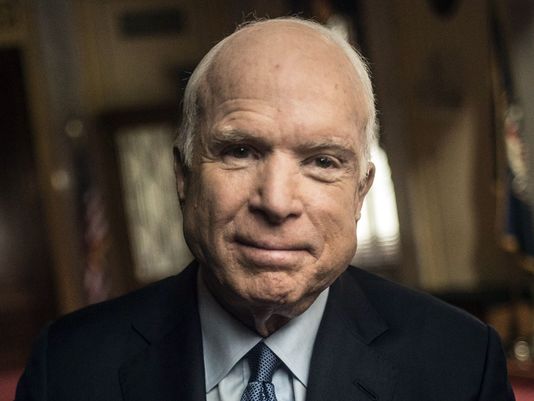

U.S. Sen. John S. McCain, the son and grandson of four-star admirals, was bred for combat. He endured more than five years of imprisonment and torture by the North Vietnamese as a young naval officer and went on to battle foes on the left and the right in Washington, driven throughout by a code of honor that both defined and haunted him.

Sen. McCain, 81, died Aug. 25 at his ranch near Sedona, Ariz., his office announced in a statement. The senator was diagnosed last year with a brain tumor, and his family announced this week that he was discontinuing medical treatment.

During three decades of representing Arizona in the Senate, he ran twice unsuccessfully for president. He lost a bitter primary campaign to George W. Bush and the Republican establishment in 2000. He then came back to win the nomination in 2008, only to be defeated in the general election by Barack Obama, a charismatic Illinois Democrat who had served less than one term as a senator.

A man who seemed his truest self when outraged, Sen. McCain reveled in going up against orthodoxy. The word “maverick” practically became a part of his name.

Sen. McCain regularly struck at the canons of his party. He ran against the GOP grain by advocating campaign finance reform, liberalized immigration laws and a ban on the CIA’s use of “enhanced interrogation techniques” — widely condemned as torture — against terrorism suspects.

To win his most recent reelection battle in 2016, for a sixth term, he positioned himself as a more conventional Republican, unsettling many in his political fan base. But in the era of President Trump, he again became an outlier.

The terms of engagement between the two had been defined shortly after Trump became a presidential candidate and Sen. McCain commented that the celebrity real estate magnate had “fired up the crazies.” At a rally in July 2015, Trump — who avoided the Vietnam draft with five deferments — spoke scornfully of Sen. McCain’s military bona fides: “He was a war hero because he was captured. I like people who weren’t captured.”

Once Trump was in office, Sen. McCain was among his most vocal Republican critics, saying that the president had weakened the United States’ standing in the world. He also warned that the spreading investigation over Trump’s ties to Russia was “reaching the point where it’s of Watergate-size and scale.”

Sen. McCain’s most dramatic break with Trump came nine days after the Arizona senator announced on July 19, 2017, that he had been diagnosed with brain cancer. He returned to the Senate chamber, an incision from surgery still fresh above his left eye, and turned thumbs down on a GOP plan to replace the Affordable Care Act. Sen. McCain’s no vote, along with those of two other Republicans, sent his party’s signature legislative goal hurtling toward oblivion.

In both of his own presidential races, Sen. McCain had dubbed his campaign bus the “Straight Talk Express.” To the delight of reporters who traveled with him in 2000, he was accessible and unfiltered, a scrappy underdog who delighted in upsetting the Republican order.

“He was always ready for the next experience, the next fight. Not just ready, but impatient for it,” said his longtime aide Mark Salter, who co-authored more than a half-dozen books with the senator, including three memoirs, the final of which included a stinging critique of Trump. “He took enjoyment from fighting, not winning or losing, as long as he believed he was fighting for a cause worth the trouble.”

So broad and party-bending was his appeal that Senate Democrats in 2001 quietly tried to persuade him to become one of them. In 2004, Democratic presidential nominee John F. Kerry, a Senate colleague who later became Obama’s secretary of state, considered offering Sen. McCain the second spot on his ticket.

Sen. McCain’s 2008 presidential campaign turned out to be a far more conventional operation than his first bid for the White House. He stuck to his talking points and came to represent the status quo that he had once promised to topple.

rom there, he headed to Pensacola, Fla., to be trained as a Navy pilot and continue the rowdy existence of his days at the academy.

One girlfriend at the time was a stripper who went by the professional name Marie, the Flame of Florida. Sen. McCain recalled taking her as his date to a party of young officers and their mannerly wives. Marie became bored, drew a switchblade from her purse, popped it open and cleaned her fingernails.

He did a stint as a flight instructor in Meridian, Miss., at McCain Field, named for his grandfather. It was there, Sen. McCain recalled, that he matured and became dedicated to distinguishing himself as a pilot.

