Civil Society, Democracy, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Global, Global Governance, Headlines, Inequity, Population, TerraViva United Nations

Tarik Gooptu is in his second and final year of the master’s of philosophy in economics at the University of Oxford. Originally from Washington, DC, he received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Michigan in economics and political science*.

– Tackling inequality in the 21st century requires us to understand and address barriers to upward mobility that segments of people face within countries. In a world with high and increasing levels of urbanization, the conversation on challenges to mobility must start with cities.

By addressing the drivers of inequality in cities, policymakers can alleviate conditions that perpetuate within-country inequality. Efficiently planning public transportation investments to target metropolitan communities with low connectivity is a crucial step to reducing disparities in upward mobility.

Doing this provides low-income residents with improved access to jobs, schools, hospitals, and other benefits of living in an urban area. A smart urban planning framework, enabled by effective partnership between the public and private sector, would enable citizens to enjoy a more level playing field.

As a result, cities can transform into drivers of global economic convergence in living standards.

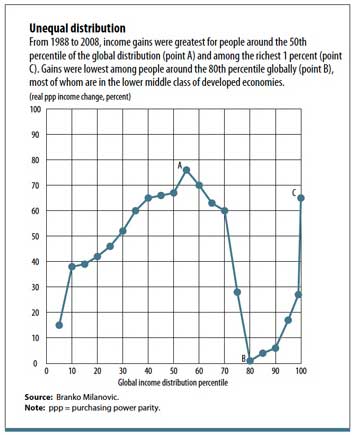

In the past three decades, the world has experienced a global convergence between countries, mainly due to increased international trade, advancements in technology, and economic integration.

However, these same factors have led to a relatively new phase of inequality seen in the 21st century. Works by Atkinson, Piketty, and Saez (2011) and Lakner and Milanovic (2016) have depicted a world suffering from inequality within countries, characterized by disparities between “gainers” and “losers” in the globalized economy.

People have proposed multiple explanations for this, including skill-biased technological change, increased automation, and outsourcing of jobs to regions with cheaper labor—to name a few. Perhaps somewhat overlooked are the large disparities between people living within the cities themselves.

Why cities? Rapid urbanization and severe intracity inequality are the two primary reasons policymakers should focus on cities when thinking about how to tackle the broader issue of inequality.

According to the World Urbanization Report, 55 percent of the global population resides in urban areas—an increase from 30 percent in 1950. The global urbanized population is projected to increase even further, to 68 percent, by 2050 (UN 2018).

In addition, the UN Population Division reports that “urbanization has been faster in some less developed regions compared to historical trends in the more developed regions” (UN DESA 2018. The convergence in the growth of urbanization, between developing and advanced economies, also suggests that the problems of cities increasingly affect countries at all income levels.

In addition to rapid urbanization, cities have become a locus of the most severe inequality we see today. A 2014 article by Kristian Behrens summarizes the issue of inequality within cities.

Behrens shows that within-country Gini indexes are highest as population densities increase and that under current conditions, cities tend to disproportionately reward people in the top income percentiles (Behrens 2014). In addition, cities draw people primarily from the top and bottom of the income distribution.

The global economic restructuring, outlined above, is expected to create more polarized income distribution within countries. This, combined with Behrens’s evidence, suggests that inequality within cities is expected to worsen, under current conditions.

The countries of the world are simultaneously experiencing unprecedented urbanization and severe inequality. While cities are currently the nexus of the worst inequality, there are opportunities to convert them into means for economic convergence.

The concept of “agglomeration economies” is summarized well by Edward Glaeser as the benefits realized from people and firms locating close to one another, in cities and industrial clusters, which are primarily gained through reduced transportation costs (Glaeser 2010).

But some areas in cities are not as well connected as others. This drives disparities between people in metropolitan localities. In order to address this, policymakers must address inequality of access to jobs and services between communities of different income status.

