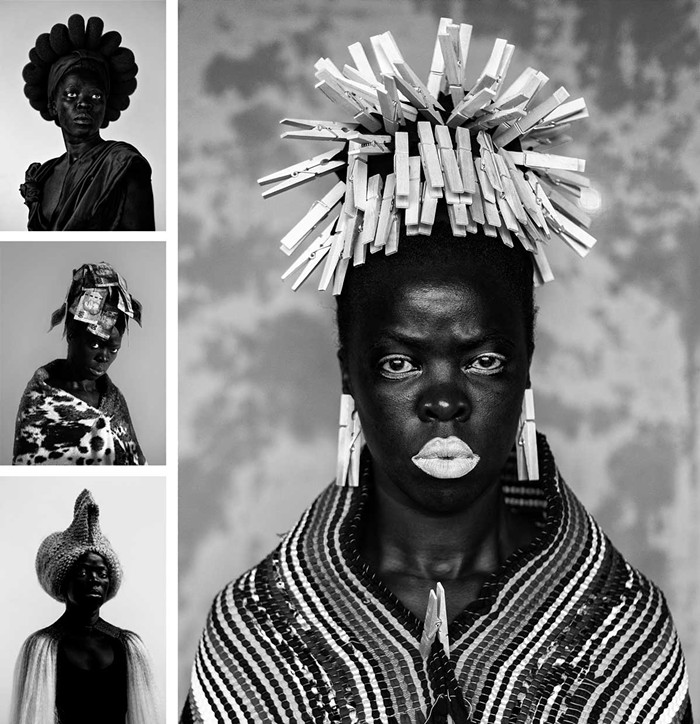

Each photograph contains only one subject: Muholi. The self-portraits were taken over a three-year period. All photos courtesy of Zanele Muholi and Seattle Art Museum

The exhibition is dimly lit. And it’s supposed to be—it’s part of what makes it great. When I walked through the press preview, someone requested that the lights in the galleries be turned up. Our guide politely declined. The South African photographer and “visual activist” Zanele Muholi, whose “self-portraits captured with a camera” compose the show, had come through just that morning to tweak the lighting the way they liked it, sure of how they’d like to be seen.

Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness consists of around 75 black-and-white self-portraits that spill out of Seattle Art Museum’s Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight Gallery and into the hallway and gallery that abut it. The walls are painted black, charcoal gray, and white, providing no bright contrast of any sort. Eight of Muholi’s portraits are blown up to the size of walls, almost physically involving the viewer in the composition; the others range in size, the smallest being the size of a large hand.

Each photograph contains only one subject: Muholi. The portraits were taken over a three-year period from 2014 to 2016 as Muholi traveled the world, giving guest lectures and participating in residencies in places like Oslo, Norway; Richmond, Virginia; and Mayotte, a French territory off the east coast of Africa.

“They are taken in various places wherever I wake up, so a sense of space is connected to my realities as I respond to many things I have encountered,” the artist told me. “This is my own way of undoing many things, including racism, but I use my own body as a subject of my own art.”

Muholi’s work is powerful because it recognizes the multiplicity of blackness and of self. It’s a reminder that to be black—as a condition, as a culture—is a complex state of being that’s often reduced to a single thing and, therefore, misread. Muholi’s personal ties to their queer and black community back in South Africa only deepen the ways in which their self-portraits can be read. Aesthetically, the work is both editorial and DIY, serious and playful.

The child of a Zulu mother and a Malawian father, Muholi was born in Umlazi, South Africa, in 1972. Muholi was a baby when their father died, and their mother worked as a maid to provide for the family. After completing an advanced photography course at Market Photo Workshop in Newtown, Johannesburg, Muholi had their first solo exhibition at Johannesburg Art Gallery in 2006.

In 2002, they cofounded and worked as a community-relations officer for the Forum for the Empowerment of Women, a black lesbian organization based in Gauteng, South Africa. They also reported and photographed for the blog Behind the Mask, which focused on gay and lesbian issues in the African continent.

This work set the stage for one of Muholi’s most discussed projects, their ongoing series Faces and Phases that began in 2006, for which Muholi photographs black lesbian, transgender, and intersex South Africans from their own community. The portraits came at a time when queer black South Africans were experiencing a wave of hate crimes and murders.

That series—which now includes more than 250 portraits—features queer couples and trans, lesbian, and genderqueer individuals presenting themselves to the camera, looking directly into the lens. It is, in part, a visual archive that does not play into any stereotypes or fears about this community, but rather respects and validates this community’s existence. These people whom Muholi photographs and works with are collaborators who accompany Muholi wherever they go.

Muholi’s work in Somnyama Ngonyama flows along a similar vein. “This [show] is on race, specifically responding to a number of events that are taking place in South Africa and beyond. There’s a lot of ongoing racism that is taking place and we hardly have the opportunity to respond as art practitioners or creatives to speak to such atrocities, violent racism, and displacement of our people,” the artist told me. “I’m not talking about myself only, but I’m talking about many other people whose voices are there but not heard.”