“As a boy and young man, I may have pretended not to be affected by the family history, but my studied indifference was a transparent mask to those who knew me well,” the senator wrote in a 1999 memoir of his early life, “Faith of My Fathers,” co-authored by Salter. “As it was for my forebears, my family’s history was my pride.”

Sen. McCain also became involved in a serious romance, with Carol Shepp of Philadelphia, whom he had known since his days at the academy. They wed in July 1965, and he soon adopted her two sons from a previous marriage, Douglas and Andrew. The couple later had a daughter, Sidney.

Sen. McCain requested and got orders to do a Vietnam combat tour, joining a squadron on the supercarrier Forrestal in the Tonkin Gulf. On July 29, 1967, having flown five uneventful bombing runs over North Vietnam, he was preparing for takeoff when a missile accidentally fired from a nearby fighter struck the fuel tank of his A-4 Skyhawk, Sen. McCain wrote in his memoir. It set off explosions and a fire that killed 134 crewmen, destroyed more than 20 planes and disabled the ship so severely that it took two years to repair.

His own injuries being relatively — and miraculously — minor, Sen. McCain, then a lieutenant commander, volunteered for dangerous duty on the undermanned carrier Oriskany. He joined a squadron nicknamed the Saints that was known for its daring; that year, one-third of its pilots would be killed or captured.

Brutal captivity

On Oct. 26, 1967, Sen. McCain was on his 23rd mission and his first attack on the enemy capital, Hanoi. He dove his A-4 on a thermal power plant near a lake in the center of the city.

As he released his bombs on the target, a Russian-made missile the size of a telephone pole blew off his right wing. The lieutenant commander pulled his ejection-seat handle and was knocked unconscious by the force as he was hurled from the plane. He came to when he hit the lake, where a mob of Vietnamese had gathered.

With both arms and his right knee broken, he was dragged from the lake, beaten with a rifle butt and stabbed in the foot with a bayonet. Then Sen. McCain was taken to the French-built prison that American POWs had dubbed the “Hanoi Hilton.”

So began 5½ years of torture and imprisonment, nearly half of it spent in solitary confinement. During that time, his only means of communicating with other prisoners was by tapping out the alphabet through the walls.

At first, his family was told that he was probably dead. The front page of the New York Times carried a headline: Adm. McCain’s Son, Forrestal Survivor, Is Missing in Raid.

The North Vietnamese, however, perceived that there was propaganda value in the prisoner. They called him the “crown prince” and assigned a cellmate to nurse him back to health. As brutal as his treatment was, Sen. McCain later said, prisoners who lacked his celebrity endured worse.

Shortly before his father assumed command of the war in the Pacific in 1968, Sen. McCain was offered early release. He refused because it would have been a violation of the Navy code of conduct, which prohibited him from accepting freedom before those who had been held longer.

“I knew that every prisoner the Vietnamese tried to break, those who had arrived before me and those who would come after me, would be taunted with the story of how an admiral’s son had gone home early, a lucky beneficiary of America’s class-conscious society,” Sen. McCain recalled. “I knew that my release would add to the suffering of men who were already straining to keep faith with their country.”

His lowest point came after extensive beatings that broke his left arm again and cracked his ribs. Ultimately, he agreed to sign a vague, stilted confession that said he had committed what his captors called “black crimes.”

“I still wince when I recall wondering if my father had heard of my disgrace,” Sen. McCain wrote. “The Vietnamese had broken the prisoner they called the ‘Crown Prince,’ and I knew they had done it to hurt the man they believed to be a king.”

In March 1973, nearly two months after the Paris peace accords were signed, Sen. McCain and the other prisoners were released in four increments, in the order in which they had been captured. He was 36 years old and emaciated.

The effects of his injuries lingered for the rest of his life: Sen. McCain was unable to lift his arms enough to comb his own prematurely gray hair, could only shrug off his suit jacket and walked with a stiff-legged gait.

Entering politics

Sen. McCain had hoped to remain in the Navy, but it became clear that his disabilities would limit his prospects for advancement.

In the meantime, he found himself drawn toward the civilian world of politics — and it toward him. Hobbling on crutches in his dress-white service uniform, he shook President Richard M. Nixon’s hand. Sen. McCain also struck up a friendship with then-California Gov. Ronald Reagan, who invited the former POW to speak at an annual prayer breakfast in Sacramento.

He developed a network of political contacts while working in the Navy’s legislative affairs operation in the late 1970s. His office on the first floor of the Russell Senate Office Building was a popular late-afternoon socializing spot for younger senators and their staffs.

Sen. McCain’s marriage, meanwhile, frayed and fell apart. That was not an unusual story among returning Vietnam POWs, and in his case, the dissolution was aggravated by his infidelities.