Underinvestment in roads, buses, train lines, and subways can cut off districts within large cities from jobs, education, and services. Higher mobility costs, in the form of longer commute times and lack of affordable transportation, are barriers to the upward mobility of lower-income people in cities.

Local governments and the private sector can work together to improve access to jobs and services by building a better public transportation infrastructure within cities. However, misallocation of both land and public resources worsens conditions for marginalized communities, contributing to intracity inequality.

The 2016 Rio Olympics, which have been heavily criticized for putting the city in an adverse fiscal situation, is as an example of how misallocation of public resources can actually perpetuate inequality in a city. Rio de Janeiro’s bus rapid transit (BRT) system is a designated-lane integrated bus system planned and funded via a public-private partnership.

City officials said that Rio’s BRT was needed to help transport Olympic spectators and will provide long-term rapid and affordable travel for city residents. While Rio’s BRT successfully reduced average transportation costs, its routes served to aggravate inequality between high- and low-income citizens.

An urban planning study conducted by the Fluminese Federal University shows how Rio’s major daily traffic flows run from lower-income neighborhoods (in the north and west) to downtown Rio (South Zone and part of the North Zone), where 60 percent of Rio’s formal employment is concentrated (Johnson 2014).

But, instead of providing lower-income residents access to the city center, the BRT allocates routes to an upper-income residential area. Jobs here are predominantly in the informal sector: not registered with the government, with lower salaries, and without health or other benefits.

Furthermore, the city government cut spending on health and police as a result of going over budget on Olympics expenditures, which worsened the health and safety of the poor.

Rio’s BRT system exemplifies how public infrastructure can be misallocated, without proper planning and an understanding of citizens’ demand for jobs and services. However, when policymakers implement well-planned public infrastructure, it can combat inequality within cities.

Curitiba’s BRT is a well-known example of effective urban planning yielding positive outcomes for city expansion. Planning of the bus line construction was orchestrated by the Institute for Research and Urban Planning of Curitiba in the 1970s.

Funding and implementation were conducted via a public-private-partnership between the Urban Development Agency of Curitiba, and private bus companies that operate the routes. The partnership model allows policymakers to develop creative ways to ease the cost burden of providing public infrastructure.

The result of Curitiba’s plan was a low-cost, fast, and efficient means of transportation, running on green energy, that has operated successfully for 35 years. A diagram from a 2010 World Resources Institute report shows that the integrated transit system provides a means for citizens in all areas of the expanding city to access all parts of it.

However, despite its initial success, even Curitiba’s sustainable transit system faces difficulties. A 2012 CityLab article says that in recent years, the city has failed to integrate its growing suburbs into its BRT system (Halais 2012).

As a result, low-income residents are cut off while upper-income residents switch to cars—an inconvenience for everyone that harms the poor more severely. Curitiba’s example shows that policymakers require a constant and proactive awareness of cities’ changing needs.

With available economic data and the implementation of origin-destination surveys, we can better understand where populations need to be connected and their demands for particular services.

An efficient way to tackle inequality is to address lack of mobility in cities, which drives unequal access to jobs, education, and services. Improving access to public infrastructure allows people of all income levels to benefit from the agglomeration effects of living in an urban area.

Well-planned public transportation systems bring cities closer to this goal through better access for low-income populations to jobs, schools, and hospitals in the city center. Thus, growing cities can serve as sources of economic convergence rather than divergence.

Public transportation not only helps lower inequality, it also helps reduce cities’ carbon footprint. As many megacities begin to suffer the ill effects of heavy pollution, policy that addresses both inequality and sustainability would be welcome.

*Following a global essay competition for graduate students on how best to tackle inequality, Tarik Gooptu’s submission was selected as the runner-up. To learn of future Finance & Development ( F&D) essay competitions, sign up for the newsletter here. F&D is a publication of the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Meanwhile, the lower middle classes in advanced economies saw their earnings stagnate.

Meanwhile, the lower middle classes in advanced economies saw their earnings stagnate.