Armed Conflicts, Civil Society, Crime & Justice, Global, Headlines, Human Rights, Migration & Refugees, Natural Resources, Peace, Press Freedom, TerraViva United Nations

Michelle Bachelet, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. Credit: Jean-Marc Ferré/UN Photo.

– On 22 July 2019, Kenneth Roth published an article in Publico, Lisbon, entitled: “UN Chief Guterres has disappointed on Human Rights”.

This essay lampooning Antonio Guterres is not a voice “against the tide” but very much mainstream – and demonstrably skewed. Major NGOs headquartered in rich advanced countries and enjoying generous funding from the Establishment may not always think “out of the box” and are as likely, as are the interest groups which support them, to politicize human rights and therefore to disappoint rights holders in smaller or weaker countries.

While they do contribute to exposing situations of human rights violations worldwide , they are not exempt from biases which reflect the structure of their central governing bodies or the cultural environment within which they operate. They cannot arrogate to themselves the sole legitimacy to speak in the name of the civil society of many countries , and when they claim to do so, they may disappoint rightsholders, particularly in the developing countries, whose priorities are frequently different from theirs.

Sober analysis and stocktaking are necessary to determine whether and to what extent the priorities and agendas of NGOs’s like HRW are set by the overall interests of the established power-structures and multiple elites in many countries. Kenneth Roth’s article expressing disappointment at the human rights performance of Secretary General Antonio Guterres fails to identify the root causes of human rights violations.

His admonitions have little or no preventative value, and do not formulate constructive recommendations such as, for instance, the provision of advisory services and technical assistance to many countries that need it and have asked for it.

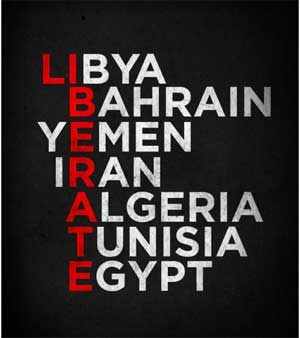

HRW’s “naming and shaming” strategy has been inconclusive at best because “naming and shaming” depends on the authority of the “namer” and the impartiality of the methodology. Kenneth Roth’s bludgeoning of the UN Secretary General in this regard is yet another expression of grandstanding and even of a measure of arrogance. HRW’s criticism of China, Russia, Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, would be more persuasive if the organisation addressed with the same intensity the egregious violations of human rights in many other countries.

For instance, Mr. Roth does not mention the denial of the right of self-determination to millions of people, the retrogression in the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights (prohibited by the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights), the looting of natural resources and degradation of the environment by transnational corporations and their neocolonial schemes, the impunity enjoyed by politicians who engage in aggressive wars and by paramilitaries and private security companies, the devastating human rights impact of blockades by source countries and economic sanctions on the populations of Gaza, Syria, Iran and Venezuela, which have caused and continue to cause tens of thousands of deaths.

The politicization or as we now witness with concern, the“weaponization” of human rights is taking the world on a slippery slope. When the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)was adopted in 1948, Eleanor Roosevelt, Charles Malik, René Cassin and others spoke of human dignity and the inalienable rights of human beings, but article 29 of UDHR also reminded us that “everyone has duties to the community”.

Indeed, what is most necessary is global education in human rights, including the human right to peace, education in empathy and solidarity with others – compassion, not predatory competition in “the human rights industry” on a “holier than thou” ticket.

Meanwhile, Secretary-General Antonio Guterres should not be expected to act as a Human Rights NGO. This high office is not that of an unaccountable activist. It is neither that of a general that can blast any state at will nor is it a secretary that has to be subservient to the prevailing powers that be.

That high official must recognize the reality of the power balance that he cannot fundamentally alter but must strive with obduracy and at times courage to stretch the international community towards more compliance with the purposes and principles of the United Nations. Most importantly this means the promotion of peace through conflict-prevention, good offices, impartial mediation, disarmament and yes, human rights. When all diplomacy fails and only then may “naming and shaming” become an option. But it is a default option and a sign of diplomatic failure.

In the experience of both of us as Special Rapporteurs of the Human Rights Council, we have delivered on our mandates, not by openly challenging the authority of states or claiming to teach them lessons in human rights but by giving quiet diplomacy a chance .

This is how one of us together with another Independent Expert facilitated a lifting of the sanctions on Sudan and this is how we are again currently engaging with protagonists of other conflicts. We have succeeded in confidence-building and contributed to the release of detainees. Persevering and discrete advocacy bears fruit.

We want a SG that puts values above politics in human rights matters and this is, in our opinion, what Guterres is doing. We have a Secretary General that can speak for truth and can at least listen to the narratives of the smaller and weaker states who have no access to the world media and whose action is distorted by biased reporting.

Of course the murder of Khashoggi is a tragedy because beyond the tragic loss of a human life, it is the freedom of expression that is targeted. But Kenneth Roth does not mention the thousands of migrants whose lives end in the liquid graves of the oceans because saving them at sea is becoming a criminal offence in some « enlightened » nations.

Are there different values attached to life according to the « exploitability » of its loss for political aims? We do not think that the Secretary General should go down along this road, even if this may cause disappointment in some quarters.

We would be really concerned if the Secretary general were to follow the path of selective indignation advocated implicitly by Mr Roth, because he would lose the moral leadership that we all, people of good will, can identify with across the world. THAT would be a major disappointment.

We welcome in Antonio Guterres a Secretary General who does not hesitate to call a spade a spade, a SG who promotes peace and does not stoke conflict, who challenges unilateral economic sanctions, who supports the Right to Development1 and places the Secretariat of the United Nations in its service. We welcome a SG who, together with the new UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, are engaging all of humanity in the noble task – day by day – of implementing civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights in larger freedom – and in good faith.

Idriss Jazairy Special Rapporteur, UN Human Rights Council

Alfred de Zayas Former Independent Expert, UN Human Rights Council

The truth was lost in this fierce political conflict and the Arab viewer had to cross-check the presented facts with other international reporting. This implicit bias and lack of balance polarized Arab public opinion and pushed news consumers to social media in search of trusted factual information, crushing the credibility in traditional media.

The truth was lost in this fierce political conflict and the Arab viewer had to cross-check the presented facts with other international reporting. This implicit bias and lack of balance polarized Arab public opinion and pushed news consumers to social media in search of trusted factual information, crushing the credibility in traditional media.