Civil Society, Democracy, Featured, Global, Global Governance, Headlines, Human Rights, TerraViva United Nations

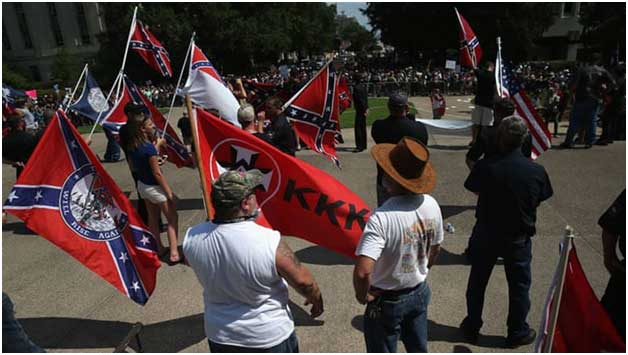

– The rise of right-wing nationalism and the proliferation of authoritarian governments have undermined human rights in several countries in Europe, Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Latin America.

As a result, some of the international human rights experts – designated as UN Rapporteurs – have either been politically ostracized, denied permission to visit countries on “fact-finding missions” or threatened with expulsion, along with the suspension of work permits.

The Philippines government, a vociferously authoritarian regime, has renewed allegations against Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, the UN Special Rapporteurs on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The Deputy Chief of Staff for Civil-Military Operations, Brigadier General Antonio Parlade, told reporters that the United Nations had been infiltrated by the Communist Party of the Philippines through Tauli-Corpuz.

But a group of UN human rights experts denounced the politically-inspired charges against a longstanding UN envoy on human rights.

“The new accusations levelled against Ms. Tauli-Corpuz are clearly in retaliation for her invaluable work defending the human rights of indigenous peoples worldwide, and in the Philippines,” the experts said

Anna-Karin Holmlund, Senior UN Advocate at Amnesty International, told IPS “We have witnessed several deeply worrying personal attacks by UN Member States against the independent experts, including personal attacks, threats of prosecution, public agitation and physical violence in the past year”.

“It is clear they are targeted for simply doing their job,” she added.

On occasion, she noted, these have been carried out by members of the UN Human Rights Council that are expressly required to uphold the highest standards in the promotion and protection of human rights.

“Such attacks are part of a disturbing trend of a shrinking space for human rights work more broadly in many places around the world,” declared Holmlund.

Meanwhile, the Government of Burundi has closed down the UN Human Rights Office triggering a protest from Michelle Bachelet, the UN Human Rights Commissioner in Geneva.

And under the Trump administration, the US has ceased to cooperate with some of the UN Rapporteurs, and specifically an investigation on the plight of migrants on the Mexican border where some of them have been sexually assaulted—abuses which have remained unreported and unprosecuted.

The government of Myanmar has barred a UN expert from visiting the country to probe the status of Rohingya refugees.

In March, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers, Diego García-Sayán, postponed an official visit to Morocco because the government “has not been able to ensure a programme of work in accordance with the needs of the mandate and the terms of reference for country visits by special procedures.”

He was scheduled to visit the country from 20 to 26 March “to examine the impact of measures aimed at ensuring the independence and impartiality of the judiciary and prosecutors, and the independent exercise of the legal profession.”

“It is most regrettable that the suggestions of places to visit and schedule of work were not fully taken into consideration by the Government. It is an essential precondition for the exercise of the mandate of Special Rapporteur that I am able to freely determine my priorities, including places to visit,” he said.

Referring to the situation in Colombia, Robert Colville, Spokesperson for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, said May 10: “We are alarmed by the strikingly high number of human rights defenders being killed, harassed and threatened in Colombia, and by the fact that this terrible trend seems to be worsening”

“We call on the authorities to make a significant effort to confront the pattern of harassment and attacks aimed at civil society representatives and to take all necessary measures to tackle the endemic impunity around such cases.”

In just the first four months of this year, he pointed out, a total of 51 alleged killings of human rights defenders and activists have been reported by civil society actors and State institutions, as well as the national human rights institution.

The UN Human Rights Office in Colombia is closely following up on these allegations. This staggering number continues a negative trend that intensified during 2018, when our staff documented the killings of 115 human rights defenders.

