Climate Change, Crime & Justice, Economy & Trade, Food & Agriculture, Gender, Global, Headlines, Health, Human Rights, Inequity, Poverty & SDGs

Systemic racism in agriculture is painfully obvious. Why has it taken a new Civil Rights movement to clearly expose the sordid roots and present-day inequalities in food and farming?

Credit: Heifer International

– There has been far less social progress in the United States in the last 155 years than many people would like to believe. In 2020, racism still seeps its way into every aspect of life; from unconscious bias and micro-aggressions in everyday interactions to domestic and international policy and enforcement.

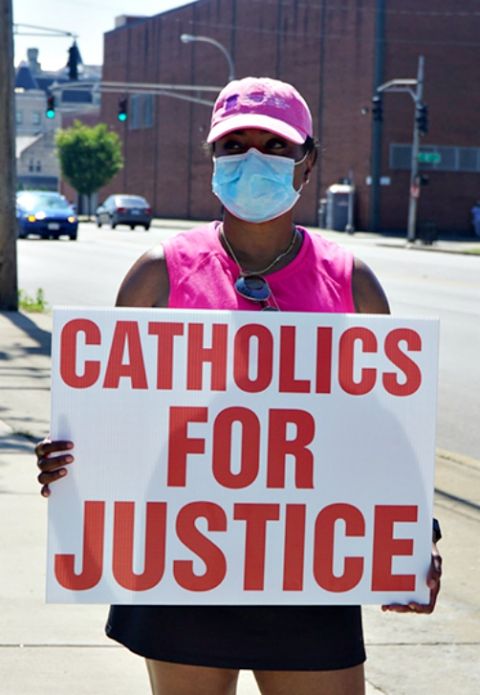

As an organization with 76 years of history supporting smallholder producers, we have a responsibility to use our experience to name and break the barriers that have plagued Black, Indigenous and People of Color farmers. Fighting injustice in all its forms – hunger, malnutrition, poverty, income inequality, climate change and gender inequity – has long been a tenet of our work.

A farmer who participated in the Heifer International and Prentiss Institute 30-year partnership in Mississippi. Credit: Heifer International

We have worked to break down barriers that prevent the inclusion and success of marginalized groups in agriculture. Heifer International has assisted with land rights, helped farmers organize, provided technical assistance to increase their production and productivity, and improved access to capital and to markets. But good intentions do not equal positive impact. It is not enough to mean well. We have to do well.

Our mission cannot be fulfilled without recognizing how deeply agriculture is rooted in racism. It’s imperative to address how synonymous the origins of our food system are with the battle currently being fought – how the success of global agriculture has been sown with the blood and sweat of people of color.

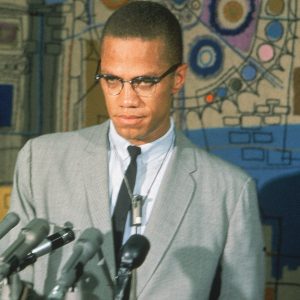

In the United States, modern agriculture was built on the backs of enslaved people who were used as property and valued only as production units. They produced cotton, tobacco, sugar, indigo, rice, sweet potato, peanuts, watermelon and okra. This unrelenting free labor, coupled with simultaneous extraction of farming knowledge, directly led to America’s economic domination of the 18th century and pervasive industrialized agricultural ascendancy that remains today — facilitating an empire of production, processing and trade. When slavery finally became illegal, the tradition of Black exploitation for food-flow gain continued in the form of tenant farming, sharecropping and land grabbing.

In the 1930s, as minimum wage and other legislation was enacted to protect labor rights, the agricultural industry remained exempt and farmworkers (at the time, predominately African American) were excluded; this loophole was not modified until the 1980s. Simply put, our country’s designation as the ‘crop basket of the world’ would not have been possible without the unwilling sacrifice of Africans and African Americans.

But today, the Black community is disproportionately impacted by food insecurity, malnutrition, diet-related disease, lack of land ownership and largely exclusion from agriculture as a whole.

Farmer works in her peanut field in Zambia. Credit: Heifer International

The U.S.’s agricultural foundation follows a tradition of forced labor spanning huge expanses of time and place. Most of our favorite grocery items are a product of colonialism, widely available thanks to the almost standardized practice of one powerful predominantly white nation dropping anchor onto a foreign land, conquering and brutally subjugating its indigenous people, ravaging the soil with the compulsory workforce of human ‘property,’ and sending resulting agricultural goods back to its own and other wealthy countries at an enormous profit.

Farmer works in her familys sweet potato field in Malawi. Credit: Heifer International

The Dutch East Indies brought Arabica and sugar, British India produced tea and spices, German East Africa ushered in sesame and Robusta, French West Africa brought chocolate and peanuts and the Belgian Congo palm oil and sugar. When slavery was no longer condoned, oppressive conditions on stolen land remained. While each wave of colonialism has its own nuanced narrative, they all propagated from the same seed – racism.

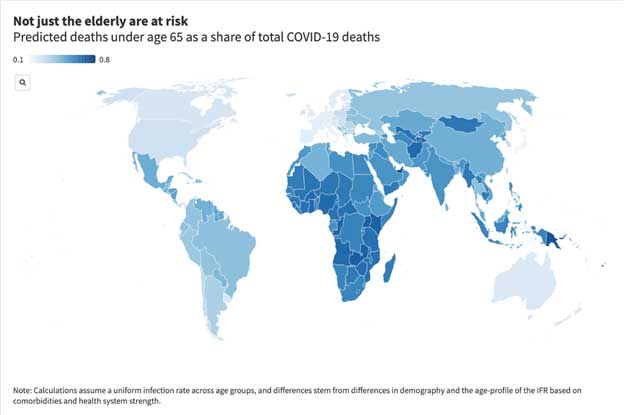

This subjugation continues to play out, under new names but similar practices, all over the world. In many countries, racial, indigenous, ethnic or caste groups are deemed ‘less than’ – less worthy of basic safety and human rights, of fair pay and equal opportunity and of dignity. Considering 70% of the world’s hungry are or used as food producers, it’s a statistical certainty that what is on our plates stems from one of these groups.

Poverty is not an accident. When entire groups of people experience similar forms of socio-economic marginalization, that is by design. It is intergenerational. It is systemic, born of racially and ethnically driven oppression. It is intolerable.

Farmer and farm worker Sevia Matinanga (right) harvest sugar cane in Zambia. Credit: Heifer International

We cannot change the past, but we can actively acknowledge it. We must begin the more critical work of changing the course of the future, which means actively supporting communities of color in our local and global food system. There’s much to be done. Governments must enact policies to ensure full, inclusive and healthy participation in agricultural livelihoods and access. Organizations like Heifer International need even deeper commitment to social, economic and environmental justice on every level of our work, saying “no” to complicit systems and “absolutely” to accelerating the visions marginalized smallholder farmers have for their futures. Consumers can seek out black-owned agri-businesses and take a stand against corporations that source ingredients for unethical prices and in many cases, via actual forced and/or child labor. The world is ripe for real change, and we are ready for it. Source