Asia-Pacific, Conferences, Development & Aid, Featured, Headlines, Health, Human Rights, Labour, Poverty & SDGs, TerraViva United Nations

Sandhya Mandal – a community health worker working on leprosy in Meherpur district of Bangladesh. Credit: Stella Paul / IPS

– Sandhya Mandal has never felt so vindicated. For the past four years, the 36-year-old community health worker from Meherpur – a rural district bordering India – has been traveling 50 km every day along dusty roads on an old motorbike, searching for leprosy patients who needed urgent treatment. But in her community, instead of compliments, neighbours and relatives raised questions about her work and her character. “They ask why I come home so late and what is this ‘work’ that I really do. Some even imply that I might be doing something like prostitution,” Mandal tells IPS.

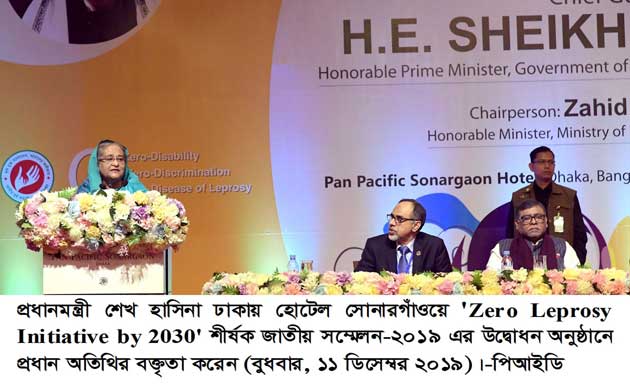

However, Mandal – project manager at an NGO called Shalom, which works with the government to end leprosy, sat in an audience of diplomats, ministers and health experts from all over the country, listening to Sheikh Hasina – the prime minister of Bangladesh – at a national conference on leprosy. “Nobody can doubt me or my work now,” she says, proudly clutching the yellow invitation card she received from the organizers of the conference – her first to a national-level event.

Mandal has every reason to be in the conference: since 2015 she has searched and found over 300 new leprosy cases. In fact, in November this year, she found 10 new cases on a single day – the result of an intense door-to-door search in Gangni, a small town with a high rate of leprosy. “We opened our database of old patients and contacted each one of them individually. We asked them if they knew anyone around them who had leprosy. Nobody could give us any concrete information, so I went from one house to other and from morning to evening I covered 40 families,” she recalls the drill. It was hard and Mandal did not have any time to eat or drink. But by day-end, she had found eight adults and two children who had visible signs of leprosy. She arranged for all of them to visit the TB and Leprosy Clinic (TLC) in Meherpur, a facility run by the government.

Early detection in leprosy key

Early detection and early treatment are the key to complete cure for anyone affected by leprosy, tells Mujibur Rahaman – a doctor at the TLC Meherpur. “The treatment is free. We have enough medicines. But bringing the affected ones to the treatment facility remains the biggest challenge,” Rahman tells IPS. Bangladesh eliminated leprosy in 1998, but new cases continued to be detected. In 2018, 3 729 new leprosy cases were detected.

Earlier this week, in her opening speech at the national conference, Prime Minister Hasina asserted that Bangladesh was committed to become leprosy-free by 2030. According to Rahman, dedicated community workers like Sandhya Mandal are the key to realizing the zero-leprosy status.

“Identifying a new patient is one thing; convincing them to see a doctor is entirely different. It takes very different level of skills,” he adds.

Providing counseling services

Mandal throws a little light on that skill: every time she finds a villager with a suspicious white patch with numbness, she tells him that it is a skin disease that needs urgent medical attention. “I never tell him it’s leprosy because, only a doctor can declare that after a test and also, if I spoke of leprosy, it would shock the person as everyone is still afraid of the disease,” Mandal reveals.

Mandal also counsels and provides emotional support to the person after a doctor has confirmed his or her leprosy. “Women are more scared than men because they feel their husbands will abandon them if they find out about their sickness. They are also scared of how their community would react. I tell them that they must tell their husbands but explain that its curable. To the neighbours, they can say it is a skin disease. I hold their hands, spend time with them. It calms them and it also makes them feel confident,” she tells IPS.

Listening to the prime minister has been an inspiring experience, Mandal says. At present there are not enough community health workers on leprosy. For example, in her own NGO, there are just two health workers. So, to achieve zero-leprosy in the next 10 years, Bangladesh would need many more community health workers, she says. Equipping the field workers at the rural NGOs with a motorbike would also help, as transportation remains a huge challenge in the villages. If these gaps are plugged, there is no reason why Bangladesh could not be leprosy-free, she says.

For those doubting her work, Mandal now has an answer: “Even the prime minister has shown an interest in leprosy, in our collective work. If anyone still doesn’t know why I work on leprosy for such long hours, they can ask the prime minister!”

The Nippon Foundation and the Sasakawa Health Foundation of Japan organized a national conference on leprosy in Dhaka on December 11 under the theme “ZeRo leprosy initiative”.