Climate Change, Combating Desertification and Drought, Conferences, Economy & Trade, Environment, Food and Agriculture, Food Security and Nutrition, Food Sustainability, Global, Headlines, Health, Humanitarian Emergencies, Labour, TerraViva United Nations

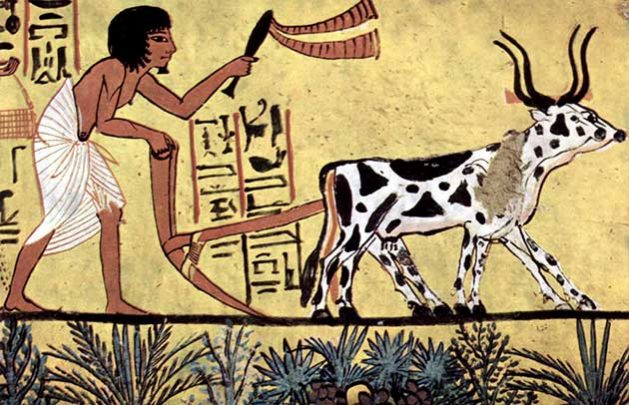

Oxen have been used to plough in agriculture for at least 3,000 years. They are still used today. Painting from the burial chamber of Sennudjem c, 1200 BC, Egypt. Credit: Trevor Page

– Why is the UN holding a Food Systems Summit? Two issues that need discussion at the international leadership level are: Long before the Covid crisis was upon us, the number of hungry people in the world was increasing. Why ? What is the cause of this disturbing trend? And, can a country really claim to be food secure, unless it produces or can buy enough food to feed its population and its people can access sufficient quantities to keep themselves fit and healthy? Disquietening questions as extreme weather begins to show the destructive power that climate change will have on the planet and its people.

A whole range of food system issues will be discussed at the summit, among them: production, processing, supply chain, consumption, nutrition, malnutrition, food aid and waste.

Food Production

Food, or the nutrients it contains, is fuel for the body. Agriculture and the production of food in an organized way is one of the earliest human endeavors. It started in the fertile crescent of the Middle East, some 10,000 BCE. While mechanization dominates the way food is produced today in the major food producing countries, animal traction is still important in many parts of the world.

Million dollar combines handle reaping, threshing, gathering and winnowing in a single operation on North American and European cereal fields today. GPS programmed, they are set to become driverless within a decade. Fruit and vegetables grown in vertical farms in cities using aquaponics are already springing up around the world. Aquaculture too can be moved to vertical farms, making fish much cheaper for urban dwellers. Vertical farms will greatly reduce labour costs and transportation requirements. Mechanization hugely reduces the number of people engaged in farming and consequently, the cost. Robotics and digital agriculture are already with us in some parts of the world. But where most people live in the world, traditional manual methods and animal traction are set to continue until the high investment needed for cutting-edge technology becomes doable.

Combines harvesting barley for the 2021 annual Canadian Food Grains Bank (CFGB) food drive, Alberta, Canada. The grain is auctioned and the proceeds matched 4:1 by the Canadian government and used by CFGB to promote agriculture in developing countries. Credit: Trevor Page

Wrestling with nature

Despite the advances in technology, drought can badly affect a crop. Cereal crops in western Canada and the United States have been seriously affected by drought this year. Climate change presents the greatest challenge yet to agriculture, and to the human species, generally.

Agriculture is the largest emitter of greenhouse gasses contributing to climate change. According to FAO, the rearing of livestock accounts for the highest proportion because of the methane produced from enteric fermentation as well as manure left on pastures. Also according to FAO, 44% of GHGs are emitted from Asia, 25% from the Americas, 15% from Africa, 12% from Europe and 4% from Oceania.

Is organic agriculture the answer to healthier food and also the way to go because it’s kinder to the planet? Studies have found that there are higher antioxidant levels in organically grown plant-based foods. There is also evidence that organic food has lower toxic, heavy metal levels and less pesticide residue, for instance organic eggs, meat and dairy products. Organic farms use less energy and have lower GHG emissions. They also reduce the pollution caused by the widespread use of nitrogen fertilizer on industrial farms, with the runoff causing the eutrophication of water bodies. Organic agriculture is based on nourishing the soil with composts, manure and regular rotations, keeping it covered with different crops throughout the year. That sequesters carbon, building healthier soil.

The problem is that organically grown food is more expensive that industrially produced food. On average, it retails around 25% more than food sold in supermarkets. Also, most organic farmers need to supplement their income from an additional occupation in order to make ends meet. So, despite the benefits to human health and to the planet, does organic farming have a future? The answer is a resounding “yes!”, both from producers and consumers. Although globally, only 1.5% of farmland is organic, in 16 countries 10% or more of all agricultural land is organic, and the proportions are growing. The countries with the largest organic share of their total farmland are Liechtenstein at 38.5 %, Samoa at 34.5% and Austria 24.7%, according to IFOAM Organics International. Today, organic food is more of a lifestyle choice, both by the producer and the consumer. But if its growth is an indicator of concern for our health and for that of the planet, and more and more people are willing and able to pay the extra cost involved, then organics can be seen as an indicator of wellbeing and a reduction of inequality, which is a major cause of conflict in the world today.

Healthy root formation on Mozart red potatoes on The Perry Farm in Taber, Canada. Regenerative agriculture is practiced on this farm. Credit: Trevor Page

Although humankind has grown up largely on a diet of just three cereals: wheat, corn and rice, potatoes are actually more nutritious. Furthermore, potatoes can be grown on marginal land and they require only one-third of the water needed to grow the world’s three main cereals. Five years ago, China moved to double its potato production and to add them to the diet of its growing population. Should Africa be following suit?

Conclusion

The Food Systems Summit kicks off in New York on September 23 during the UN General Assembly High-Level Week. World leaders will come together to find common ground and form alliances that accelerate our way to realizing the SDGs in this remaining decade of action before 2030 is upon us. Will we succeed in making Zero hunger a reality? If we are serious about this goal, the answer includes rethinking and redesigning our food systems to make them more sustainable.

Trevor Page, resident in Lethbridge, Canada, is a former Emergencies Director of the World Food Programme. He also served with the UN Food & Agriculture Organization, FAO, the UN refugee agency, UNHCR and what is now the UN Department of Political and Peace Building Affairs.