so as to get a clear understanding of our own issues today, how those past events connect to ours and how certain things like the manipulation of emotion through propaganda are still being used to tie up we head with the same rationale.

Unless.

You’re already sold on the Kool-Aid that those major European civil wars—aka World Wars I and II—really had much to do with defending freedom, democracy and ending tyranny. Dais ‘chain-up’ talk dred.

You’d think we in the Caribbean had gotten wise to that by now—but then if a bright QRC man could say there is no evidence connecting racism to colonialism and a big UWI man could ask if it wasn’t for Columbus, slavery and colonialism bringing us here, where would we be today; it’s clear now why that same UWI had to hold a conference on critical thinking.

Because, you see, those two major bloodbaths—and the many other ‘minor’ ones—had almost everything to do with racist imperial powers, particularly England, warring over raw materials, mineral resources and geographic positioning they felt somehow entitled to possess; and at the expense of other racist, imperial powers.

Our forbears were encouraged to enlist to ‘defend’ king, country and freedoms they themselves didn’t even have and the British had absolutely no intentions of giving. That same freedom from tyranny talk is the myth we too in 2018 are being told via our history books and popular media. But then, it’s been said that if you tell a lie often enough, many people—hell, even you—will believe you.

This particular lie is constructed around what Prof Terry Boardman calls HERE the myth of St George.

St George, according to legend, rescued a princess from an evil dragon. This myth has been reproduced over and over and over and applied in real political terms, and not always as subtle or coded as the “dog whistle politics” Prof Ian H Lopez speaks about in his works HERE.

Back in 1914 (and 1939) Britain and its allies were portrayed as St George, Belgium as the princess and Germany as the evil dragon. Today, the West is St George, brown women in Islamic countries as the princess and radical Islam as the dragon.

It wasn’t hard to believe the lie; at least three centuries of enslavement, colonial rule, colonised schooling and churching ensured that a substantial number of colonial subjects truly believed they were full-fledged British citizens.

In plantation societies where violence and aggression was the norm and militarism was considered the ultimate avenue for a real man to prove himself, thousands of young, unemployed and under-employed men—living in squalid conditions held over from enslavement or created because vagrancy laws forced them back to sugar, cocoa and coffee estates—were only too eager to enlist, finally prove themselves in battle and earn not just respect, but gratitude that they hoped would extend to greater political autonomy.

This is why, for instance, even Marcus Garvey—and WEB duBois on the African-American side—lent support to the war effort.

Of course that meant that the British propaganda machine had to hide the fact that by 1914, the British alone had militarily intervened in almost every part of the globe in the unending search for resources. They had long since invaded India and were busily under-developing it; in 1898 they invaded the Sudan, committing horrible atrocities in the process.

Then during the Boer War they fought the Dutch settler-colonials in South Africa so as to take control of gold and diamonds—so one set of racist imperialists took from another set of racists in order to deny access to a third set of racist imperialists, the Germans.

In 1900, Britain, along with other Western powers and the United States, had already militarily intervened in China. In 1904, it invaded Tibet, killing over 2000 people.

Additionally, in their own country, women were denied the right to vote and imprisoned hunger-striking feminist activists were being force-fed. Further back, in 1819, the British government brutally put down a peaceful gathering for representation in Parliament, in what was known as the Peterloo Massacre. So a free, democratic country it was most certainly not.

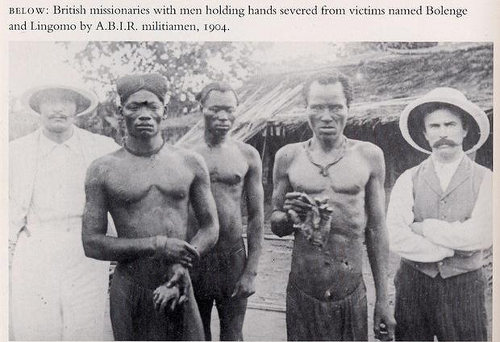

Oh by the way, the then ‘princess’, Belgium, was in the news for quite a while prior because of the horrific atrocities people like King Leopold were committing in its colony of the Congo. Beatings and amputations were a daily occurrence; women and children were held hostage as labourers were sent deeper and deeper into forests in search of rubber trees.

