Civil Society, Democracy, Featured, Global, Global Governance, Headlines, Human Rights, TerraViva United Nations

– The UN’s longstanding mandate to promote and protect human rights worldwide –- undermined recently by right-wing nationalist governments and authoritarian regimes – has taken another hit.

The Geneva-based Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) says six of the UN’s 10 treaty bodies are being forced to cancel their sessions this year due to financial reasons.

The situation has been described as “an unprecedented consequence of some UN member States delaying payments due to the Organisation.”

Anna-Karin Holmlund, Senior UN Advocate at Amnesty International (AI), told IPS: “Amnesty is deeply concerned by member states’ delay in paying their assessed contributions, which will have a direct effect on the ability of the UN to carry out its vital human rights work.”

Without these funds, the UN’s human rights mechanisms and International tribunals could be severely affected, she warned.

By 10 May, only 44 UN member states – out of 193 — had paid all their assessments due, with the United States owing the largest amount.

“Unfortunately, this is only the latest in a worrying trend of reduction in the UN budget allocated to its human rights mechanisms. To put this in perspective, the budget of the OHCHR is only 3.7 % of the total UN regular budget,” she pointed out.

In addition to the possible cancellation of sessions of the treaty bodies, mechanisms created by the Human Rights Council such as Fact-Finding Missions and Commissions of Inquiry may be hampered in carrying out their mandate of investigating serious human rights violations.

The OHCHR said last week the cancellations meant that reviews already scheduled with member states, as well as consideration of complaints by individual victims of serious human rights violations — including torture, extra-judicial killings, enforced disappearances -– will not take place as scheduled.

“The cancellation of sessions will also have numerous other negative consequences, and will seriously undermine the system of protections which States themselves have put in place over decades,” said a statement released by the OHCHR.

The chairpersons of the 10 Committees are deeply concerned about the practical consequences of cancelling these sessions and have sent a letter to the UN Secretary General and the High Commissioner for Human Rights, requesting they, together with Member States, explore ways of addressing this situation, “as a matter of urgency.”

Alexandra Patsalides, a Legal Equality programme officer at Equality Now, told IPS that it is deeply concerned that UN Treaty body review sessions have been postponed for financial reasons, including the Committee to Eliminate Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), with its focus on ending all forms of discrimination again women and girls.

She said the crisis comes particularly at a time when women’s rights are continuously being undermined and eroded around the world– and civil society organisations are operating in a space that is increasingly under attack and shrinking.

The UN should strongly call on state parties to prioritise their international human rights obligations, she added.

“The UN treaty bodies are vital to holding states accountable to their commitments on women and girl’s rights — and now is the time to increase the international response, not cut back,” said Patsalides.

These review sessions offer civil society organisations a vital opportunity to hold their governments to account for their international human rights commitments and raise awareness of human rights violations in their countries.

But with the backsliding on women’s rights across the globe, it is now more urgent than ever that the various mechanisms stand up to defend hard won gains, she noted.

“The UN treaty bodies are often the only mechanism for women and girls to hold their countries to account for violations of their rights. We cannot allow these voices to be silenced and call on the UN to prioritize the protection of women and girls’ rights and ensure these treaty bodies have appropriate and sustainable funding.”

The 10 UN human rights treaty bodies are: the Human Rights Committee, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, the Committee against Torture, the Committee on Migrant Workers, the Committee on Enforced Disappearances, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women, the Committee on the Rights of the Child, the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities And the Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture.

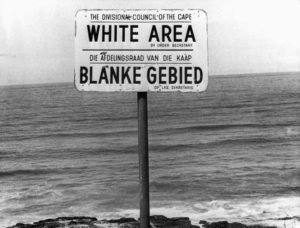

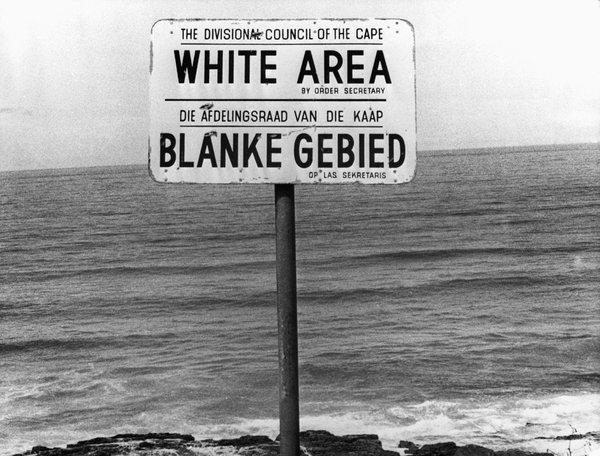

Meanwhile the budget cuts come at a time when the UN is battling a series of setbacks in the field of human rights.

The UN Human Rights Office in Burundi was closed down last February at the insistence of the government, with the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet expressing “deep regrets” over the closure, after a 23-year presence in the country.

A UN Commission of Inquiry has called on Eritrea to investigate allegations of extrajudicial killings by its security forces, including torture and enslaving hundreds of thousands, going back to 2016.

And under the Trump administration, the US has ceased to cooperate with some of the UN Rapporteurs, and specifically an investigation on the plight of migrants on the Mexican border where some of them have been sexually assaulted—abuses which have remained unreported and unprosecuted.

The government of Myanmar has barred a UN expert from visiting the country to probe the status of Rohingya refugees.

On the setbacks in Colombia, Robert Colville, Spokesperson for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, said May 10: “We are alarmed by the strikingly high number of human rights defenders being killed, harassed and threatened in Colombia, and by the fact that this terrible trend seems to be worsening”

“We call on the authorities to make a significant effort to confront the pattern of harassment and attacks aimed at civil society representatives and to take all necessary measures to tackle the endemic impunity around such cases.”

In just the first four months of this year, he pointed out, a total of 51 alleged killings of human rights defenders and activists have been reported by civil society actors and State institutions, as well as the national human rights institution.

The UN Human Rights Office in Colombia is closely following up on these allegations. This staggering number continues a negative trend that intensified during 2018, when our staff documented the killings of 115 human rights defenders.

According to a press release from the OHCHR, the 10 United Nations human rights treaties are legally binding treaties, adopted by the UN General Assembly and ratified by States.

Each Treaty establishes a treaty body (or Committee) comprising elected independent experts who seek to ensure that States parties fulfil their legal obligations under the Conventions.

This system of independent scrutiny of the conduct of States by independent experts is a key element of the United Nations human rights system, supported by secretariats in the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

The writer can be contacted at thalifdeen@ips.org