I married my cousin. Before you judge me, let me explain. We are divorced (unrelated to above confession) but remain great friends — could this be because of a warm, familiar connection?

Much hilarity about this discovery aside, we are only seventh cousins, which means there are a few hundred years between us and our common ancestor. This might sound alarming but, apparently, if you still live in the general area your relatives did, it’s likely you have met, and perhaps even married, a distant cousin.

Start looking into your genealogy, the study of ancestors and family history, and you are sure to find a skeleton or 10 in your closet.

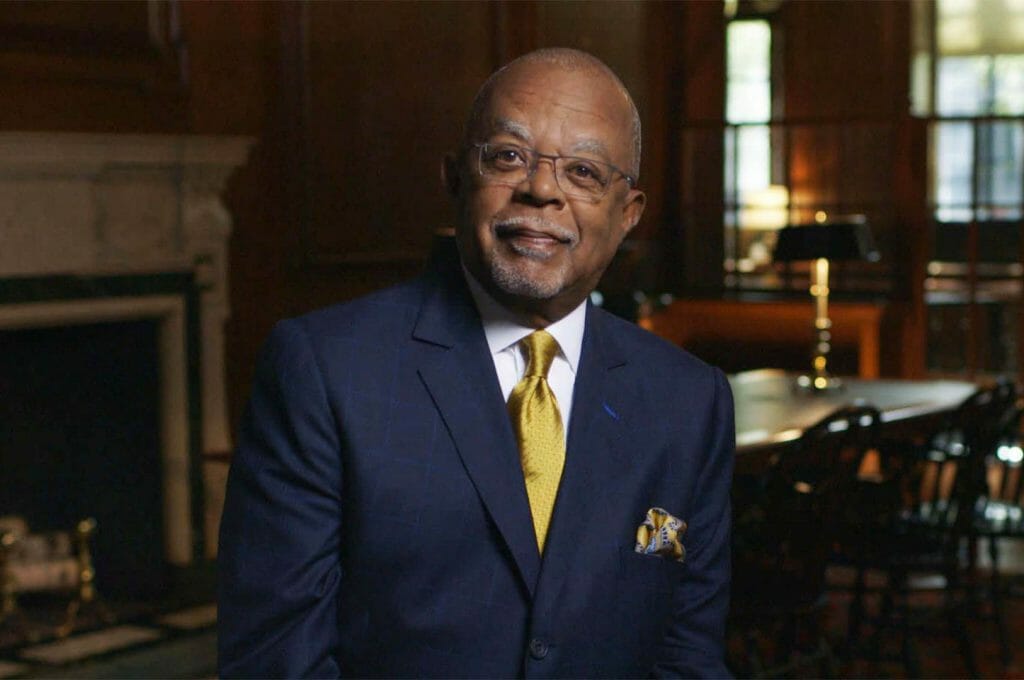

I started my genealogy journey in 2019, inspired by the TV series Finding Your Roots. It is the creation of historian Henry Louis Gates, director of the Hutchins Centre for African and African American Research at Harvard in the US. His interest in genealogy came from the 1977 miniseries Roots. It made him dream of finding his African ancestry and helping other people do the same — not easy, because much African American ancestry is unknown and only found in slave-ownership records.

Finding Your Roots is a fascinating investigation into the lineage of well-known Americans, including artist Kara Walker, politician Condoleezza Rice and comedian Andy Samberg. Using records and DNA analysis, it shows humanity at its best and worst. Often focusing on slavery and African-American heritage, it is a sensitive study of the importance of understanding the past and where you came from.

Following the line

My family tree is still a work in progress but I have unearthed fascinating stories that are interwoven with South Africa’s past.

I learnt that the women in my family were unbelievably brave and strong. Case in point, my three times great-grandmother, Margaret, was a “Kennaway Girl”. This group of 150 young Irish women were given the name because they travelled to South Africa on the Lady Kennaway ship in 1857 to start a new life as wives for a group of German former soldiers who’d settled in the Eastern Cape.

I also discovered my two times great-grandmother, Mimi, died in an Anglo-Boer War concentration camp.

Then there was proving who an illegitimate relative’s mother was. For the first time in 118 years, we proudly added her to our family tree.

Court documents showed this courageous woman sued a man who promised marriage, seduced her, and left her pregnant. Scandalous in conservative 1904, she took him for everything he was worth, including a buggy and some sheep.

Having recently lost my father, I’m grateful we could build our family tree together while he was still alive.

Do it yourself

If you’re feeling inspired to do some ancestral digging of your own, there are some practical places to start. My first step was to start a free account on familysearch.org. This non-profit platform is the world’s largest shared family tree, dedicated to helping people discover their family story. The site lets you build your own tree and puts millions of digitised records at your fingertips.