And last month, Israel revoked the work permit for Omar Shakir, the Israel and Palestine Director of Human Rights Watch, prompting a protest from the United Nations.

“This ruling threatens advocacy, research, and free expression for all and reflects a troubling resistance to open debate,” a group of UN experts said. “It is a setback for the rights of human rights defenders in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory.

Dr Palitha Kohona, a former chairman of the Israeli Practices Committee, mandated to monitor human rights violations in Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories, told IPS that official visits to the West Bank were barred by Israel (“and not for want of trying”) but not to Gaza, which they could not.

He said several approaches were made through the Israeli Missions in New York and Geneva to seek approval to interview persons on the ground in the West Bank, but to no avail.

“In 2011, we waited an extra day in Amman hoping to get approval which was never forthcoming. A ministerial visit by delegates from the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) to the West Bank was stopped at the Allenby Bridge by Israel”.

The Rafah crossing was controlled by Egypt and the Gaza authorities. Entry to Gaza for the Committee was through Sinai following a long bus ride from Cairo across the Sinai desert, said Dr Kohona, a former Permanent Representative of Sri Lanka to the United Nations.

“I visited Gaza twice in 2010 and 2011 with the Committee. I believe that these were the only two occasions that the Committee was able to visit Gaza.”

Egypt itself seemed to make the entry uncomfortable for the Committee, perhaps to keep Israel happy, he said.

In 2011, the Committee was held up for over four hours at the Rafah Crossing to Sinai. “Eventually I had to contact the Sri Lanka embassy in Cairo by phone to get us across”.

According to a report in the New York Times March 10, Leilana Farha, the UN Special Envoy for Housing was “shocked” to discover that some of the Egyptians she interviewed in Cairo’s poor areas “had suffered reprisals for talking to her.”

“Some were flung from their homes by officials, their belongings strewn in the streets. Others were harassed by the security services or barred from leaving Egypt,” said the report from New York Times correspondent Declan Walsh in Cairo.

“The foreign ministry accused Farha of fabricating stories and implied that she was a terrorist sympathizer, bent on smearing Egypt”.

The Times said “such defensive, conspiratorial talk is standard fare on Egypt’s television stations, which are heavily influenced by (Egyptian President) el-Sisi’s government. And it has seeped down into the street.

The United Nations currently has 38 Rapporteurs or independent experts appointed by the Human Rights Council in Geneva to investigate violations of the legitimate political, economic and legal rights of individuals and minorities worldwide going as far back as 1982.

These fact-finding missions, undertaken by UN Rapporteurs, cover a wide range of issues, including investigations into torture, extra-judicial killings, arbitrary executions, involuntary disappearances, racism, xenophobia, modern day slavery and the abuse of the rights of migrants and indigenous peoples.

Urmila Bhoola of South Africa, Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Slavery, told IPS she has visited Niger, Belgium, Nigeria, El Salvador, Mauritania, Paraguay and, lastly Italy, in October 2018.

She pointed out that “country visits are only conducted upon invitation from governments”.

“I have issued requests for country-visits to many countries but due to the mandate’s name and focus, member states are often reluctant to invite the mandate on contemporary forms of slavery, to conduct a visit”.

In this sense, she pointed out, member states may not openly refuse a visit but may not reply to country visit requests.

According to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, member states generally cooperate with the independent human rights experts in the Special Procedures of the Human Rights Council.

The number of States that have never received a visit by a mandate holder has diminished to 22. And the number of States that have issued a ‘standing invitation’ to Special Procedures has now reached 120 Member States and 1 non-Member Observer State.

Some States receive more than one visit per year. Each year, on average, Special Procedures conduct around 80 visits to different States.

At this time, said a spokesperson, “ we have not been notified of any changes concerning cooperation with Special Procedures by the United States’ Permanent Mission here in Geneva. Indeed, they have been in contact with several mandate holders recently”.

In December, 2017 the Government of Myanmar informed the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar that all access to the country has been denied and cooperation withdrawn for the duration of her tenure.

The writer can be contacted at thalifdeen@ips.org

The Ghanaian government needs to protect our country and beautiful culture

The Ghanaian government needs to protect our country and beautiful culture