Civil Society, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Featured, Gender, Global, Global Governance, Headlines, Human Rights, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, TerraViva United Nations

Princess Sarah Zeid is a member of UNHCR’s Advisory Group on Gender, Forced Displacement, and Protection, a Special Advisor to the World Food Programme on Maternal and Child Health and Nutrition, and Chair of the Newborn Health in Humanitarian Settings Initiative.

– On the eve of the Women Deliver conference in Vancouver June 3-6, Princess Sarah Zeid of Jordan interviewed Dr. Olfat Mahmoud, a Palestinian refugee and women’s rights advocate.

Princess Sarah spoke with Dr. Olfat about what the humanitarian system would look like if organizations like hers could help shape it, and the messages she hopes to bring to Women Deliver.

Excerpts from the interview:

Princess Sarah: Tell me a little about yourself. What drew you to your work and why does it matter?

Dr. Olfat: I was born a Palestinian refugee, so witnessed injustice all my life. Yet what defines me is not that I grew up in a refugee camp in Lebanon, or that I spent most of my life in a war zone, but that I am a nurse and advocate in my community.

Even amid crisis, my parents were open-minded and encouraged me to be independent, so that is exactly what I set out to do. I studied and practiced nursing during the Lebanese civil war, and through that work witnessed the overlooked hardships faced by refugee women and children.

As a medical practitioner, I saw how essential services for girls and women of all ages – such as psychosocial support and sexual and reproductive health care– were chronically overlooked. And as an advocate in my community, I found that supporting women empowered me as well.

I established the Palestinian Women’s Humanitarian Organization (PWHO) to fill these gaps and fulfill the needs of refugee girls and women so they can lead better futures. Not a single international organization stepped up to do this important work – so I knew that change had to come from those of us within the community.

Princess Sarah: What are the main challenges girls and women face in your community? What makes women-focused civil society organizations (CSOs) like yours most well-equipped to respond to these challenges?

Dr. Olfat: For girls and women, life in refugee settings require superhuman strength. We are particularly vulnerable when it comes to access to essential health services, information, and education, and disproportionately suffer from gender-based violence.

Women-focused civil society organizations are most well-equipped to respond to these challenges because women are the best experts on our lives. Our lived experiences make us better advocates for ourselves and for others in similar situations.

For example, the PWHO women’s centers – staffed by refugee women themselves– have gained unparalleled trust from the community, and become a second home for many.

With that trust, we can more easily identify what women want and need – like access to non-discriminatory health services, psychosocial support, rights-based education, and leadership skills – and design programs that are tailored for them. We can also negotiate with local leaders to push for a more supportive environment for women’s rights – a key ingredient to driving lasting change in conservative contexts.

UNHCR Patron, HRH Sarah Zeid of Jordan, meets with a women’s group at Doro refugee camp in South Sudan. Credit: UNHCR/Jan Møller Hansen

Princess Sarah: What could the international community – including donors, decision-makers, and practitioners – do more or less of to maximize sustainable positive impact for the populations you serve?

Dr. Olfat: The international community wields a lot of power – especially the power of money and the power of influence. To drive real change in my community, international actors must use those powers more efficiently.

First, there is a critical need to fill funding gaps for programs that are specifically designed for refugee girls and women. With more girls and women displaced today than ever before in global history, their needs are rising – yet funding for them is decreasing.

We need smarter investments in programs that enable refugee girls and women to lead better futures, including through education and quality vocational and life skills training, as well as access to sexual and reproductive health care.

Yet money alone is not enough. The international community must also use their influence to challenge national and regional political barriers that hold us back.

This includes respecting and upholding international agreements, including UN resolutions, which support and protect refugees. It also means addressing legal restrictions that keep refugee women from working, obtaining formal education, and exercising other basic human rights in their host countries.

Princess Sarah: Currently only 3% of humanitarian aid goes to local and national organizations – and even less to those focused on girls and women. What types of concrete investments does your organization need to extend your impact and plan for the future?

Dr. Olfat: Right now, the needs we see are greater than the resources we have. To meet those needs, we don’t just need more funding – but more of the right kinds of funding.

Too often, grants and funding opportunities for women-focused CSOs are designed without consulting us on the types of investments we know girls and women in our communities need the most.

Other times, we aren’t able to access grants because of unrealistic reporting requirements that are either unsuitable or unmanageable for a small grassroots organization like ours.

For example, many grants for vocational programs in Lebanon require organizations to report success by the number of jobs their beneficiaries gain as a result – which isn’t possible in a context where refugees aren’t legally allowed to work. To support women-focused CSOs and the communities they serve, we must be more meaningfully engaged in setting investment agendas at the start.

We also need access to more flexible and sustainable funding opportunities, including core funding. It’s impossible to plan for the future when we rely on six- to twelve- month grants. We’re committed to supporting refugee girls and women in our community for as long as we’re needed – but require the right resources to fulfill that goal.

Princess Sarah: You have also been advocating for the international community to more meaningfully engage women-focused CSOs in humanitarian decision-making. In your view, what concrete steps can the international community take to put more power and influence in the hands of women-focused CSOs like yours, and why should this be an urgent priority?

Dr. Olfat: Women-focused CSOs must be heard in humanitarian policy meetings to ensure decisions reflect realities on the ground. This requires inviting us to important discussions held in New York and Geneva, but it also means making sure we can get there through travel and logistics support. And when we are there, it means carving out spaces for us to safely and honestly share the solutions we need with the assurance that we will be heard.

The alternative – excluding refugee women from decisions that affect their work and lives – isn’t acceptable and isn’t working. When we are engaged, we make humanitarian policy and practice stronger and more effective.

Princess Sarah: What do you hope to achieve at the Women Deliver Conference in Vancouver, Canada? What advocacy asks do you hope to bring forward at this meeting?

I hope to raise awareness to the needs of Palestinian refugee girls and women in Lebanon, to ensure that they are not forgotten. And I want to highlight solutions women-focused CSOs like PWHO need – money, influence, and power – to push for the change I’ve wanted to see all my life.

At the same time, I hope to learn from other advocates around the world, and build networks so we can collectively push for a humanitarian system that puts girls and women at the center. Solidarity is our strength and our power – and we need to be stronger together to achieve a better world for all of us.

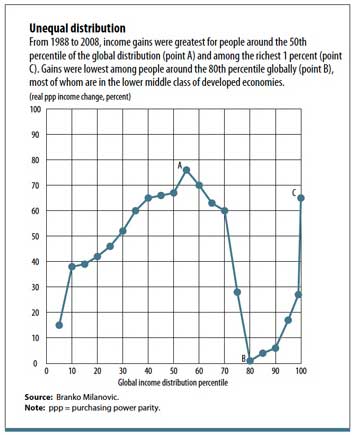

Meanwhile, the lower middle classes in advanced economies saw their earnings stagnate.

Meanwhile, the lower middle classes in advanced economies saw their earnings stagnate.

May 23, 2019

May 23, 2019

The aim of this Assembly was to invite the international community to take a joint stand against racism, racial discrimination and intolerance and to address the fundamental structural root causes of these scourges through a robust and universal implementation of the DDPA.

The aim of this Assembly was to invite the international community to take a joint stand against racism, racial discrimination and intolerance and to address the fundamental structural root causes of these scourges through a robust and universal implementation of the DDPA.