Civil Society, Featured, Global, Headlines, Health, Human Rights, Humanitarian Emergencies, Inequity, TerraViva United Nations

Abby Maxman is President & CEO of Oxfam America

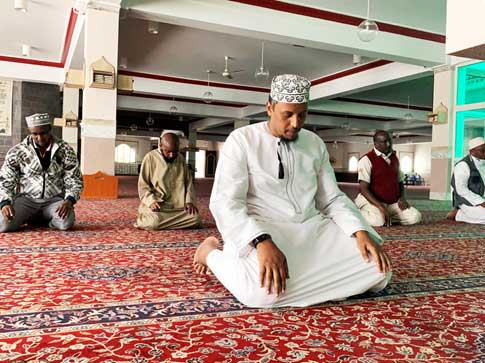

Credit: Oxfam America

– NGOs, at the international, national – and most of all local – level are on the frontlines every day.

I just heard from Oxfam staff in Bangladesh, that when asked whether they were scared to continue our response with the Rohingya communities in Cox’s Bazar, they replied: “They are now my relatives. I care about them — and this is the time they need us most.’”

These people – and those that they and others are supporting around the globe – are at the heart of this crisis and response.

As we talk about global figures and strategies, we must remember we are talking about parents who must decide whether they should stay home and practice social distancing or go to work to earn and buy food so their children won’t go hungry; women who constitute 70% of the workers in the health and social sector globally; people with disabilities and their carers; those who are already far from home or caught in conflict; people who don’t know what information to believe and follow, as rumours swirl.

Looking more broadly, we see that the COVID-19 crisis is exposing our broken and unprepared system, and it is also testing our values as a global community. COVID-19 is adding new and exacerbating existing threats of conflict, displacement, gender-based violence, climate change, hunger and inequality, and too many are being forced to respond without the proper resources – simple things like clean water, soap, health care and shelter. We must be creative and nimble to adapt our response in this new reality.

Most vulnerable communities

We know too well that when crisis hits, women, gender diverse persons, people with disabilities and their carers, the elderly, the poor, and the displaced suffer the worst impacts as existing gender, racial, economic and political inequalities are exposed.

Abby Maxman

These communities need to be at the center of our response, and we, as the international community, must listen to their needs, concerns and solutions.

Access

As we continue to ramp up our response, we must have access to the communities most in need. Likewise, COVID-19 cannot be used as an excuse to stop those greatest in need from accessing humanitarian aid.

Border closures are squeezing relief supply and procurement chains; Lockdowns and quarantines are blocking relief operations; And travel restrictions for aid workers have been put in place, disrupting their ability to work in emergency response programs.

Authorities should absolutely take precautions to keep communities safe, but we need to work at all levels to also ensure life-saving aid can still get through and people’s rights are upheld.

Local and national NGOs are on the frontline of the COVID-19 response, and communities’ access to the essential services and lifesaving assistance they provide must be protected. We also know that with effective community engagement, we can gain better and more effective access to communities.

Humanitarian NGOs and partners are adapting our approaches to continue vital humanitarian support while fulfilling our obligation to “do no harm.”

This adaptive approach, and our experience of ‘safe programming,’ shifting to remote management where possible; and scaling back some operations where necessary—will all be crucial as COVID-19 restrictions continue to amplify protection concerns and risk of sexual exploitation and abuse.

Funding

To mount an effective response, we must draw on our collective experience, but this crisis also offers an opportunity to change the way we work, including setting up new funding mechanisms to allow our system to leverage the complementary roles we all play in a humanitarian response.

Overall, NGOs urgently need funding that is flexible, adaptive, and aligned with Grand Bargain commitments. Our work is well underway, but more is needed to get resources to the frontlines.

We need to better resource country based pooled funds, which are crucial for national and local NGOs. Now more than ever, donors must support flexible mechanisms to increase funding flows to NGO partners.

Next Steps

In closing, the international community needs to come together to battle this pandemic in an inclusive and a responsive way that puts communities at the heart of solutions. Even while we respond in our own communities, we must see and act beyond borders if we are ever to fully control this pandemic.

The planning and response to COVID-19 need to be directly inclusive of local and national NGOs, women’s rights organizations, and refugee-led organizations leaders. We must address this new threat, while still responding to other pressing needs for a holistic response.

This means continuing our response to the looming hunger crisis, maintaining access to humanitarian aid, and supporting existing services including sexual and reproductive health and gender-based violence services.

We need to ensure humanitarian access is protected to reach the most vulnerable.

And funding needs to be quickly mobilized through multiple channels to reach NGOs and must be flexible both between needs and countries.

This much is clear: We cannot address this crisis for some and not others. We cannot do it alone. The virus can affect anyone but disproportionately affects the most marginalized. It is our collective responsibility to ensure that our global response includes everyone.

We owe it to those dedicated staff and their honorary “relatives” in Cox’s Bazar, and all those like them around the globe, to get this right.

This article was adapted from Abby Maxman’s comments as the NGO representative at the UN’s Launch of the Updated COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan on May 7, 2020.