Africa, Civil Society, Gender, Global Governance, Headlines, Human Rights, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, TerraViva United Nations

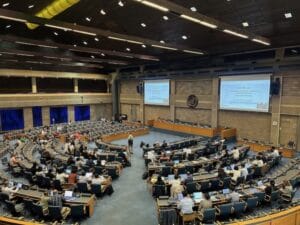

Credit: Equality Now

– Thandi*, a 14-year-old girl from Malawi, is both a child and a mother. After she and her siblings were orphaned, they were left in the care of their grandmother, who struggled to provide for them.

Thandi recalls with sorrow how two years ago, her grandmother ‘sold’ her to a much older man for a bride price of 15,000 Malawian Kwacha (approximately USD $8.65). This meager sum was only enough to buy a week’s worth of food for the family.

Forced to drop out of school to become a wife, Thandi’s dreams of education were abruptly curtailed when she left education in Standard 7 (Grade 6). She explains, “Watching my friends continue with their schooling while I grappled with the challenges of marriage has left lasting scars.”

Over 6,000 kilometers away in Nigeria’s north-western Niger State, at the end of May 2024, the local government orchestrated marriages for 100 young women. Most were orphans who lost parents in the frequent bandit attacks that plague the region. Local officials claim that all the brides were aged over 18, but there are serious concerns that many were minors.

Child marriage remains widespread across Africa

A new report by Equality Now, Gender Inequality in Family Laws in Africa: An Overview of Key Trends in Select Countries, reveals pervasive discrimination in family laws across Africa, where child marriage remains widespread.

The continent is home to 127 million child brides. Although global rates of child marriage have declined from 23% to 19%, current trends suggest that by 2050, nearly half of the world’s child brides will be African.

The causes of child marriage are multifaceted. Challenges such as climate crisis, conflict, and socio-economic instability disproportionately affect women and girls, putting them at greater risk of human rights violations.

Rather than addressing systemic issues like poverty, sexual violence, and poor access to social support and reproductive healthcare, communities often resort to marrying girls off.

Governments are failing to protect girls

As in Thandi’s case, child marriage is commonly treated as a socio-economic band-aid. In her home country of Malawi, the practice has been completely illegal since 2017, when the government took the commendable step of raising the age of marriage to 18 for both boys and girls without exception.

However, child marriage remains widespread amongst a population that has over 70% living below the international poverty line, with 2020 data showing that 38% were married before the age of 18,

The situation is similar in other African countries. Niger is reported to have the world’s highest rate of child marriage among girls, with 76% married before 18. While in Mauritania, World Bank research cited that girls from the poorest households are almost twice as likely to marry compared to those living in the richest households.

Child marriage reinforces gender inequality, with girls viewed primarily as wives and mothers. What is especially concerning is how these harmful societal norms are sometimes state-backed by governments less willing to uphold girls’ rights.

In Mali, a watershed judgment by the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights in 2018 found Mali’s Personal and Family Code, which allows girls to marry at 15 or 16 while setting the same for boys at 18, violated Mali’s international and regional human rights obligations.

The African Court directed Mali to revise its Family Code to set the minimum age of marriage for both girls and boys at 18. Mali’s government has not yet implemented the judgment, rendering girls vulnerable to becoming child brides.

In Tanzania, a landmark judgment in 2016 mandated the government to set the minimum age of marriage for both boys and girls at 18, but Tanzania has yet to amend the Law of Marriage Act. This failure to enforce the judgment is leaving girls unprotected and is compounded by challenges that pregnant girls and adolescent mothers face in accessing education.

Tanzania’s long-term policy of expelling pregnant students from school was ruled by the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACERWC) in 2022 to be a violation of girls’ human rights.

While the government has subsequently officially withdrawn this policy, the provisions in the Education Act that authorise exclusion from school of girls who are married, pregnant, or mothers remains unchanged, and there are serious concerns about the impact of Tanzania’s failure to fully implement ACERWC’s decision.

Girls across Africa who become pregnant may face the trauma of being forced to marry as a way to uphold family “honour” and avoid the social stigma associated with pregnancy outside of wedlock.

