Active Citizens, Civil Society, Conferences, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Featured, Global, Global Governance, Headlines, Human Rights, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, Peace, Population, Regional Categories, TerraViva United Nations

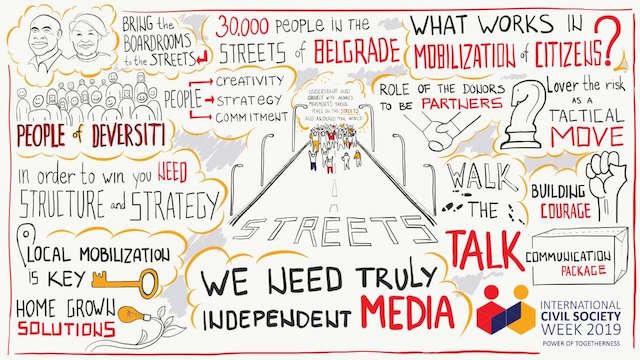

This article is part of a series on the current state of civil society organisations (CSOs), which was the focus of International Civil Society Week (ICSW), sponsored by CIVICUS, and which took place in Belgrade, April 8-12.

More than 200 civil society leaders and human rights activists from some 100 countries took to the streets of Belgrade, Serbia in solidarity with those whose basic freedoms are at risk. They participated in the International Civil Society Week (ICSW), sponsored by CIVICUS, which took place in Belgrade, April 8-12. Courtesy: CIVICUS

– Counterterrorism measures are not only affecting extremist groups, but are also impacting a crucial sector for peace and security in the world: civil society.

Civil society has long played a crucial role in society, providing life-saving assistance and upholding human rights for all.

However, counterterrorism measures, which are meant to protect civilians, are directly, and often intentionally, undermining such critical work.

“Civil society is under increased assault in the name of countering terrorism,” Human Rights Watch’s senior counterterrorism researcher Letta Tayler told IPS, pointing to a number of United Nations Security Council resolutions as among the culprits.

“Nearly two decades after the September 11 attacks, we are seeing a very clear pattern of overly broad counterterrorism resolutions. We are seeing a clear pattern of violations on the ground that are being carried out in the name of complying with binding Security Council counterterrorism resolutions,” she added.

Just two weeks after September 11, 2001, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted Resolution 1373 which called states to adopt and implement measures to prevent and combat terrorism.

Since then, more than 140 countries have adopted counterterrorism laws.

The newly approved Resolution 2462, passed at the end of March, requires member states to criminalise financial assistance to terrorist individuals or groups “for any purpose” even if the aid is indirect and provided “in the absence of a link to a specific terrorist act.”

While the resolution does include some language on human rights protections, Tayler noted that it is not sufficient.

“It is not sufficiently spelled out to make very clear to member states what they can and cannot do that might violate human rights on the ground,” she said.

Blurred Lines

Among the major issues concerning these resolutions is that there is no universal, legal definition of terrorism, allowing states to craft their own, usually broad, definitions. This has put civil society organisations and human rights defenders (HRDs) alike at risk of detention and left vulnerable populations without essential life-saving assistance.

“I think it is irresponsible of the Security Council to pass binding resolutions that leave up to States to craft their own definitions of terrorism…that’s how you end up with counterterrorism laws that criminalise peaceful protest or criticising the state,” Tayler said.

Oxfam’s Humanitarian Policy Lead Paul Scott echoed similar sentiments to IPS, stating: “The Security Council, by being overly broad, is just giving [governments] the tools to restrict civil society.”

According to Front Line Defenders, an Irish-based human rights organisation, 58 percent of its cases in 2018 saw HRDs charged under national security legislation.

Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights while countering terrorism Fionnuala Ní Aoláin found that 67 percent of her mandate’s communications regarding civil society were related to the use of counter-terrorism, and noted that country’s counterterrorism laws are being used as a “shortcut to targeting democratic protest and dissent.”

In April 2018, thousands of people took to the streets in Nicaragua to protest controversial reforms to the country’s social security system.

