The ranks of diplomats gathered in Paris during the spring of 1919 included a most unusual member of the British imperial delegation: a youthful South African politician and general named Jan Christiaan Smuts. One of his country’s founding figures and a leading force behind the formation of the British Commonwealth, the League of Nations and the United Nations, Smuts helped shape the emergence of the post-World War II liberal order — even though, all the while, he helped craft segregationist white rule in South Africa. How did he reconcile his promotion of human rights abroad and suppression of them at home? And how should we weigh this complicated, flawed but important figure, a century later?

Smuts carefully cultivated a persona as a warrior, statesman and philosopher. As a leader of the Dominion of South Africa, he was a signatory to the peace at Versailles. He was also a veteran of the Boer War who, while operating on horseback behind British lines, carried a copy of Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason” and the New Testament (in Greek) in his saddlebag. Unlike many Afrikaner hard-liners, Smuts supported the process of reconciliation with the victorious British, and he succeeded in turning military defeat into political success: He was the principal architect of the unified South Africa which came into existence as an independent nation in 1910.

This compact was threatened at the outbreak of war in 1914 when a group of Afrikaner militants, seeking to avenge the loss of the Boer republics, joined forces with Germans in South West Africa in an attempt to overthrow the South African government. Smuts supported his Boer War compatriot, Prime Minister Louis Botha, who put down the insurrection at home and initiated a series of daring raids into South West Africa in 1915. The German colonial forces surrendered in July, a notable early victory for the Allies in the first world war.

Later in 1915 Smuts led a grueling military campaign in German-held East Africa, an area twice the size of Germany, which resulted in the end of German rule, and with it the kaiser’s hopes of uniting his country’s holdings on the Atlantic and Indian Oceans to create a colonial “Mittelafrika.” Smuts’s rapid success changed African colonial history and connected South Africa with other British settler colonies in Africa.

With the defeat of Germany in Africa, Smuts proceeded to London, where a conference of representatives from the British Empire had gathered to support the war effort and give shape to an emergent commonwealth that would review the terms of imperial membership. Smuts, his reputation burnished on the battlefield, was well-placed to guide that process. In May 1917, addressing both houses of the British Parliament, he made the case for a commonwealth as “a dynamic, evolving system of states and communities under a common flag.” This definition recognized the growing pressure from the imperial white dominions — like South Africa — that the commonwealth should not be dominated by Britain, but should coexist as a group of equals committed to a higher cause. As the historian Mark Mazower has shown, this idea for the Commonwealth served as a model for “an even larger future political community,” a League of Nations.

Jan Smuts fought the British in the Boer War. Fifteen years later, he was a member of Lloyd George’s Cabinet.

Smuts was by now a close ally of Prime Minister Lloyd George of Britain, who invited him to join the British War Cabinet. He quickly became Indispensable. He drew up plans for an integrated Air Ministry, resulting in the creation of the Royal Air Force. Acting on Lloyd George’s behalf, he intervened on the question of home rule in Ireland, where his standing as an opponent of British imperialism gave him special leverage. Smuts also used his outsider status to talk down angry Welsh coal miners in Tonypandy, reminding them that the Boer War was “a war of a small nation against the biggest nation in the world.” He sealed the loyalty of the miners by persuading them to sing: They answered with a rousing rendition of “Land of My Fathers.”

Smuts declined an invitation to lead the British wartime campaign against the Ottomans in Palestine. But he saw the geostrategic advantages of a Jewish homeland in proximity to the Suez Canal, and saw analogies between the nationalist aspirations of Jews and Boers, both of whom deserved “historic justice.” A close friend of Chaim Weizmann, Smuts played a considerable behind-the-scenes role in formulating the 1917 Balfour Declaration, in which Britain announced its support for a Jewish homeland. In 1919, he traveled to Budapest on behalf of the Foreign Office to meet with the Hungarian Communist leader Bela Kun in an effort to negotiate the military frontier between his country and Romania, regaling Kun with stories from the Boer War.

Britain was gratified by the way in which this former anti-imperial fighter transmuted into a loyal exponent of the Commonwealth and a willing supporter of the wartime government. Winston Churchill, who had been captured in South Africa while working as a journalist during the Boer War, was a lifelong admirer of Smuts, and relied heavily on his counsel during World War II. In 1917, Churchill welcomed Smuts to London in the most fulsome terms: “At this moment there arrives in England from the outer marches of the Empire a new and altogether extraordinary man.” But Smuts’s forays into international politics came at a cost. He was increasingly vilified at home by Afrikaner nationalists as the “handyman of the empire” — a term originally used as praise by British newspapers.

