Armed Conflicts, Civil Society, Crime & Justice, Democracy, Education, Featured, Gender, Global, Global Governance, Headlines, Human Rights, Inequity, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, Peace, TerraViva United Nations, Women in Politics

Ambassador Anwarul K. Chowdhury, former Under-Secretary-General and High Representative of the United Nations and Founder of The Global Movement for The Culture of Peace (GMCoP), was the keynote speaker at the observance of the International Day of Non-Violence on the 15th Mahatma Gandhi Day Celebration, organized virtually by the Gandhi International Institute for Peace (GIIP)

Credit: United Nations

– I will begin by presenting to you excerpts from the message from UN Secretary-General António Guterres on the International Day of Non-Violence.

I quote: “In marking the birthday of Mahatma Gandhi, this International Day highlights the remarkable power of non-violence and peaceful protest. It is also a timely reminder to strive to uphold values that Gandhi lived by: the promotion of dignity; equal protection for all; and communities living together in peace.

On this year’s observance, we have a special duty: stop the fighting to focus on our common enemy: COVID-19. There is only one winner of conflict during a pandemic: the virus itself. As the pandemic took hold, I called for a global ceasefire. Now is the time to intensify our efforts. Let us be inspired by the spirit of Gandhi and the enduring principles of the UN Charter.” End of quote

At the outset, let me thank the Gandhi International Institute for Peace (GIIP) and its dynamic President Mr. Raj Kumar for organizing the observance of the International Day of Non-Violence and of the 15th Mahatma Gandhi Day Celebration by the Institute.

The theme of my keynote speech today is “Mahatma’s Non-Violence: Essence of The Culture of Peace for New Humanity”

The Mahatma affirmed that he was not a visionary but a practical idealist. He affirmed that “Non- violence is the law of our species, as violence is the law of the brute. The spirit lies dormant in the brute and he knows no law but that of physical might. The dignity of man requires obedience to a higher law – to the strength of the spirit.”

It is said that “he was the first in human history to extend the principle of non-violence from the individual to the social and political plane.” He entered politics for the purpose of experimenting with non-violence and establishing its validity.

Ambassador Chowdhury

The Mahatma had said that “Nonviolence is the greatest and most active force in the world. One cannot be passively nonviolent … One person who can express ahimsa in life exercises a force superior to all the force of brutality.” I believe whole-heartedly that Mahatma Gandhi’s principle of nonviolence or Ahimsa has found true reflection in the life of a great son of the United States, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s own struggle for equality and justice.

Dr. King considered his Nobel Peace Prize as “a profound recognition that nonviolence is the answer to the critical political and racial questions of our time – the need for man to overcome oppression without resorting to violence“. I reiterate this mainly to highlight the need for revisiting those words in view of what is happening in many parts of our world, including in this country.

As I have stated on many occasions, my life’s experience has taught me to value peace and non-violence as the essential components of our existence. Those unleash the positive forces of good that are so needed for human progress. Peace is integral to human existence — in everything we do, in everything we say and in every thought we have, there is a place for peace.

It is important to realize that the absence of peace takes away the opportunities that we need to prepare ourselves, to empower ourselves to face the challenges of our lives, individually and collectively. This intellectual and spiritual inspiration is implanted in me through the Mahatma’s life and his words.

The United Nations Charter emerged in 1945 out of the ashes of the Second World War. The UN Declaration and Programme of Action on Culture of Peace was born in 1999 in the aftermath of the Cold War. I was the chair of the nine-month-long negotiations from 1998 to 1999 that produced the Programme of Action on Culture of Peace.

For more than two decades, I have continued to devote considerable time, energy and effort to realizing the implementation of this landmark, norm-setting decision of the UN. For me, this has been a realization of my personal commitment to peace inspired by the Mahatma and my humble contribution to humanity.

My work took me to the farthest corners of the world and I have seen time and again how people – even the humblest and the weakest – have contributed to building the culture of peace in their personal lives, in their families, in their communities and in their countries – all these contributing to global peace one way or the other.

The focus of my work and advocacy has been on advancing the culture of peace which aims at making peace and non-violence a part of our own self, our own personality – a part of our existence as human beings. I believe this will empower ourselves to contribute more effectively to bring inner as well as outer peace.

