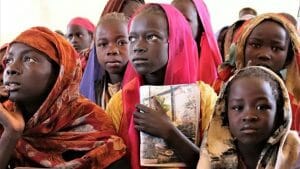

Shabana Basij-Rasikh, co-founder and President of SOLA, speaks at the Women Deliver conference in Rwanda. Credit: Aimable Twahirwa/IPS

By Aimable Twahirwa

KIGALI, Aug 1 2023 (IPS)

When providing education to her small group of Afghan girls, who had been studying at a boarding school back home, became tenuous, Shabana Basij-Rasikh, relocated them to Rwanda.

She had set up a pioneering school under the project SOLA, the Afghan word for peace, and a short form for School of Leadership Afghanistan. But as the Taliban swept to power in August 2021, she closed the doors of the school, destroyed any school records which could help identify the girls, and on August 25, relocated 250 members of the SOLA community, including the student body and graduates from the programme, totally more than 100 girls, to Rwanda.

Basij-Rasikh, co-founder and SOLA’s President said a major challenge had been the lack of resources and capacity to teach Afghan girls after the return of the Taliban deprived right to education of girls in secondary schools and above.

As the Taliban swept back into power in Afghanistan in the summer of 2021, Shabana Basij-Rasikh, the founder of the nation’s only all-girls boarding school, initially ran the school out of a former principal’s living room. But that soon became untenable.

Speaking on the sidelines of The Women Deliver 2023 Conference (WD2023), which took place in Kigali from 17-20 July 2023, Basij-Rasikh, who completed her undergraduate studies in the United States, explained that when Kabul fell under the control of the Taliban, she managed within a short time to evacuate the entire school community to Rwanda.

“Although we managed to move the school to a safe country, it is still embarrassing and shameful for me since Afghanistan is the only country in the world where women and girls’ access to education has been suspended,” she said.

Initially, SOLA started as a scholarship program where Afghan youth would be identified and could access quality education abroad and, later on, go back to their home country as highly-skilled Afghans in whichever profession they chose.

“When the US announced that they were to withdraw their troops in Afghanistan, it created a lot of anxiety among young Afghans who were in the West hoping to return to the country.”

Basij-Rasikh regrets that some of her former students, who were able to leave Afghanistan after the Taliban’s return, are still struggling to continue their education overseas.

“We wish to see many Afghan girls return to schools,” she said, explaining that the migration status of the students in many countries restricted their access to education.

Since the school opened last year’s admissions season, Shabana Basij-Rasikh and her team have been inviting Afghan girls worldwide to apply and join the rest in Rwanda. Last year they enrolled 27 girls in their first intake.

“The major challenge is that there are several hundreds of thousands of girls who want to join our campus, but space is limited, and so places are being granted on merit and need,” Shabana told IPS.

Shabana argues investing in girls’ education is a smart investment; she is convinced that the current situation in Afghanistan must and should not be accepted or supported by any country around the world.

On September 18, 2021, a month after taking over the country, the Taliban ordered the reopening of only boys’ secondary schools. A few months later, in March 2022, according to human rights organizations, the Taliban again pledged to reopen all schools, but they officially closed girls’ secondary schools.

“These girls deserve the opportunity to realize their full potential, and the international community has an important role to play,” Shabana said.

UNESCO’s latest figures show that 2,5 million or 80 percent of school-aged Afghan girls and women are out of school. The order suspending university education for women, announced in December last year, affects more than 100,000 students attending government and private institutions, according to the UN agency.

On the sidelines of the Women Deliver Conference 2023, Senegalese President Macky Sall pledged that his government would offer 100 scholarships for women who have seen their right to education decimated under Taliban rule in Afghanistan to pursue their university degrees in Senegal.

Rwanda is one of several African countries that agreed to temporarily host evacuated Afghans.

Sall, who was reacting to the concerns raised by Basij-Rasikhat, said his Government was ready to give chance to Afghan girls to pursue their studies.

So far, SOLA school has received 2,000 applications across 20 countries where some Afghans are living.

In 2022, it received 180 applications from Afghans living in 10 countries, but only 27 girls were admitted.

“That explains how families in Afghanistan are ready to support the girls in moving abroad to pursue their education,” Shabana said.

“Boarding schools that allow Afghan girls to study and live together are the best way to promote their education.”

IPS UN Bureau Report