Armed Conflicts, Asia-Pacific, Civil Society, COVID-19, Economy & Trade, Featured, Headlines, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, Sustainable Development Goals, TerraViva United Nations

Anti-government protest in Sri Lanka on April 13, 2022. Credit: Wikipedia

– Sri Lanka has been faced with an unprecedented political and economic crisis since the beginning of 2022.

The dominant narrative attributes the crisis to the confluence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ukraine conflict, China’s ‘debt trap diplomacy’ and – most importantly – the corruption and mismanagement of the ruling Rajapaksa family.

Western mainstream media celebrated the so-called aragalaya (struggle, in Sinhala) protest movement that led to the ouster of the Rajapaksas and upholds the IMF bail-out as the only solution to the dire economic situation.

The aragalaya protests emerged from genuine economic grievances, but failed to develop an analysis beyond the ‘Gota, Go Home’ demand for Gotabaya Rajapaksa to resign. Influenced by local and external interests with their own agendas, the protestors exhibited little-to-no awareness or critique of the global political economy and the financial system at the root of the country’s crisis.

In 2022, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reported that 60 percent of low-income countries and 30 percent of emerging market economies are ‘in or near debt distress.’ While the details differ from country to country, the historical patterns of subordination that have given rise to global crises are the same.

The Sri Lankan crisis is an illustrative example of convergent global debt, food, fuel and energy crises facing much of the world. It is corporate media bias and narrative control that deflects from this analysis.

The island’s severe debt and economic crisis must be seen in a broader global context as the culmination of several centuries of colonial and neo-colonial developments, and the disastrous and inevitably self-destructive capitalist paradigm of endless growth and profit. Debt is not “a straightforward number but a social relation embedded in unequal power relations, discourses and moralities…and…institutionalized power.”.

Colonialism and Neocolonialism

The development of export agriculture and the import of food and other essentials under British colonialism turned Sri Lanka into a dependent ‘peripheral’ unit of the global capitalist economy.

Adopting ideologies of modernization and development and theories of comparative advantage, the capitalist imperative integrated self-sustaining indigenous, peasant, and regional economies into the growing global economy, through the appropriation of land, natural resources, and labor for export production.

Monocultural agriculture, mining, and other export-based production disturbed traditional patterns of crop rotation and small-scale subsistence production that were more harmonious with the regional ecosystems and cycles of nature.

Plantation development contributed to deforestation, loss of biodiversity and animal habitats. While a small local elite prospered through their collaboration with colonialism, most people became poor, indebted, and dependent on the vagaries of the global market for their sustenance.

Although colonized countries including Sri Lanka gained political independence following World War II, unequal exchange continued under neo-colonialism. Terms of trade disadvantaged the ‘Third World’ with their labor, resources and exports grossly undervalued and imports overvalued.

The dynamic is better understood as poorer countries being over-exploited rather than under-developed. Rising populations combined with corruption and inefficiency of local governments gave rise to endemic foreign exchange shortages and economic crises in Sri Lanka and many other countries.

The debt relief and aid given by the IMF, the World Bank and bilateral institutions from the Global North have been mere band-aids to keep the ex-colonial countries tethered to the global financial and economic structures. Post-independent Sri Lanka went to the IMF 16 times before the current 2023 bail-out which seeks to further perpetuate the county’s cycle of debt dependence.

The transfer of financial and resource wealth from poor countries in the global South to the rich countries in the North is not a new phenomenon. It has been an enduring feature throughout centuries of both classical and neo-colonialism. Between 1980 and 2017, developing countries paid out over $4.2 trillion solely in interest payments, dwarfing the financial aid they received from the developed countries during that period.

Currently, international financial institutions – notably the IMF and the World Bank – remain outside political and legal control without even ‘elementary accountability’. As critics from the Global South point out, “The overwhelming power of financial institutions makes a mockery of any serious effort for democratization and addressing the deteriorating socioeconomic living conditions of the people in Sri Lanka and elsewhere in the Global South.”