According to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, over 300 people have been killed, more than 2,000 injured, and 2,000 arrested—some of whom were reportedly subject to torture and sexual violence when detained.

Many of those arrested will also be tried as terrorists due to a new law that expanded the definition of terrorism to include a range of crimes such as damage to public and private property.

At least 300 people, including human rights defenders, face charges of terrorism.

The Central American country said that the law was passed to comply with the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an intergovernmental body that works alongside the Security Council to combat terrorist financing.

A Civil Society Facing Uncivility

Tayler also pointed to the lack of consequences for States that pass counterterrorism laws that do not abide by their obligations under international law.

In Resolution 2462, member states are told to comply with international humanitarian law when cracking down on terrorist financing but does not require countries to consider the effect of such measures on humanitarian activities such as providing food and medical care.

“In the zeal to be as tough looking as they can possibly can, governments have overlooked very very easy ways to protect those of us who are providing life-saving aid,” Paul told IPS.

The lack of protections for civil society and its impacts was most visible during the 2011 famine in Somalia.

In an effort to restrict “material support” to terrorist groups, countries such as the United States enacted counterterrorism legislation which blocked aid into areas controlled by Al-Shabab.

This not only impeded local and international organisations from doing their job, but one report noted that the constraints contributed to the deaths of over 250,000 people in the East African nation.

The problem has only gotten worse since then, Paul noted.

“The measures imposed by governments are unnecessarily broad and they prevent us from working in areas that are controlled by designated terrorist entities. What they have essentially done is criminalise humanitarian assistance,” he said.

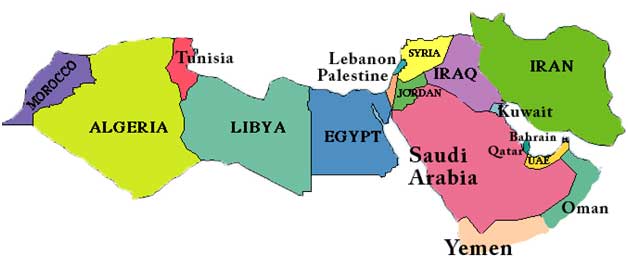

Tunisia has used its terrorism financing laws to shut down a number of civil society organisations.

According to the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor, approximately 200 organisations were dissolved and almost 950 others were delivered notices, referring them to courts on charges of “financial irregularities” or “receiving foreign funds to support terrorism” despite the lack of substantive evidence.

Many of the dissolved organisations provided aid and relief for orphans and the disabled.

All Eyes on Deck

Tayler highlighted the importance of the UN and civil society to monitor how counterterrorism resolutions such as Resolution 2462 are used on the ground.

“While we would love to see amendments to this resolution, pragmatically the next best step is for all eyes—the eyes of civil society, the UN, regional organisations—to focus on just how states implement this resolution to make sure that overly broad language is not used by states to become a tool of repression,” she said.

“The UN and leaders of countries around the world should use International Civil Society Week as an opportunity to take stock of the risk that this trend has posed on both to life-saving aid organisations and human rights defenders and to reverse this dangerous trend,” Tayler added.

Paul pointed to the need to educate both the public and policymakers on counterterrorism and its spillover effects as well as the importance of civil society in the global system.

“Civil society is a key part of effective governance. We don’t get effective public services, we don’t get peace, we don’t get to move forward with the anti-poverty agenda if civil society actors aren’t strong and empowered,” he said.

“If governments aren’t careful about protecting our right to stand up for marginalised and vulnerable populations, everyone will hurt. Not just those populations. It will have an effect broadly on our societies,” Paul added.

The truth was lost in this fierce political conflict and the Arab viewer had to cross-check the presented facts with other international reporting. This implicit bias and lack of balance polarized Arab public opinion and pushed news consumers to social media in search of trusted factual information, crushing the credibility in traditional media.

The truth was lost in this fierce political conflict and the Arab viewer had to cross-check the presented facts with other international reporting. This implicit bias and lack of balance polarized Arab public opinion and pushed news consumers to social media in search of trusted factual information, crushing the credibility in traditional media.