Civil Society, Democracy, Featured, Headlines, Human Rights, Latin America & the Caribbean, Press Freedom, TerraViva United Nations

Luis Felipe López-Calva is UN Assistant Secretary-General and UNDP Regional Director for Latin America and the Caribbean

– Transparency is a critical element of making governance more effective. By making information available, it creates a foundation for greater accountability to citizens.

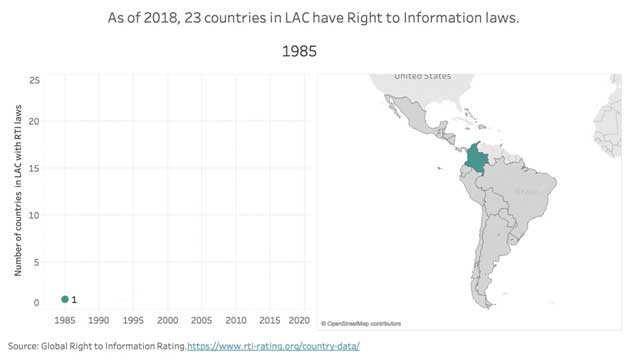

In recent decades, transparency has been on the rise across Latin America and the Caribbean. According to data from the Global Right to Information Rating, 23 countries in LAC have laws securing citizens’ right to information.

Colombia was the first country in the region to pass such a law in 1985, and Saint Kitts and Nevis was the most recent country to do so in 2018.

While transparency is a necessary condition for promoting accountability, it is not a sufficient condition. We can think about transparency as a first step.

While transparency makes information available, we also need publicity to make information accessible, and accountability mechanisms to make information actionable.

Information, per se, is nothing without publicity and accountability. If information does not reach the interested audiences, its effect is negligible. Similarly, even if information reaches the public, if it does not lead to consequences, its effect is not only negligible but potentially harmful.

For example, we have seen, unfortunately, many cases in our region where people can access detailed information about corruption cases, but nothing happens to those who are responsible. This leads to frustration and destroys trust.

Luis Felipe López-Calva

We can think about this progression from transparency to accountability as the “information value chain.” Recently, one way in which the information value chain has been broken in Latin America and the Caribbean is the intentional creation and spread of false information (what is known as “disinformation”).

In many cases these pseudo-facts are created for political purposes and target specific audiences, with the intention to induce certain outcomes (for example, by influencing voting behavior).

This system has been called the “fake news” industry—a term widely used by politicians in recent times. It’s important to note that false information can also be spread unintentionally (what is known as “misinformation”).

The rise of disinformation and misinformation has been facilitated by the rise of technology. Technology—particularly the rise of social media and messaging apps—has reduced the cost of disseminating information to massive audiences.

This has made the “publicity” industry more competitive and created a new social dynamic in which people often take access to information as equivalent to knowledge.

While knowledge is difficult to build and constantly update, information has become easy to get, and public debates are increasingly based on false—and often deliberately false—information.

Indeed, a recent study by scholars at MIT found that false news spreads much more rapidly than true news—and this effect is particularly salient for false political news (in comparison to false news about topics such as terrorism, natural disasters, science, urban legends, or financial information).

According the 2018 Reuters Institute Digital News Report, citizens in LAC countries are facing high exposure to false information, and are very concerned about what news is real and what news is fake on the internet.

In each of the four LAC countries included in the study (Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Argentina), over 35% of respondents stated that they were exposed to completely made-up news in the last week—reaching as high as 43% of the sample in Mexico.

Moreover, over 60% of respondents stated that they are very or extremely concerned about what is real and what is fake on the internet when it comes to news—reaching as high as 85% of the sample in Brazil.

This high level of concern is consistent with recent experiences with political disinformation in the region—for example, the use of automated bots to influence public opinion in Brazil, Argentina, and Venezuela.

This problem carries with it the concern for broader potential consequences such as deepening political polarization or the erosion of trust in the media. Indeed, over the past few decades years, the dissemination of false information by political parties and levels of political polarization are increasing in tandem in LAC.

This is a challenge not only in LAC, but in many regions around the world. This global preoccupation was reflected in the theme chosen for this year’s World Press Freedom Day—which focused on journalism and elections in times of disinformation.

Several of the countries in Latin America are holding presidential elections later this year: Argentina, Bolivia, Guatemala, and Uruguay. There is a concern in the region about how disinformation campaigns, coupled with microtargeting of political messages and sophisticated online advertising through social networks and online platforms, could affect the outcome of elections.

There is a lot we can do in this area to protect the information value chain and the quality of elections—such as “clean campaign” agreements between political parties, the creation of independent fact-checking services, greater enforcement by social media companies, and the promotion of information literacy among citizens.

In Latin America, these initiatives are still nascent, but they are growing. It is important to recognize, however, that combatting the challenge of disinformation campaigns will require the coordinated action of multiple stakeholders such as electoral courts, the media, civil society, academia and tech businesses (such as Facebook, Google, WhatsApp, and Twitter).

Without a strong coalition of actors, it will be difficult to successfully repair the information value chain and achieve accountability.