While he and his wife were separated, Sen. McCain visited Hawaii, where he met Cindy Hensley, the daughter of a wealthy Arizona beer distributor. A few months after his divorce became final in 1980, he married Hensley. Then-Sen. William S. Cohen (R-Maine), later to be a defense secretary, was his best man, and then-Sen. Gary Hart (D-Colo.), a future presidential contender, was an usher.

The couple had three children: Meghan McCain, who became a media personality and blogger, and sons Jimmy McCain and Jack McCain, both of whom served in the military. They also adopted a daughter, Bridget McCain, whom Cindy had met while visiting an orphanage in Bangladesh.

Besides his mother, his wife and seven children, survivors include a brother, Joseph P. McCain of Washington; a sister, Jean McCain Morgan of Annapolis; and five grandchildren.

Sen. McCain retired from the Navy at the rank of captain and moved to Arizona in 1981, with an eye toward running for Congress. The opportunity presented itself the following January when a longtime Republican congressman, John Rhodes, announced his retirement. That same day, the McCains bought a house in Rhodes’s Phoenix district, and John McCain was soon in a race against three other candidates.

He was called an opportunist and a carpetbagger — accusations he dispatched with a single answer at a candidate forum.

“I wish I could have had the luxury, like you, of growing up and spending my entire life in a nice place like the 1st District of Arizona, but I was doing other things,” he replied to one critic. “As a matter of fact, when I think about it now, the place I lived longest in my life was Hanoi.”

He won the primary by six points and breezed through the general election. Four years later, in 1986, he was elected in a landslide to the Senate, replacing the retiring Barry Goldwater, one of the most influential conservative politicians of the 20th century.

John McCain was a Capitol Hill celebrity from the moment he was elected to the House.

In many areas, he was a reliably conservative voice and vote. But from the beginning, he showed what became a trademark streak of independence. He called for the withdrawal of Marines from Lebanon in 1983 after a terrorist bombing left 241 U.S. service members dead; he voted to override President Reagan’s veto of sanctions against the apartheid regime of South Africa in 1986.

And — surprisingly to many — as a member of the Senate, he worked to normalize relations with Vietnam.

Sen. McCain crusaded against pork-barrel spending, the practice by which lawmakers direct taxpayer money to projects in their districts. He was also the only Republican to vote against the Telecommunications Act of 1996, a deregulation measure he said had been “written by every [special] interest in the world except the consumers.”

Acclaimed by the media, he was not popular in the Senate. Many of his colleagues were put off by his certitude.

“John puts things in terms of black and white, right and wrong,” then-Sen. Tim Hutchinson (R-Ark.) told The Washington Post in 2000. “If you disagree with him, you’re wrong. He doesn’t see that there could be legitimate differences of opinion that deserve respect.”

One of the greatest setbacks for Sen. McCain, who had styled himself an idealist and a reformer, came in 1989, when his name became associated with a scandal. He and four other senators — all Democrats — were accused of trying to pressure federal bank regulators to back off an investigation of Charles H. Keating Jr., a high-living Arizona businessman whose savings and loan collapsed and cost taxpayers more than $3 billion.

Over the years, Keating had contributed heavily to Sen. McCain’s House and Senate campaigns. The senator’s family had taken at least nine trips, at Keating’s expense, to the Bahamas, where Keating had a luxurious vacation estate.

Sen. McCain and the four Democrats — Alan Cranston of California, Dennis DeConcini of Arizona, John Glenn of Ohio and Donald W. Riegle Jr. of Michigan, all of whom had also benefited from Keating’s largesse — became known as the “Keating Five.”

The Senate Ethics Committee finally determined that Sen. McCain had not done anything more serious than showing “poor judgment” by attending two meetings with the regulators and the four other senators. It was the lightest reprimand the committee gave in connection with the scandal. The others were rebuked but were not charged with crimes.

Sen. McCain felt that he bore a permanent taint. “It will be on my tombstone, something that will always be with me, something that will always be in my biography,” he said, “and deservedly so.”

The experience also lit the fire for what would become his signature issue and biggest legislative achievement: an overhaul of campaign finance laws. Sen. McCain teamed up with one of the Senate’s most liberal members, Russell Feingold (D-Wis.), to author a measure that called for the most dramatic change to the system since the post-Watergate reforms of 1974.

It took them more than seven years to get the legislation through. The 2002 law’s main thrust was to ban unlimited, unregulated “soft money” donations to parties, which were used as a means of skirting the contribution limits to individual candidates.

In less than a decade, however, the Supreme Court’s Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision opened the money floodgate and led to the rise of super PACs, which can spend unlimited sums, as long as they do not coordinate directly with candidates. Sen. McCain called it “the worst decision of the United States Supreme Court in the 21st century.”

