DOHA, Qatar, 18 February 2026-/African Media Agency(AMA)/- Thales, world leader in high technologies for Defence, Aerospace and Cybersecurity & Digital, plans to recruit more than 9,000 employees worldwide in 2026.

These hiring prospects follow the recruitment of 8,800 employees in 2025, exceeding the initially announced target of 8,000 new talent. Over the past 5 years, Thales has recruited at least 8,000 people per year to support the growth dynamics of its three business sectors.

In 2025, Thales received 1.4 million applications worldwide, exceeding its record of one million CVs received in 2024. The Universum ranking positioned Thales in first place amongst the most attractive employers for engineering school students in France (and second place in 2024).

Strengthening the diversity of teams and management committees remains a priority for the Group. In 2025, women accounted for 32% of all recruitments. 69% of the Group’s management committees are composed of at least 4 women and Thales aims to reach 75% in 2026.

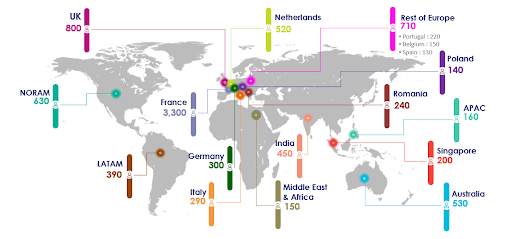

In 2026, Thales plans to recruit 150 people in the Middle East and Africa with 60 in the United Arab Emirates and 30 in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

In France, Thales will recruit 3,300 people, including 1,630 in the Ile-de-France, 290 in Brittany, 280 in Nouvelle Aquitaine, 270 in Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, 250 in Occitanie, 220 in Centre-Val de Loire, 180 in Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and 130 in Pays de la Loire.

In addition to the 9,000 external recruitments, and thanks to the variety of Thales’ three business sectors, roles and geographies, 3,500 employees will benefit from internal mobility. Additionally, the Group’s “Learning Company” approach, with more than 35 internal academies, will enable employees to develop their skills, thereby maintaining Thales’ expertise at the highest level worldwide.

Thales is committed to advancing the integration of people with disabilities, with an employment rate of over 7% in France in 2025.

Around 40% of new arrivals will be assigned to engineering (software and systems engineering, cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and data) and 25% to industry (technician, operator and engineer positions).

Thales reinforces commitment to inspire and support young talent in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM)

Thales is dedicated to fostering the careers of young people and places strong emphasis on welcoming apprentices and interns, particularly in France, where it will support 1,700 trainees and 1,600 apprentices from Bac+2 to Bac+5, as well as 1,000 third-year and 500 second-year students in 2026. For these young people, these opportunities serve as a stepping stone to future employment. In 2025, apprentices and interns accounted for 15% of Thales’ recruitment in France.

Through its “Vocation Makers” programme, Thales is actively engaging with young people ages 6 to 18 to spark their interest in science and technology. This is achieved through site visits and educational presentations in schools. In 2025, the Group met with 250,000 students worldwide, ranging from primary to high school levels.

In parallel, Thales has launched the STEM for All’s programme, a scholarship and mentorship initiative in partnership with the French Academy of Technologies. The programme is designed to support and inspire young students from disadvantaged backgrounds who aspire to pursue careers in STEM. In its inaugural year, 40 awards were given in France and Belgium, each including a €5,000 grant and one-year of mentorship from a Thales employee. In 2026, STEM for All will be expanded in 2026 to countries including the Czech Republic, Poland, Greece, Romania, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, Brazil and South Korea.

“We take great pride in seeing Thales’ appeal grow stronger year after year. The talented individuals who join us are driven by a desire to contribute to the development of sovereign, innovative, and sustainable solutions that the world needs more than ever. Together, we shaping the future by inspiring an increasing number of young people, especially young women, to pursue careers in science and technology.”

Patrice Caine, CEO of Thales

Candidates interested in the positions available at Thales can find out more and apply online at https://www.thalesgroup.com/fr/candidat and here for STEM for All.

Distributed by African Media Agency (AMA) on behalf of Thales

About Thales

Thales (Euronext Paris: HO) is a global leader in advanced technologies in advanced for the Defence, Aerospace and Cyber & Digital sectors. Its portfolio of innovative products and services addresses several major challenges: sovereignty, security, sustainability and inclusion.

The Group invests more than €4 billion per year in Research & Development in key areas, particularly for critical environments, such as Artificial Intelligence, cybersecurity, quantum and cloud technologies.

Thales has more than 83,000 employees in 68 countries. In 2024, the Group generated sales of €20.6 billion.

The post Thales to recruit more than 9,000 new employees in 2026 appeared first on African Media Agency.