Africa, Biodiversity, Conferences, Development & Aid, Editors’ Choice, Environment, Featured, Global, Headlines, Health, Sustainability, Sustainable Development Goals, TerraViva United Nations

More than 1,400 delegates are present at two crucial meetings, where the topic of preserving the planet’s ongoing biodiversity for the benefit of humanity is under discussion. Under the spotlight are the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, synthetic biology, the detection and identification of living modified organisms, and, critically, biodiversity and health.

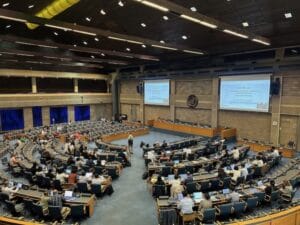

Over 1,400 delegates, including 600 representing parties or signatories from over 150 countries and a significant delegation of Indigenous Peoples and other observer organizations, including women’s groups are attending two crucial biodiversity meetings in Nairobi, Kenya. Credit: Stella Paul/IPS

– The 26th meeting of the Subsidiary Body of Scientific, Technical, and Technological Advisors (SBSTTA) of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (UNCBD) started in Nairobi, Kenya, on Monday. Over 1,400 delegates, including 600 representing signatories or parties from over 150 countries, are present for the seven-day meeting at the headquarters of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). A large number of members from Indigenous Peoples and other observer organizations, including women’s groups, are also attending the meetings.

SBSTTA will be followed by the meeting of the Subsidiary Body on Implementation (SBI), another subsidiary body of the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The SBI will take place from May 20–29 at the same venue.

Opening the meeting on Monday morning, David Cooper, the Acting Executive Secretary of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity, called on the delegates for a successful meeting.

“A key part of ensuring the implementation of the Global Biodiversity Framework is to monitor the progress and that’s why finalizing a monitoring framework includes authenticators for the parties to report on. I would like to give my sincere appreciation to all those working on putting together a comprehensive set of authenticators. I encourage you to make full use of what we have achieved so far and let’s make this meeting a success,” Cooper said.

IPS, which is exclusively covering the meetings, has insights into the meetings and presents here the brief history of both the meetings and their significance in larger global biodiversity protection, especially in the global south, including the implementation of the Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), the legally binding international biodiversity treaty adopted by the nations in December 2022

SBSTTA: History, Mandate and Role in the COP

SBSTTA was established 30 years ago, in 1994, as a subsidiary body of the CBD during the first meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP) to the CBD in Nassau, Bahamas. Article 25 of the CBD, which mandated its creation, tasked it with giving the COP timely advice regarding the application of the Convention.

Since then, SBSTTA ‘s main role has been providing assessments of scientific, technical, and technological information relevant to the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity. It typically meets once or twice a year to review and assess relevant scientific information, including reports submitted by Parties, relevant organizations, and stakeholders. Its discussions cover a wide range of topics, including biodiversity loss, ecosystem services, invasive species, genetic resources, and biotechnology.

The main output of SBSTTA meetings is a set of recommendations to the COP, which are based on the scientific and technical assessments conducted during its sessions. These recommendations provide guidance to Parties and other stakeholders on key issues related to the implementation of the CBD.

For example, in 2007, SBSTTA recommended that the biodiversity COP consider the potential impacts of synthetic biology on biodiversity and ecosystems and encourage Parties to undertake further research, risk assessments, and regulatory measures to address any potential risks associated with the release of synthetic organisms into the environment.

This recommendation was later taken up by the CBD COP, leading to the adoption of decisions on synthetic biology, including Decision XIII/17, which encouraged Parties to continue their efforts to address the potential positive and negative impacts of synthetic biology on biodiversity, and take a precautionary approach.

A more recent example is the SBSTTA’s recommendation from 2018 that the COP should encourage Parties to mainstream biodiversity considerations into sectoral and cross-sectoral policies, plans, and programs, including those pertaining to agriculture, fisheries, forestry, tourism, energy, and infrastructure.

The CBD COP later agreed with this suggestion, which led to the adoption of decisions and guidelines on mainstreaming biodiversity across sectors. One of these was Decision XIV/4, which asked Parties to do more to mainstream biodiversity into relevant sectors and to encourage synergies between the goals of sustainable development and biodiversity conservation.

SBSTTA and Genetically Modified Mosquitoes

SBSTTA-26 has a large number of issues on its agenda. Most prominent among them are: 1) creating a monitoring framework for the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework; 2) synthetic biology; 3) detection and identification of living modified organisms; and 4) biodiversity and health.