Financialization and Debt

Corporate and financial deregulation which accompanied the rise of neoliberalism starting in the 1970s has given rise to financialization, and the increasing importance of finance capital. As more and more aspects of social and planetary life are commoditized and subjected to digitalization and financial speculation, the real value of nature and human activity are further lost.

As a 2022 United Nations Report points out; food prices are soaring today not due to a problem with supply and demand but due to price speculation in highly financialized commodity markets.

A handful of the largest asset management companies, notably BlackRock (currently worth USD $ 10 trillion) control very large shares in companies operating in practically all the major sectors of the global economy: banking, technology, media, defense, energy, pharmaceuticals, food, agribusiness including seeds, and agrochemicals.

Financial liberalization advanced when interest rates dropped in the richer countries after the global 2008 financial crisis. Developing countries were encouraged to borrow from private international capital markets through International Sovereign Bonds (ISBs) which come with high interest rates and short maturation periods.

Although details are not available to the public, BlackRock is reportedly the biggest ISB creditor of Sri Lanka. Most of Sri Lanka’s foreign debt is ISBs, with over 80% of Sri Lanka’s debt owed to western creditors, and not – as projected in the mainstream narrative – to China.

IMF debt financing requires countries to meet its familiar structural adjustment conditions: privatization of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), cutbacks of social safety nets and labor rights, increased export production, decreased import substitution and alignment of local economic policy with US and other Western interests.

These are the same aims as classical colonialism, they are just better hidden in the more complex modern system and language of global finance, diplomacy and aid.

A vast array of policies exacting these aims are well under way in Sri Lanka, including the sale of state-owned energy, telecommunications and transportation enterprises to foreign owners, with grave implications for Sri Lanka’s economic independence, sovereignty, national security and the wellbeing of her people and the environment.

The IMF approach does not address long-term needs for bioregionalism, sustainable development, local autonomy and welfare. A small vulnerable country such as Sri Lanka cannot change the trajectory of global capitalist development on its own.

Regional and global solidarity and social movements are necessary to challenge the deranged global financial and economic system that is at the root of the current crisis.

Global South Resistance

Since the 1970s, major collaborative projects have been initiated by developing countries and the UNCTAD to develop a multilateral legal framework for sovereign debt restructuring. Yet they are futile in the face of the powerful opposition of creditors and the protection given to them by wealthy countries and their multilateral institutions, and the UN has failed to uphold commitment and implement a debt restructuring mechanism.

Sri Lanka was a global leader in efforts to create a New International Economic Order, the Non-Aligned Movement and the Indian Ocean as a Zone of Peace in the 1960s and 70s. In the early years of their political independence, countries throughout Asia, Africa and Latin America sought to forge their own paths of economic and political development, independent of both capitalism and communism and the Cold War.

These included African socialist projects such as Tanzania’s Ujamma, import substitution programs in Latin America and left-wing nationalism and decolonization efforts in Sri Lanka and many other countries.

Almost without exception, these nationalist efforts failed, not only due to internal corruption and mismanagement but also due to persistent external pressure and intervention. Massive efforts have been taken by the Global North to stop the Global South from moving out of the established world order.

A case in point is the nationalization of oil companies owned by western countries in Sri Lanka in 1961 and the backlash against the left-nationalist Sri Lankan government which dared to take such a bold move.

The western response included the 1962 Hickenlooper Amendment passed in the U.S. Senate stopping foreign aid to Sri Lanka and to “any country expropriating American property without compensation.” As a result, Sri Lanka lost its credit worthiness, the domestic economic situation worsened, and the left-nationalist government lost the 1965 elections (with some covert US election support).