Most of the self-portraits in the exhibition at Seattle Art Museum feature Muholi looking directly at the camera, engaging the viewer. In the pictures, their skin appears uniformly darker than in real life, the whites of their eyes whiter, a result of them cranking up the contrast postproduction. They emphasized to me that there is no artificiality of any kind in their photographs, using only available light and spaces.

Eschewing high-quality materials, Muholi searched for discarded, mundane, cheap materials in each of the locations they traveled to, and then manipulated those findings to transform them into something greater than the sum of their parts. Often, these “un-African” materials were fashioned to resemble or recall something African, something that reminded Muholi of home. Rubber bicycle tires become a head wrap and dress; wooden clothespins become an elaborate headpiece; steel wool becomes a crown in tribute to their mother, Bester.

Whether using markers, wooden chopsticks, cheap dream catchers, power strips, vacuum tubes, blown up rubber gloves, scissors, chairs, hair buns from H&M, or actual money, Muholi embodies many different characters and selves. It’s more than just playing dress up, but rather an intended confusion for the viewer, each different character—lion, jester, king, queen, nurse, prisoner, lover—calling into question what we see when we see each other.

This embodiment challenges the presumed audience about their assumptions—here in Seattle, that audience is mostly white people—and about their own visual archive of black people. In the photograph Ntozakhe II, Parktown, 2016, Muholi is fashioned after the Statue of Liberty. Are black people in the United States truly free? If the Statue of Liberty were black, would our concepts of freedom and justice be different? In another wall-size photograph, Bhekisisa, Sakouli beach, Mayotte, 2016, Muholi’s body lies almost hidden among the rocks on a beach of Mayotte. To a viewer, what could that evoke? Refugees? As a critic, I’m keenly aware that I bring myself and my history to whatever I look at. Muholi is asking me to dissect and strip away that stuff.

When I mentioned Cindy Sherman—a white American artist known for her movie-like photographs in which she inhabits different characters—Muholi grinned. They get that comparison a lot. “Cindy cannot connect to our reality—not ever, not tomorrow,” the artist said, referring to the black community.

Each different character—lion, jester, queen, nurse, prisoner, lover—calls into question what we see when we see each other.

For comparison and context, they offered that black American visual artist Renee Cox is a better reference point. How we think about what an artist does requires an attentiveness, a willingness to look beyond our own ways of thinking, the connections we make, our own perception of the canon.

At the opening reception for the exhibition, I stood in the drink line behind an aloof-looking older white man who was making conversation with a younger black acquaintance about the show. He leaned in, familiarly, conspiratorially, referencing the photos: “They’re frightening, though, aren’t they?”

His acquaintance gave a humorless chuckle before grabbing a drink and slipping back into the crowd.

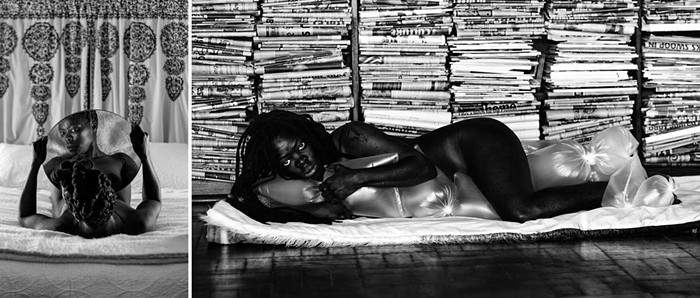

Frightening. My brain wrestled with the word as I watched the man sip his drink unbothered and wander back into the celebration. My thoughts drifted back to earlier in the day when a white woman asked Muholi if their portrait Julile I, Parktown, Johannesburg, 2016 was a reference to Édouard Manet’s Olympia. In the picture, Muholi is lying, naked, in front of tall stacks of newspapers while a length of plastic pads wraps around their leg.

Muholi was quick to correct the woman: No, no, this photo was taken days before an operation they were to have that would take tumors out of their uterus. This self-portrait was about the state of panic they were in surrounding whether or not they’d survive the surgery. Manet was not on their mind.

In no portrait does Muholi give a smile. The photos are not meant to appease in that sense. But that does not mean that there is a lack of emotion in the show. Rather, there’s an abundance of emotion.

“There are images that are super ugly,” the artist told me. “There are images that will make the next person feel like, ‘Wow!’ There are other images where you’re like, ‘Why do we have to look at this?’ It is through those images in which I want other people to find their own responses.”

That made me wonder about the responses I’d witnessed. Could it be that Muholi’s blackness was read as something to be feared, and their pain was read as beauty? The white woman referencing Manet misread the pain of Muholi’s photograph and saw beauty. The white man looked at Muholi’s willingness to present their body—their culture, their history, their sexuality, their many selves—and saw something frightening, perhaps his own fear. Maybe he saw that he didn’t know what he didn’t know.