Presidential campaigns

When Sen. McCain announced in September 1999 that he was running for the Republican nomination for president, it was yet another assault on the political establishment, which had put its chips on then-Texas Gov. Bush, the son of a former president.

“In truth, I had had the ambition for a long time. It had been a vague aspiration,” he later wrote. “It had been there, in the back of my mind, for years, as if it were simply a symptom of my natural restlessness. Life is forward motion for me.”

He ran as a truth-telling reformer, held a record-setting 114 town hall meetings in New Hampshire (while effectively ignoring the Iowa caucuses) and pulled off a stunning 18-point victory over Bush in the Granite State’s first-in-the-nation primary. But his campaign ran aground in South Carolina in what came to be regarded as the nastiest primary in memory.

Sen. McCain was the target of rumors: that he had fathered a black child (twisting the facts about his dark-skinned adopted daughter); that his wife had a drug habit (she acknowledged having been addicted to painkillers and stealing them from a charity she ran); that his years as a POW had left him brainwashed and insane.

One of his regrets, he later said, was getting tangled up in South Carolina’s emotional debate over flying the Confederate flag at the capitol in Columbia. After describing the banner as “a symbol of racism and slavery,” Sen. McCain bowed to the pleas of his panicked strategists and issued a statement saying he could “understand both sides” of the question.

Later, he wrote that he regretted not having told the truth, which was that he believed “the flag should be lowered forever from the staff atop South Carolina’s capitol.”

“I had not been just dishonest. I had been a coward, and I had severed my own interests from my country’s. That was what made the lie unforgivable,” he recalled. “All my heroes, fictional and real, would have been ashamed of me.”

Bush handily defeated Sen. McCain in South Carolina, beginning the end of the senator’s insurgent campaign. In April, a month after he dropped out of the 2000 race, Sen. McCain returned to the state and publicly apologized for having chosen “to compromise my principles. I broke my promise to always tell the truth.”

The bitterness of that campaign lingered for much of Bush’s presidency. Sen. McCain was, for instance, one of only two Senate Republicans to vote against Bush’s 2001 tax cuts. He said they were fiscally irresponsible and benefited “the most fortunate among us, at the expense of middle-class Americans who most need tax relief.”

But by the time he ran again in 2008, Sen. McCain had come to terms with Bush and the Republican Party, and they with him. He not only voted to extend the tax cuts in 2006, but also advocated making them permanent.

Whereas Sen. McCain had lashed out at evangelical leaders Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell as “agents of intolerance” during his first presidential bid, he delivered the commencement address at Falwell’s Liberty University in 2006. Falwell introduced him with lavish praise, saying, “The ilk of John McCain is very scarce, very small.”

The shift rightward caused a breach with a constituency that Sen. McCain had long counted as in his corner: the media.

“Are you going into crazy base world?” comedian Jon Stewart asked Sen. McCain during an appearance on Comedy Central’s “The Daily Show” a few weeks before the speech at Liberty.

“I’m afraid so,” Sen. McCain deadpanned.

His campaign all but collapsed in the summer of 2007, but Sen. McCain battled back and won the nomination.

Still, he was flying into head winds in the general election. The war in Iraq, which he had supported, was unpopular, as was the Republican incumbent in the White House. Palin’s erratic, unprepared performance became a story in itself.

Most important, he was up against a Democrat who seemed tailor-made for that moment in history: Obama was better financed, ran a better campaign, had opposed the Iraq War and offered the captivating prospect of putting an African American in the White House for the first time.

Nonetheless, the race looked as if it could be close until the final weeks, when the financial system went into a meltdown. Sen. McCain, so sure of himself on national security issues, seemed less than savvy at handling economic ones. Even as the crash was building into the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, the senator declared that “the fundamentals of our economy are strong.”

Returning to Congress, Sen. McCain became a frequent antagonist of the man who had defeated him for president. He contended for instance that Russian President Vladimir Putin’s 2014 invasion of Crimea was a result of “a feckless foreign policy where nobody believes in America’s strength anymore.”

When Sen. McCain got the gavel of the Armed Services Committee in 2015, he told The Post that he was having more fun than at any time since his 2000 presidential campaign. That same year, he announced plans to run for a sixth term in the Senate.

Sen. McCain won handily, and in his victory speech to supporters, he predicted that campaign “might be the last.”

“Thank you one last time,” he added, “for making me the luckiest guy I know.”

In his final book, reflecting on his life as it came to an end, McCain wrote: “It’s been quite a ride. I’ve known great passions, seen amazing wonders, fought in a war, and helped make a peace. I made a small place for myself in the story of America and the history of my times.”