Observing those developments, political economist Richard Stuart Olsen wrote: “…the coerciveness of economic sanctions against a dependent, vulnerable country resides in the fact that an economic downturn can be induced and intensified from the outside, with the resulting development of politically explosive ‘relative deprivation’…”

These observations resonate with Sri Lanka’s current repetition of the same vicious cycle: an externally dependent export-import economy; worsening terms of trade; foreign exchange shortage; policy mismanagement; external political pressure; debt crisis; shortages of food, fuel and other essentials; mass suffering; and political turmoil.

Geopolitical Rivalry

Sri Lanka’s present economic crisis – the worst since the country’s political independence from the British – must be seen in the context of the accelerating neocolonial geopolitical conflict between China and the USA in the Indian Ocean. Many other countries across the world are also caught in the neocolonial superpower competition to control their natural resources and strategic locations.

There is much speculation as to whether the debt default on April 12, 2022 and political destabilization in Sri Lanka were ‘staged’ or intentionally precipitated to further the US’s ‘Pivot to Asia’ policy, the Indo-Pacific Strategy and the Quadrilateral Alliance (USA, India, Australia and Japan) in its competition to confront China’s $1 trillion Belt and Road Initiative and counter China’s presence in Sri Lanka.

It is widely recognized in Sri Lanka that ‘The policy of neutrality is the best defence Sri Lanka has to deter global powers from attempting to get control of Sri Lanka because of its strategic location.’ Although President Gotabaya Rajapaksa claimed to pursue a ‘neutral’ foreign policy, the Rajapaksas were seen as closer to China than the west. After Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa and President Gotabaya Rajapaksa were forced to resign, Ranil Wickramasinghe – a politician who was resoundingly rejected in the previous elections by the electorate but is a close ally of the west – was appointed as President in an undemocratic transition of power.

To what extent were Sri Lanka and her people victims of an externally manipulated ‘shock doctrine’ and a regime change operation, sold to the world as internal disintegration caused by local corruption and incapability?

While it is not possible to provide definitive answers to these issues, it is necessary to consider the available credible evidence and the geopolitics of debt and economic crises in Sri Lanka and the world at large.

Paradigm Shift

As the locus of global power shifts from the west and a multipolar world arises, new multilateral partnerships are emerging for development financing, such as the New Development Bank (NDB) – formerly referred to as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) Development Bank – as alternatives to the Bretton Woods and other western dominated institutions.

However, given controversial projects, such as China’s Port City and India’s Adani Company investments in Sri Lanka as well as their projects elsewhere, it is necessary to ask if the BRICS represent a genuine alternative to the prevailing political-economic model based on domination, profit and power?

Dominant political power in our era is about propaganda, control of narratives and exploiting ignorance and fear. In the face of worsening environmental and social collapse across the world, there is a practical need for a fundamental questioning of the values, assumptions and misrepresentations of the dominant neoliberal model and its manifestations in Sri Lanka and the world.

At the root of the crisis, we face is a disconnect between the exponential growth of the profit-driven economy and a lack of development in human consciousness, i.e., in morality, empathy, and wisdom.

Ultimately, dualism, domination and the unregulated market paradigm need to be questioned to find a balanced path of human development, based on interdependence, partnership and ecological consciousness. Such a path of development would uphold the ethical principles necessary for long-term survival: rational use of natural resources, appropriate use of technology, balanced consumption, equitable distribution of wealth, and livelihoods for all.

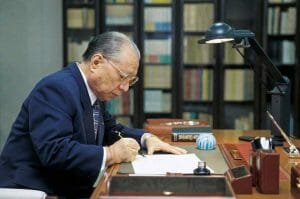

This article is derived from the author’s new book: Asoka Bandarage, CRISIS IN SRI LANKA AND THE WORLD: COLONIAL AND NEOLIBERAL ORIGINS: ECOLOGICAL AND COLLECTIVE ALTERNATIVES (Berlin: De Gruyter,2023) https://www.degruyter.com/document/isbn/9783111203454/html?lang=en]

IPS UN Bureau