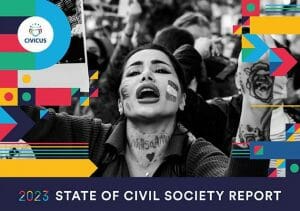

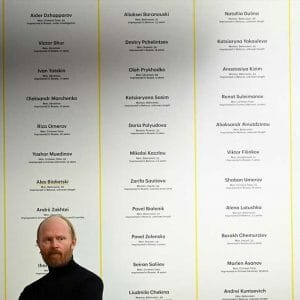

An activist in Colombia, the deadliest country in the world for human rights defenders in 2022, accounting for 186 killings – or 46% – of the global total registered last year. Credit: Sebastian Barros

By Bibbi Abruzzini and Clarisse Sih, Forus

BRUSSELS, Apr 27 2023 (IPS)

In today’s world, human rights defenders face immense challenges, with threats, attacks, and repression being rampant in many countries. According to the latest report by Front Line Defenders, killings of rights defenders increased in 2022, with a total of 401 deaths across 26 different countries. Despite the adoption of the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders 25 years ago, the threats faced by defenders persist globally.

One striking example of the dire situation is in Bolivia, where violations of freedoms of expression, association, peaceful assembly, and the right to defend rights have been recorded by the Observatory of Rights Defenders of UNITAS, with the Permanent Assembly of Human Rights of Bolivia (APDHB) being a longstanding victim of attacks and delegitimization. A total of 725 violations of the freedoms of expression, association and peaceful assembly, democratic institutions and the right to defend rights have been recorded by the Observatory of Rights Defenders.

Gladys Sandova, a human rights and environmental defender in the Tariquía Flora and Fauna National Reserve in Bolivia, reveals how the state often aligns with oil businesses instead of protecting communities. “Tariquía is the lung of Tarija,” Gladys explains, yet this vital source of water for southern Bolivia and home to over 3,000 people, is at risk due to the state-owned Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales Bolivianos (YPFB) seeking to revive oil exploration in the reserve.

“Oil companies are here, we are going to lose our natural richness, they are going to affect the lives of families, and contaminate our water and our air,” says Gladys, reflecting the urgent need to defend human rights and the environment.

Her story is similar to that of several other human rights defenders across the globe : they are victims of hostilities, interference, threats, and harassment. The campaign, ReImagina La Defensa de Derechos, by UNITAS collects the testimonies of human rights defenders and indigenous leaders across Bolivia raising awareness about the challenges they face.

Stories from human rights defenders from across the globe are also featured in the #AlternativeNarratives campaign, which seeks to amplify the voices of civil society organizations and grassroots movements that work towards social justice, human rights, and sustainable development. The campaign encourages the use of storytelling, multimedia tools, and creative expression to highlight alternative perspectives, challenge stereotypes, and advocate for positive chang while fostering a more inclusive and equitable narrative space that reflects the diversity of human experiences and promotes solidarity, empathy, and mutual understanding.

Human rights defenders, including women defenders, continue to mobilize against repressive regimes and occupying forces in countries like Afghanistan, the DRC, El Salvador, Iran, Myanmar, Sudan, and Ukraine. Mary Lawlor, UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, highlights the underreporting of human rights violations against defenders, particularly women, and outlines “disturbing trends” in relation to civic space worldwide.

Repongac, representing over 1,200 NGOs in Central Africa, states that “human rights in Central Africa are no longer guaranteed,” with civil society actors, journalists, and defenders facing repression, prosecution, and arrests. Recent campaigns organized by Repongac in Central Africa and Repaoc in West Africa, supported by Forus and the French Development Agency, brought together diverse stakeholders, including human rights defenders, political parties, parliamentarians, journalists, and security personnel, to initiate a dialogue and protect civic space amnd fundametnal freedoms in the region.

To support activists and defenders globally, the Danish Institute for Human Rights has launched a monitoring tool that assesses whether an enabling environment for human rights defenders exists across five critical areas. Developed in collaboration with 24 institutions and organizations, including the United Nations and civil society networks, the tool not only tracks the number of killings of human rights defenders but also analyzes the presence of appropriate legislation and practices to protect defenders.

As Carol Rask, a representative of the Danish Institute for Human Rights, explains, defending human rights is a crime in some countries and a deadly activity in others. It is a call to action for change, urging individuals, organizations, and governments to prioritize and protect the crucial work of human rights defenders worldwide.

Griselda Sillerico, human rights defender in Bolivia for over 30 years, quotes Ana María Romero and says “human rights are seeds that we continue to plant and that over the years we harvest.” Griselda Sillerico’s quote echoes the enduring spirit of human rights advocacy, where the work of human rights defenders like her is a constant effort to sow the seeds of justice, equality, and dignity for all. Despite the challenges and setbacks, human rights defenders across the world continue to plant these seeds, often at great personal risk, with the hope of reaping a future where human rights are universally respected and protected.

IPS UN Bureau