A cycle of abuse is perpetuated with young wives often denied access to education and economic opportunities, leaving them dependent on their husbands and in-laws. This makes them more susceptible to domestic violence and limits their ability to seek help or escape abuse.

African States have legal obligations to protect girls from early marriage

Child marriage is a gross violation of human rights and is prohibited by Article 16(2) of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), Article 6 of the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol), and Article 21 (2) of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (the African Children’s Charter).

The Constitutive Act, which established the African Union, recognizes the promotion of gender equality as a fundamental principle of the Union. Guidance on how Member States can end child marriage is provided by instruments such as the Joint General Comment of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) and the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACERWC) on Ending Child Marriage.

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) Model Law on Eradicating Child Marriage and Protecting Children Already in Marriage is another great source for states to consider.

Government progress has been slow and inconsistent

Equality Now’s family laws report notes laudable progress, with comprehensive bans on marriage under 18 years introduced in various countries, including Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, and The Gambia.

However, progress overall has been protracted, inconsistent, and impeded by setbacks, insufficient political will, and weak implementation. Challenges are compounded by the plural legal systems in many African countries, where religious and customary legal provisions often contradict regional and international human rights standards.

In countries such as Cameroon, Nigeria, Senegal, South Sudan, Sudan, and Tanzania, discriminatory age limit provisions permit girls to be married younger than boys, while in nations including Angola, Algeria, and Tunisia, exceptions on civil or customary grounds remain.

Education is a remedy for child marriage

Urgent action is needed by 2030 to ensure all girls complete a full cycle of basic education. African leaders must work fast to develop and accelerate the implementation of progressive education policies that align and integrate with laws and policies addressing child marriage.

Strengthening legal frameworks to ensure the minimum age of marriage is set at 18 without exceptions is essential. Prosecution and punishment of perpetrators should be accompanied by behavior change campaigns that shift social norms and raise awareness about the harms of early on girls, their children, and the wider society.

Underpinning this all should be the application of a multi-sectoral approach entailing coordinated efforts across multiple sectors, including the state and civil society. Government policy and funding must prioritize women’s rights and define the responsibilities of different government arms, including health, finance, justice, social welfare, youth, and education agencies.

Providing scholarships and financial incentives, such as conditional cash transfers, can help keep girls in school and diminish the economic incentives for early marriage. Rwanda is a good example, having achieved significant increases in girls’ school enrolment and a corresponding decrease in child marriage.

The country has made education free and compulsory through secondary school, and the state is investing heavily in teacher training and school infrastructure.

Another noteworthy case is Ethiopia’s investment in the Berhane Hewan programme, which combines education with community awareness. Girls who participated were 90% less likely to be married before the age of 15 compared to those not in the programme.

Enhancing the capacity to collect, analyse, and use sex-disaggregated data for policymaking is also crucial for informed decisions. This data can highlight disparities and guide targeted interventions.

Moreover, implementing education programs that include comprehensive sex education is vital. Such programs empower girls with knowledge about reproductive health and their rights, thereby reducing rates of child marriage and early pregnancies.

In Mozambique, the Gender Strategy for the Education Sector aims to create equal rights and opportunities for girls in the education sector. While a strategy like this is geared towards equality in education, if data collection around child marriages is incorporated it can produce results on strategy’s impact on child marriage.

Governments must tackle the root causes of child marriage

To genuinely protect and empower young women, governments must address the underlying causes of girls’ vulnerabilities. This includes tackling drivers such as conflict and climate crisis, improving social protection systems, introducing legal reforms to prohibit child marriage without exception, and ensuring the effective implementation of laws.

Efforts must also be made to challenge and change harmful cultural and religious practices that undermine the rights of women and girls.

Critically, African Union Member States must universally ratify and implement the Maputo Protocol and the African Children’s Charter. To adequately equip girls to thrive in the 21st century, they must also discharge the education and gender equality obligations they have committed to under Agenda 2063 and Africa’s Agenda for Children 2040.

*Thandi is not her real name.

Deborah Nyokabi is Gender Policy Expert, Equality Now.

IPS UN Bureau