Aid, Armed Conflicts, Asia-Pacific, Children on the Frontline, Civil Society, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Education, Featured, Headlines, Human Rights, Migration & Refugees, Sustainable Development Goals, TerraViva United Nations

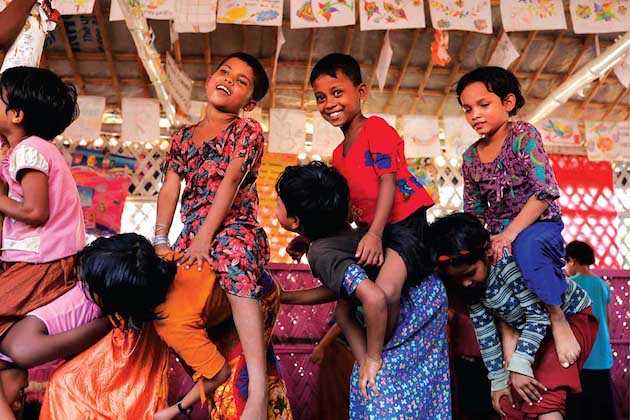

A young child in Cox’s Bazar engages with her peers at one of BRAC’s Humanitarian Play Labs. CREDIT: BRAC

– A Rohingya woman tells a forum of peer counselors the story of her divorce. A survivor of domestic abuse, she has started a new life alone with her daughter. She has weathered a storm of neighbors telling her she was the problem. Now, she provides the support she didn’t have to other women like her.

Similar scenes occur across refugee camps in Cox’s Bazar. Here, BRAC, an international NGO based in Bangladesh, has developed a program to train counselors who can provide mental health services to Rohingya refugees. This includes 200 community members who have begun to practice the psychosocial skills they’ve learned in their own lives.

A Growing Need for Support

Over 900,000 Rohingya have fled to Cox’s Bazar since massive-scale violence against Rohingya in Myanmar’s Rakhine State began in 2017, the UN Refugee Agency reports. The prolonged exposure of the ethnic minority group to persecution and displacement has likely increased the refugees’ vulnerability to an array of mental health issues, a 2019 systematic review found. Their struggles include post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and gender-based violence.

Around the world, there is growing attention to the importance of socio-emotional learning as a skill to help people in areas of crisis cope with challenges. Educators are often tasked not only with providing traditional academic instruction but with building resilience in children. They are asked to create a sense of normalcy in environments that are anything but normal.

The teaching the children need is much more than about reading, writing, and math; but about giving young children a safe space to practice socio-emotional skills. CREDIT: BRAC

“It’s about not only teaching [kids] how to read and how to do mathematics … in these settings, kids and teachers themselves have the need for psychosocial support,” Ramya Vivekanandan, the senior education specialist at the Global Partnership for Education, said.

Teachers, caregivers, and frontline mental health providers are overburdened, Vivekanandan explains. They lack adequate pay, working conditions, and professional development. As they try to support the growing number of people in crisis, who will support them?

For some counselors in Cox’s Bazar, the answer is each other.

Community Care

Even when resources are available, stigmas around mental health can prevent support from being received. Taifur Islam, a Bangladeshi psychologist responsible for mental health training and supervision at BRAC, says people in the communities he works with are rarely taught to identify their feelings. When you are struggling to access basic needs, Islam explains, it is easy to forget that emotional well-being can improve productivity. If a person seeks help, they may be labeled ‘crazy.’

Training people to take care of their own communities can be a powerful way to overcome stigma in a culturally relevant way.

BRAC’s Humanitarian Play Labs were established in 2017 to give Rohingya children a safe space to practice socio-emotional skills through play. Erum Mariam, the executive director of the BRAC Institute of Educational Development, explains that each play lab is tailored to fit the community it serves. Rohingya children now rhyme, chant, and dance in 304 Humanitarian Play Labs across the camps in Cox’s Bazar.

“We discovered the Rohingya culture through the children. And the whole model is based on knowing the culture,” Mariam said.