FamilySearch.org is owned and run by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS). They have a deep involvement in genealogical research and believe it’s essential for people to strengthen relationships with family members (alive or dead), so they can be together after this life.

Wayne van As, FamilySearch Southern Africa’s area manager, says: “We go out and negotiate with governments, churches and archives for their records. We then provide them with a mutually beneficial agreement and basically preserve their records. We also provide them with a digital donor copy of everything that we digitised for them, in exchange for allowing us to put these records on familysearch.org.”

An alternative to FamilySearch is ancestory.com, the world’s largest for-profit genealogy company. Although it is pricey — it costs up to $60 (R1 000) a month — it offers over 30-billion records, including census, military and immigration records. Chatting to older family members — even if their memories are vague — was useful, because there is generally some truth in what they recall.

Googling historic events that acted as a backdrop for my ancestors’ stories helped, as did online national archives. The result — my family tree now runs to the 1400s. I also did a course with Natalie da Silva of the Joburg branch of the Genealogical Society of SA. This is a great introduction to the extensive archives and records available, especially for those who are not comfortable with online searches and apps.

If research isn’t your thing, you can hire an expert to put in the hard miles.

Heather MacAlister, a respected family tree and genealogy researcher, runs ancestors.co.za. Of her work she says: “Clients come to me for all sorts of reasons. From helping people who are adopted to try and source original birth entries that home affairs can’t find, to naturalisations, to working with film companies to do research. And even aiding probate lawyers from around the world looking for heirs in South Africa.”

Not so easy

It would be remiss not to discuss what this ancestral-tracing process is like for black South Africans. When I spoke to friends of colour, a general thread was that they knew very little, despite having strong family stories and a tradition of family names.

This got me thinking about what colonial and apartheid records are like for people of colour and what effect the migrant labour system and cross-border migration had on the genealogical record. I tried researching two friends’ families, one Pedi from Limpopo, the other coloured, from Johannesburg. This was harder than researching my own line — the paper trail is severely limited.

MacAlister explains, “One also needs to distinguish between black and coloured and Indian. For example, coloured is much easier [to trace] than black ancestry.”

Most experts I chatted to had seldom been asked to research people of colour’s families. On this point, Van As says: “For a long time, people of African descent didn’t think records were kept but they were. If a person of colour had an estate, or if they have left something behind, their last will and testament is recorded at the master’s office.”

The department of home affairs also has records, such as death notices, births and marriages, of African people. There are lots of sources of African records if you know where to look but, too often, people focus on European descent.

Da Silva has been working on compiling a database of indigenous marriages in early Johannesburg. And FamilySearch is always looking for opportunities to digitise records. Van As says a good example of this is the apartheid-era “dompas”, or pass, records which the LDS church has been trying to track down for years, having heard there are shipping containers full of them somewhere.

Van As advises a good way to get started is to contact family members.

“Go back to the family village and sit down with the village elders to discuss your family. Find out who the first ancestors were and gather as much info as possible. Of course, bearing in mind many people have migrated from villages to the city, and don’t go back to their homes often.

“Once you have that info, you can start adding it to familysearch.org.

“If you are allowed to, record the elders speaking — oral history recordings are important as it’s normally done in people’s own language.”

The LDS church has long recognised the significance of oral record-keeping. FamilySearch has been gathering oral histories in Africa for years, in over 14 countries and are expanding and looking to expand to several countries, including Malawi, Zambia and, hopefully, South Africa.

“We have just done our millionth interview and from that preserved over 170-million names of people and their ancestors. This is something we are trying to do, so that we can provide an experience on FamilySearch for people that can’t get back to their villages, so then the village will come to them,” says Van As.

He added, “We have over 10 000 field agents, who go to villages and do the interview on a cellphone. They also take a picture of the person, their family and the village. So, you have the pictures and audio. We then print out and bind all the info we have recorded, giving a copy back to the village and community.”

Cracking the code

Archival and oral history research go hand in hand with a DNA test.

“The paper trail can be full of errors, so having your DNA tested will complement your paper research,” MacAlister says, “especially if you don’t know who your parents, grandparents or great-grandparents were.”

She recommends doing this on ancestry.com as it’s the best for an autosomal DNA test. Once you have got the results, you can download your DNA and upload it to platforms like MyHeritage, FamilyTreeDNA and GEDmatch, where you will find even more DNA matches.

The implication of DNA research is widespread and surprising. For example, the Continuum Project uses genetic science and the arts to explore the identity of African American children who descend from enslaved people. By testing their DNA, they can pinpoint where in Africa they originate from and instil pride in their heritage.

So, skeletons in the closet aside, researching your heritage, whether through oral history, archives or studying genetic makeup, is valuable. After learning about his ancestors on Finding Your Roots, actor Leslie Odom Jr said his search had led to a reimagining of himself. I couldn’t agree more — the roots of your family tree are like an anchor, keeping you steady in a storm.