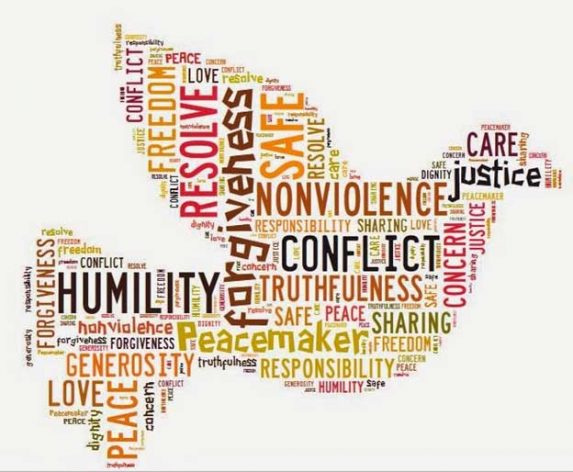

In simple terms, the Culture of Peace as a concept means that every one of us needs to consciously make peace and nonviolence a part of our daily existence. We should know how to relate to one another without being aggressive, without being violent, without being disrespectful, without neglect, without prejudice.

We should not isolate peace as something separate or distant. More so, in today’s world so full of negativity, tension, poverty and suffering, the culture of peace should be seen as the essence of a new humanity, a new global civilization based on inner oneness and outer diversity.

In my keynote address on “Human Security – an Essential Element for Creating the Culture of Peace” at the Victoria University in Wellington, New Zealand, in August 2007, inspired by Mahatma’s eternal words “Be the change that you want to see in the world,” I underscored that “Peace is a prerequisite for human development.… We all must undertake efforts to inculcate the culture of peace in ourselves. We cannot expect the world to change if we do not start first and foremost with changing ourselves – at the individual levels.”

The objective of the culture of peace is the empowerment of people, as has been underscored by the global leader for peace and Buddhist philosopher Daisaku Ikeda. As we say “Peace does not mean just to stop wars, but also to stop oppression, injustice and neglect”. The culture of peace can be a powerful tool in promoting a global consciousness that serves the best interests of a just and sustainable peace.

I am encouraged that the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted by the UN in 2015 includes, among others, the culture of peace and non-violence as well as global citizenship as essential components of today’s education.

This realization has now become more pertinent in the midst of the ever-increasing militarism and militarization that is destroying both our planet and our people. The Mahatma asserted that “One thing is certain. If the mad race for armaments continues, it is bound to result in a slaughter such as has never occurred in history. If there is a victor left, the very victory will be a living death for the nation that emerges victorious. There is no escape from the impending doom save through a bold and unconditional acceptance of the nonviolent method with all its glorious implications.”

Dr. King had advised us rightly, “… I suggest that the philosophy and strategy of nonviolence become immediately a subject for study and for serious experimentation in every field of human conflict, by no means excluding the relations between nations.”

The last decades of violence and human insecurity should lead to a growing realization in the world of education today that children should be educated in the art of peaceful, non-violent, non-aggressive living.

Never has it been more important for the next generation to learn about the world and understand and respect its diversity. I want to underscore one particular aspect in this context. In the culture of peace movement, we are focusing more attention on children because that contributes in a major way to the sustainable and long-lasting impact on our societies. As the Mahatma’s words highlight, “Real education consists in drawing the best out of yourself.”

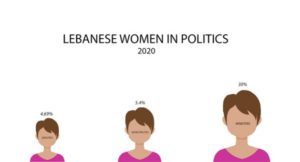

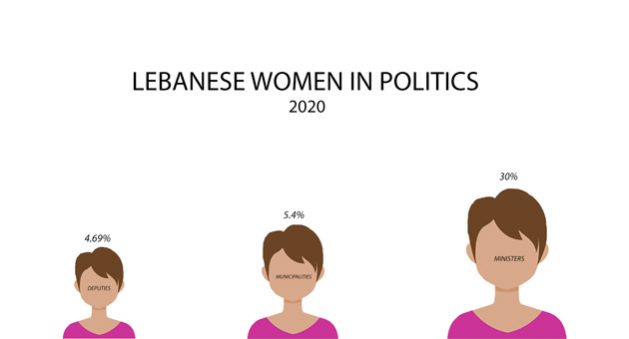

An essential message that I have experienced from my work for the culture of peace is that we should never forget that when women – half of world’s seven plus billion people – are marginalized, there is no chance for our world to get sustainable peace in the real sense.

Women bring a new breadth, quality and balance of vision to a common effort of moving away from the cult of war towards the culture of peace. “Without peace, development cannot be realized, without development, peace is not achievable, but without women, neither peace nor development is possible.”

I believe the culture of peace is not a quick-fix. It is a movement, not a revolution.

Let us remember that the work for peace is a continuous process. Each one of us can make a difference in that process. The culture of peace cannot be imposed from outside; it must be realized from within.