It is expected that under the detection and identification of living modified organisms, genetically engineered mosquitoes for Malaria prevention will be discussed. Research on genetically engineered mosquitoes for malaria control has been an area of interest and investigation for several years, although little information is available on it in the public domain.

Scientists in many countries, including in the United States and Brazil, have been exploring various genetic modification techniques to create mosquitoes that are resistant to the malaria parasite or are unable to transmit the disease. One approach involves genetically modifying mosquitoes to produce antibodies that neutralize the malaria parasite when it enters their bodies.

The other approach is to use “Gene Drive Technology,” which involves modifying mosquitoes in a way that ensures the modified genes are passed on to a high proportion of their offspring. Already, many field trials of genetically engineered mosquitoes have been conducted or are underway in different parts of the world, most notably those conducted by the company Oxitec in Brazil and the Cayman Islands.

At the SBSTTA, scientific and technical advisors will look closely at the important environmental and ethical considerations related to GE mosquitoes. According to the World Health Organization’s 2023 World Malaria Report, there has been an increase in malaria infections all over the world as a result of climate change. However, several countries and organizations have serious reservations against the release of GM mosquitoes, which they believe may have an irreversible and devastating impact on local biodiversity. One of the most vocal organizations against GE/GM mosquitoes has been Friends of the Earth, a US-based environmental advocacy group. Dana Perls, senior program manager at Friends of the Earth, said, “Significant scientific research on genetically engineered mosquitoes is still needed to understand the potential public health and environmental threats associated with the release of this novel genetically engineered insect.”

The SBSTTA is expected to witness passionate discussions, especially from environmental NGOs and faith-based organizations, including the need to ensure that communities are properly informed and engaged in decision-making processes, especially in the global south.

The agenda for the meetings includes creating a monitoring framework for the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, synthetic biology, detection and identification of living modified organisms, and biodiversity and health. Credit: Stella Paul/IPS

SBI: Most Crucial Agenda Items

The SBI was established under the CBD during the third meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP) to the CBD in 1996. The SBI’s mandate includes providing guidance and recommendations to the COP on matters related to the implementation of the CBD as well as identifying obstacles and challenges that may hinder effective implementation.

Like SBSTTA, SBI also typically meets once or twice a year to conduct its work. Its discussions cover a wide range of topics related to the implementation of the CBD, including national biodiversity strategies and action plans, financial resources and mechanisms, capacity-building, and technology transfer.

Chaired by Chirra Achalender Reddy of India, the SBI in Nairobi has placed several items on its agenda. However, the most crucial ones among them are: 1) resource mobilization and financial mechanisms; 2) a review of the progress in national target setting; and 3) the updating of national biodiversity strategies and action plans.

As IPS recently reported, only a handful of countries have so far been able to submit their updated biodiversity action plans, while the rest are said to be facing multiple challenges in doing so, including a lack of capacity. In fact, Kenya, the host country of these meetings, has not been able to submit their updated action plan yet.

On Monday, in her inaugural address during the opening ceremony of SBSTTA, Ingrid Andersen, the Executive Director of UNEP, acknowledged that a lack of capacity to revise and update their action plans has been reported by several member states. “Capacity building is a serious issue and at the SBSTTA and SBI, this will be seriously discussed,” Andersen said.

David Ainsworth, the Communications Director of UNCBD, said that the capacity is lacking in several areas, including communications (where countries do not know how to communicate to different ministries the need for working together to develop their biodiversity action plans), finance (lack of funding, budgetary constraints), and knowledge.

“Perhaps the most crucial of these is finance and this will be seriously discussed at the SBI,” Ainsworth said.

IPS UN Bureau Report

This is only the beginning of our journey to create a great momentum of youth standing up for a better future. As a next step to amplify youth voices, we plan to communicate with MOFA, a focal point of the Summit of the Future. We, the organizing committee, will also participate in the UN Civil Society Conference that will take place in Nairobi, Kenya in May, which is a key milestone for civil society to give their input to the Member States. We hope to convey the survey results to the co-chairs and UN high-level officials during the conference. In addition, at a national level, we will engage with the government, the UN, and like-minded organizations to contribute to the Pact for the Future in a meaningful way.

This is only the beginning of our journey to create a great momentum of youth standing up for a better future. As a next step to amplify youth voices, we plan to communicate with MOFA, a focal point of the Summit of the Future. We, the organizing committee, will also participate in the UN Civil Society Conference that will take place in Nairobi, Kenya in May, which is a key milestone for civil society to give their input to the Member States. We hope to convey the survey results to the co-chairs and UN high-level officials during the conference. In addition, at a national level, we will engage with the government, the UN, and like-minded organizations to contribute to the Pact for the Future in a meaningful way.