An estimated 10 million Congolese were killed and many more mutilated for not making their quotas of rubber sap. Belgium’s wealth and standard of living today owes much to that period. Remember that next time you purchase their chocolates.

Even more importantly, the evidence had to be concealed from the colonials—and poor white English working classes who were also spurred to fight to defend freedom—that far from being the defenders, the British had been planning to wage war against Germany since the 1880s.

The Saturday Review, a most respected journal at the time, informs us through an article printed in 1897 that:

“[I]n Europe, there are two great, irreconcilable forces, two great nations who would make the whole world their province, and who would levy from it the tribute of commerce. England with her long history of successful aggression, with her marvelous conviction that in pursuing her own interests she is spreading light among nations dwelling in darkness, and Germany, bone of the same bone, blood of the same blood, with a lesser will-force… compete in every corner of the globe

“[…] Is there a mine to exploit, a railway to build, a native to convert from breadfruit to tinned meat… the German and the Englishman are struggling to be first.”

At least three different articles of this nature can be found in this journal, at least one of which ended with “Germania est delenda” (Germany must be destroyed).

And as if that wasn’t bad enough, Britain had also developed plans to go to war with the United States, all in the name of who gets to control the mineral resources of the global south—the peoples who lived there were of no importance whatsoever outside of being fit to labour for the Euro and, as the above passage shows, a market for European tinned food products. Doesn’t all this sound kinda familiar?

So, if we’re really serious about honouring the legacy of our West Indian veterans, let us stop mindlessly following traditions we were saddled with in 1962 and start thinking with our own minds.

We can start by understanding that aside from the obvious money factor, the vets of WWI and II who came out of poor labouring class communities were seeking to gain respect from a people who saw—and still see—no need to give any.

Having understood that, we must then set about examining the worldview of those who colonised us in order to make connections between how those of generations gone saw us and how their descendants still see us, such as the Clintons, Trumps, Kochs, Buchanans, Macrons, Blairs, and Mays.

Don’t be wasting time debating whether or not I have some anti-white, anti-Western chip on my shoulder. Discuss instead how poor, labouring class West Indians had to fight for the right to prove their manhood in the rigid confines of a racist, classist imperialist structure of power that took it away.

Discuss how almost all of them had that ‘right’ to fight denied because on the one hand ‘respected’ academic journals stressed that black people didn’t possess the ‘moral fibre’ to fight, while on the other hand other ‘authoritative’ theories warned against blacks being allowed to shoot and kill white men.

(Copyright UK Guardian)

Discuss how there were two regiments because local whites refused to fight with—and certainly not take orders from—black soldiers. Discuss what was mentioned in Glenford Howe’s fascinating book “Race, War and Nationalism: A Social History of West Indians in the First World War” in which German prisoners of war were kept in a heated room while black BWIR troops were shivering in an unheated room in the same building.

You’ll also have to explain how, even though Britain were supposedly mortal enemies—the war having been underway since 1914—it deployed troops in 1915 to what is now Malawi to help German settlers put down an African nationalist uprising under John Chilembwe.

The real stories behind the two world wars are signposts to almost identical issues today. The contest today is exactly what it was prior to 1914 and 1939, which is control of the mineral resources.

The role people of colour had to play then is not that much different from what they are expected to play now. And although many are now in political and financial positions their forbears of 1914 could scarcely dream about, they’re still ‘niggers’, ‘wetbacks’, ‘coolies’, ‘ragheads’, ‘spics’ and so on.

Indeed, it’s deepening now with the resurgence of Far Right and centrist liberal politics. The myth of St George is as strong today as it has ever been in previous generations.

Fortunately, there are many Princesses who can now speak for themselves. Many of them are under no illusions about St George and his motives.

So if they can possess the independence of mind to speak for themselves, the least we can do is to tell the story of our heroes from our own perspective for a change.