Armed Conflicts, Civil Society, Crime & Justice, Featured, Global, Global Governance, Headlines, Human Rights, Humanitarian Emergencies, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, TerraViva United Nations

The writer is a Researcher with the Peace Operations and Conflict Management Programme at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)

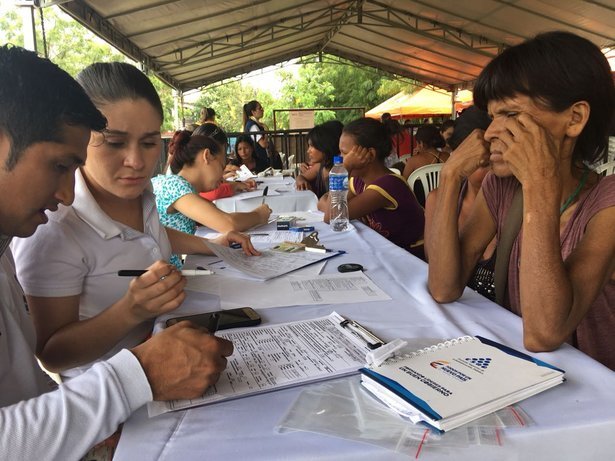

Female peacekeepers from South Africa on patrol in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. July 2021. Credit: MONUSCO/Michael Ali

– The first year of the Covid-19 pandemic saw wide-ranging impacts on multilateral peace operations.

The crisis simultaneously affected all operations, host nations, headquarters and contributing countries. It caused major disruption—from the political-strategic level where mandates are drawn up, down to the operational and tactical levels.

Operations were forced to adapt in order to preserve continuity as far as was possible. While some of the effects of the pandemic are clearly reflected in the data—most notably in mission mortality rates—others are not.

For example, SIPRI data on personnel deployments cannot always capture delays in troop rotations or whether mission personnel were evacuated or working remotely for part of the year.

However, there is some evidence that Covid considerations did affect deployments, as is noted below.

Operations close in Guinea-Bissau and Sudan

There were 62 multilateral peace operations active in 2020, the same number as in 2019. The largest share of these (21) were conducted by the UN. Regional organizations such as the African Union (AU) and the European Union (EU) and alliances (such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO) together conducted 36 operations. Ad hoc coalitions of states conducted 5 peace operations in 2020.

Two small operations in Guinea-Bissau closed in 2020. One was conducted by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS): the ECOWAS Mission in Guinea-Bissau (ECOMIB), the other by the UN: the UN Integrated Peacebuilding Office in Guinea-Bissau (UNIOGBIS).

One other operation that closed during the year was the AU–UN Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID), which was launched in 2007. UNAMID had deployed between 20 000 and 25 000 international personnel at its height in 2009–14, and it still deployed around 6500 in 2020.

A small political mission based in Khartoum, the UN Integrated Transition Assistance Mission in the Sudan (UNITAMS), opened on 1 January 2021.

UNAMID’s closure is a landmark in contemporary peacekeeping. It is the fourth major UN peacekeeping operation to close since 2017; the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) and the UN Operation in Côte d’Ivoire (UNOCI) both closed in 2017 and the UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL) in 2018.

Only seven operations comprising more than 5000 international personnel were still active at the start of 2021, and no operation deploying more than 1500 international personnel has been launched since 2014.

Three smaller operations open in CAR and Libya

The three operations that opened in 2020 were also in Africa. Two opened in the Central African Republic (CAR), in the wake of the 2019 Political Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation.

The AU Military Observers Mission to the CAR (MOUACA) was authorized in July 2020 to help monitor implementation of the agreement.

The EU Advisory Mission in the CAR (EUAM RCA), mandated to support security sector reform, had been established in December 2019 but was not launched until August 2020. Both operations have an authorized strength below 100 international personnel.

The AU Mission in Libya, the third new operation, was established by a decision of the AU Assembly in February 2020 to ‘upgrade’ the AU Liaison Office in Libya ‘to the level of mission’.