Along with his vital contribution to defining the Commonwealth, Smuts played an important part in conceiving of the League of Nations itself. Concerned about how to achieve long-term peace in Europe, and watchful about the threat of Bolshevism, he argued that the terms imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles were overly harsh: The same spirit of magnanimity — or “appeasement,” in Smuts’s words — that had achieved a workable peace between Britons and Boers ought now to be demonstrated in the case of German reparations. Smuts encouraged John Maynard Keynes to write his seminal critique of the treaty, “The Economic Consequences of the Peace,” and in 1918 wrote a proposal of his own: “The League of Nations: A Practical Suggestion.”

The ideas contained in this pamphlet envisioned the League as a means to fill the vacuum left by Europe’s broken empires. Smuts saw the Commonwealth as an “embryo league of nations because it is based on the true principles of national freedom and political decentralization.” In spare prose, Smuts topped his talents as a lawyer with a sprinkling of inspirational idealism, translating President Woodrow Wilson’s aspirational Fourteen Points into a workable instrument for a peace “founded in human ideals, in principles of freedom and equality, and in institutions which will for the future guarantee those principles against wanton assault.”

Lloyd George commended Smuts’s ideas. Wilson was enthused as well: He invited Smuts to his residence at the Hôtel Crillon in Paris in January 1919, and incorporated some of Smuts’s ideas in his own proposals for the League. Smuts and Botha were unable to persuade the Peace Conference to allow Germany’s former colonies in the Pacific and Africa — which Smuts caricatured as “inhabited by barbarians, who not only cannot possibly govern themselves” — to pass directly to New Zealand and South Africa. Still, the Boer generals got the next best thing: Under the League’s mandate system, in which it acted as the trustee for less “civilized” nations deemed not ready for independence (and which Smuts helped design), South Africa effectively took over South West Africa, governing until it finally gained its independence as Namibia in 1990.

Smuts’s approach to politics was shaped by, of all people, Walt Whitman. While studying for a law degree at Cambridge, he wrote a treatise, “Walt Whitman: A Study in the Evolution of Personality,” in which he argued that the American poet exemplified an expansive conception of freedom rooted in pantheism and human potential, rather than religiosity. Smuts went on to develop this approach as “holism,” which he outlined in another treatise: Evolution pushed humans and societies to join ever larger wholes, from small local units to nations and commonwealths, culminating in global forms of association like the League.

Smuts’s approach to politics was shaped by, of all people, Walt Whitman.

Smuts felt a different affinity with another famous American, Woodrow Wilson. In the latter stages of drafting the 1919 Treaty, Smuts was privately critical of Wilson, fearing that he was capitulating to those who wanted to punish Germany, and so endangering long-term peace in Europe. Yet when the president left office in 1921, much diminished in health and prestige, Smuts defended him, declaring the League of Nations “one of the great creative documents of human history.” Smuts and Wilson had much in common as intellectual statesmen. As high-minded Christians, both raised in rural societies shaped by slavery, they shared formative experiences. They were also inclined to moralizing white paternalism and an acceptance of racial segregation.

In arguing for peace and justice at Versailles, Smuts took no account of the delegation from the African National Congress, which petitioned the British government to help in pushing back against South Africa’s increasingly oppressive segregationist laws. In doing so, they made explicit reference to Wilsonian ideals. The delegation, ably led by Solomon Plaatje, gained an audience with a sympathetic Lloyd George, who referred their claims to Smuts. But Smuts did not meet with them, and dismissed their views as unrepresentative and exaggerated.

Still, Smuts could not avoid what he and others called “the native question,” especially when he returned to South Africa in 1919, becoming prime minister and minister of native affairs after Botha’s death that year. The experience of black African colonial troops in World War I — the discrimination they faced, versus the soaring promises of self-determination that came out of Versailles — had set off a wave of unrest and nationalist awareness across much of the continent. An American-trained Baptist preacher, John Chilembwe, led a revolt in Nyasaland (now Malawi) in 1915; it was put down, but Chilembwe’s martyrdom did much to encourage the development of nationalism in his country.

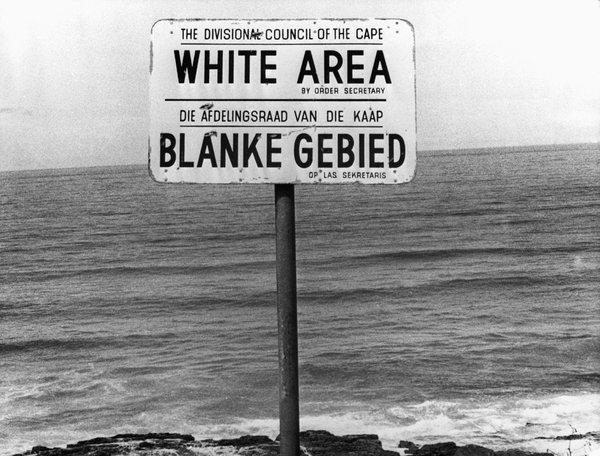

South Africa, with its white population intent on securing supremacy over its African, Indian and “colored” populations, was especially tense in the postwar years. White leaders, including Smuts’s government, were increasingly determined to institute comprehensive racial segregation; that, combined with a weakening economy, led to an upsurge of black militancy. Black sanitary workers, known as “bucket boys,” went on strike in 1918, followed by black mineworkers in 1920. At the Cape Town docks, Clements Kadalie founded the Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union in 1919. Through the 1920s, this organization spread rapidly in the countryside, spurred by millenarian hopes of black Americans coming to their aid.