‘Play leaders’ are recruited from the camps and trained in play pedagogy. Mariam watched Rohingya women who had never worked before embracing their new roles. As they covered the ceilings of their play spaces with rainbows of flowers – the kind of tapestry that would hang from their homes in Myanmar – Mariam realized that a new kind of social capital could be earned by nurturing joy. Traditional play didn’t just help uprooted children shape their sense of identity – it was also healing for the community.

If a play leader notices a child is withdrawn or restless, they can refer the child to a ‘para counselor’ who has been trained by BRAC’s psychologists to address the mental health needs of children and their family members. Almost half of the 469 para counselors in Cox’s Bazar are recruited from the Rohingya community, while the rest come from around Bangladesh. Most para counselors are women.

Many para counselors are uniquely positioned to empathize with the people they serve as they go door to door, building awareness. This is crucial because it creates a bottom-up system of care without prescribing what well-being should look like, Chris Henderson, a specialist on education in emergencies, says.

At the same time, by supporting others, mental health providers are learning to take care of themselves.

Learning by Doing

A play leader engages the children in the session. Humanitarian professionals encourage frontline teachers, caregivers, and counselors to actualize their own ideas for improvement. CREDIT: BRAC

For months, Suchitra Rani watched violence against Rohingya people every time she turned on the news. When she was recruited by BRAC to become a para counselor in Cox’s Bazar, she saw an opportunity to make a difference. Alongside fellow trainees, Rani, a social worker originally from Magura, poured over new words she learned in the foreign Rohingya dialect and worked to find her place in the community.

Rani tested what she had learned about the value of psychosocial support and cultural sensitivity when she met a 15-year-old Rohingya girl too scared to tell her single mother she was pregnant. Terrified of bringing shame to the family, the girl had an abortion at home. As the young woman spiraled into depression, Rani felt herself slipping into her own fears of inadequacy.

It took time for Rani to convince the girl to open up to her mother. Talking through feelings of guilt slowly led to acceptance. As they worked to heal fractured family bonds, Rani began to feel surer of herself, too.

Now, the Rohingya community calls Rani a “sister of peace.” Rani says she has become confident in her ability to use the socio-emotional skills she’s learned to both help others and resolve problems in her personal life.

Throughout the program, para counselors have changed the way they communicate their feelings and felt empowered to create more empathetic environments.

Islam recounts a 26-year-old Rohingya refugee’s perilous journey to Cox’s Bazar: In Myanmar, the woman’s husband was killed in front of her. One of her two young children drowned during a river crossing as they fled the country. She arrived at the camp as a single mother without a support network. Only once she had the support of others willing to listen could she speak openly.

Islam remembers counselors telling the woman about the importance of self-care: “If you actually take care of yourself, then you can take care of your child also.”

Toward Empowerment

According to Henderson, evidence shows that one of the best ways to support someone is to give them a role to help others. In places where there may be a stigma against prioritizing ‘self-care,’ people with their own post-crisis trauma are willing to learn well-being skills to help children.

A collection of teacher stories collected by the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies reveals a similar pattern. Teachers in crisis areas around the world say the socio-emotional skills they learned to help students helped them reduce stress in their own lives, too.

Henderson suggests that the best way international agencies can promote trauma support is by holding up a mirror to the strength already shown by refugee communities like the Rohingya.

Instead of seeing what they lack, Henderson encourages humanitarian professionals to help give frontline teachers, caregivers, and counselors the agency to actualize their own ideas for improvement. Empowered community leaders empower the young people they work with, who, in turn, learn to empower each other. This creates “systems where everyone sees their position of leadership as supporting the next person’s leadership and resilience.”

At the end of her para counselor training, the Rohingya domestic abuse survivor said she wasn’t sure what she would do with the skills she’d learned for working through trauma, Islam remembers. But she did say she wished they were skills she had known before. According to Islam, she is now one of their best para counselors.

“The training is not only to serve the community; that training is something that can actually change your life,” Islam says. It’s why he became a psychologist.

IPS UN Bureau Report