The Covid-19 pandemic seems to have complicated the deployment and build-up of these operations. In fact, while EUAM RCA was up and running at the end of 2020, albeit not at full capacity, there is little public information available on the status and activities of MOUACA or the AU Mission in Libya.

The latest edition of SIPRI’s Map of Multilateral Peace Operations shows all operations active as of 1 May 2021—including some that are outside the scope of SIPRI’s definition, such as the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) against Boko Haram, the Joint Force of the Group of Five for the Sahel (JF-G5S) and the EU Naval Force in the Mediterranean Sea (Operation Irini).

Personnel deployments fall

The number of international personnel deployed in multilateral peace operations globally fell by 7.7 per cent, from 137 781 in 2019 to 127 124 in 2020.

This was the largest year-on-year decrease since the drawdown of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan in 2012–14. Around 87 per cent were military personnel, roughly the same proportion as in 2019.

Almost two-thirds of the deployed personnel in 2020 were serving in UN peace operations (66 per cent on average over the year). Almost three-quarters (74 per cent at the end of the year) were deployed in sub-Saharan Africa (both UN and non-UN operations).

The number of personnel deployed in UN peace operations globally and in multilateral peace operations (UN and non-UN) in sub-Saharan Africa declined for the fifth year in a row.

Both had peaked in 2015–16 following a period of rapid growth driven by the establishment of major operations in CAR and Mali and the expansion of major operations in Somalia and South Sudan.

The number of personnel deployed in UN peace operations fell by 2.4 per cent between 2019 and 2020 (from 88 849 to 86 712), reaching its lowest level since 2007.

Meanwhile, the number of personnel deployed in multilateral peace operations in sub-Saharan Africa decreased by 3.4 per cent (from 97 519 on 31 December 2019 to 94 201 on 31 December 2020), reaching its lowest level since December 2012.

Women continued to be under-represented among multilateral peace operations personnel in 2020, as reported in a SIPRI publication prepared for the 20th anniversary of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security last year.

Afghanistan: The end of NATO deployments imminent

The development that contributed most to the net reduction of peace operations personnel deployments last year was the agreement reached on 29 February 2020 between the United States Government and the Taliban on the withdrawal of all US forces from Afghanistan within 14 months.

Due to the subsequent drawdown of most US troops, the NATO-led Resolute Support Mission (RSM) shrank from 16 551 to 9592 personnel over the course of 2020.

The RSM was launched on 1 January 2015 and was mandated to train, advise and assist the Afghan National Security and Defense Forces following the departure of ISAF, which had been active from 2001 to 2014.

The new operation was originally supposed to end on 31 December 2016, but it was not until April 2021 that NATO leaders formally announced their intention to terminate the RSM. The decision came shortly after US President Joe Biden had ordered the withdrawal of the remaining US troops from Afghanistan by 11 September 2021.

As a result of the withdrawal of most US troops from the RSM, the USA started 2020 as the second largest troop contributor to multilateral peace operations (after Ethiopia) and ended the year as the tenth largest.

Fewer blue helmets killed in action, more by illness than in previous years

In 2020, UN peace operations lost 78 uniformed personnel, 13 international civilian personnel and 32 local staff. The fatality rate for uniformed personnel was 0.9 per 1000.

This was noticeably higher than in 2018 and 2019, but around the average for the period 2011–20.

Despite this, the rate of hostile deaths (i.e. deaths caused by malicious acts) among uniformed personnel was at its lowest since 2011, at 0.15 per 1000.

This decline could conceivably be partly an effect of the pandemic, for example because peacekeepers were not able to patrol as much as usual or were otherwise less exposed to the risk of violence due to pandemic-related restrictions.

Meanwhile, the number of deaths due to illness among international and local personnel in UN peace operations in 2020 was almost double that in 2019 (83 compared to 42), with most of these deaths occurring between June and September 2020.

This difference is almost certainly linked in large part to the Covid-19 pandemic and its impacts, which contributed to a record number of deaths across the UN during the year.