As prime minister, Jan Smuts could not accept blacks as political equals seeking rights of citizenship. Throughout his career, he preferred to think of the “native problem” in abstract terms. Smuts relied on anthropological theory to justify segregation on the basis of fundamental cultural difference, and cited new fossil finds, pointing to South Africa’s singular importance in hominid evolution, to suggest that prehistoric differences between different races were profound and perhaps unbridgeable in the present. Smuts was nowhere as hard line as some of his white compatriots, but neither was he in favor of black political rights. Like many paternalistic and “moderate” whites, he was inclined to defer problems of race equality to the future.

That wasn’t always possible, and Smuts had little compunction about using the police and army to put down rebellions — white as well as black. In 1919, a self-declared Christian prophet, Enoch Mgijima, formed a community calling themselves the Israelites. Some 3,000 of his followers gravitated to the agricultural settlement of Bulhoek, where they took up residence in the vicinity of white farmers. Tensions rose. Defiant Israelites refused to obey orders to disperse. On May 23, 1921, the police mobilized. Warning shots were fired, but no one moved. The police opened fire, and an estimated 180 white-robed Israelites were killed. In the aftermath, Smuts was blamed for inflaming the situation by reneging on a promise to meet Mgijimi.

In 1922, in the newly mandated territory of South West Africa, a rebellion by a Nama clan, known as the Bondelswarts, was put down by South African aerial bombing, killing more than 100. Because this incident came under the terms of the League of Nations, it drew international attention and, once again, criticism of Smuts’s aggressive response to nonwhite unrest. Smuts, though, was unmoved; before Parliament, he declared, “It leaves me cold.”

Smuts’s policies and reputation at home did little to tarnish his standing as a global force for self-determination and human rights. In 1945, at the conference held in San Francisco to create the United Nations, it was Smuts who proposed adding the phrase “fundamental human rights” into the preamble to its charter.

Yet Smuts once again refused to engage with the African National Congress, whose leader, the American-educated medical doctor Alfred. B. Xuma, was pressing for the recognition of black citizenship rights in terms of the Atlantic Charter. When the two men met by chance at a press gathering in New York in November 1946, where Xuma was lobbying the United Nations to prevent Smuts from annexing South West Africa, Xuma is said to have remarked wryly: “I have had to fly 10,000 miles to meet my prime minister. He talks about us but won’t talk to us.” At the very first meeting of the General Assembly, in 1946, Smuts was condemned by the leader of the Indian delegation on account of South Africa’s discriminatory treatment of its Indian minority population.

How to explain the disjunction between Smuts’s global and domestic reputations? He had been effective as an international statesman and moral leader because he represented a small country that had fought for its freedom against British imperialism, thus exemplifying the new international spirit of self determination. The world only vaguely appreciated the greater injustice suffered by South African blacks — though that, too, was changing. The emerging postwar order, and the beginnings of the post-colonial era, were already apparent, as was the recognition that segregation in South Africa was morally unacceptable.

In 1948, Smuts was swept from power by the National Party, whose winning campaign slogan was “apartheid.” Smuts, though no enemy of segregation itself, found the idea of complete separation of the races extreme and unwise. The National Party, turning his international standing against him, attacked Smuts for being under the sway of liberalism and for prioritizing his personal international reputation over white national interests. He died in 1950, recently installed as chancellor of Cambridge University, just long enough to see apartheid imposed across his country.

Smuts was a complex man whose mix of visionary idealism, cool realpolitik and segregationist sympathies have led many to dismiss him as a hypocrite. Some have seen his philosophical exposition of holism and personhood as self-serving efforts to disguise political contradictions in the name of a higher human purpose. Yet the contradictions that Smuts navigated were not only personal; they were global. Smuts came of age into a world where talk of national self-determination and freedom was largely limited to whites. His long career came to an end when mass democracy was on the rise, when decolonization was on the march, and as political freedoms and rights began to be seen as indivisible and universal. Although he comprehended those shifts, he was unable to respond to them.

Saul Dubow, a professor of Commonwealth history at Cambridge University, is the author of “Apartheid: 1948-1994.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.