Civil Society, Climate Change, Crime & Justice, Featured, Gender Violence, Headlines, Human Rights, Latin America & the Caribbean, Migration & Refugees, TerraViva United Nations

Credit: David Peinado/Anadolu via Getty Images

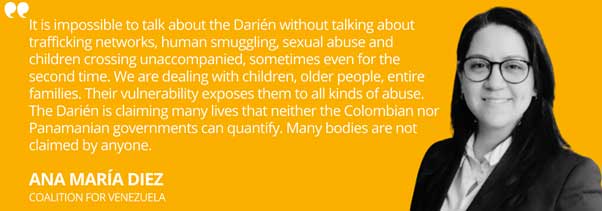

– The Darién Gap is a stretch of jungle spanning the border between Colombia and Panama, the only missing section of the Pan-American Highway that stretches from Alaska to southern Argentina. For good reason, it used to be considered impenetrable. But in 2023, a record 520,000 people crossed it heading northwards, including many children. Many have lost their lives trying to cross it.

People are also increasingly taking to the seas. A new people trafficking route has opened up across the Caribbean Sea via the Bahamas. Growing numbers of desperate migrants – mostly from conflict-ridden Haiti but also from more distant countries – are using it in an attempt to reach Florida. It’s risky too. In November 2023, at least 30 people died when a boat from Haiti capsized off the Bahamas.

The pattern is clear: as is also the case in Europe, when safer routes are closed off, people start taking riskier ones. Millions of people in Latin American and Caribbean countries are fleeing authoritarianism, insecurity, violence, poverty and climate disasters. Most remain in other countries in the region that typically present fewer challenges to arriving migrants – but also offer limited opportunities. The USA therefore remains a strong migration magnet. Its tightening immigration policies are the key reason people are heading into the jungle and taking to the sea.

Dynamic trends

Out of the staggering 7.7 million Venezuelans who’ve left their country since 2017 – greater than the numbers of displaced Syrians or Ukrainians – almost three million have stayed next door in Colombia, with about 1.5 million in Peru, close to half million in both Brazil and Ecuador, and hundreds of thousands in other countries across the region.

Latin American host countries are relatively welcoming. Unlike in many global north countries, politicians don’t usually stoke xenophobia or vilify migrants for political gain, and states don’t usually reject people at borders or deport them, and instead try to provide paths for legal residence. Overall they’ve been pragmatic enough to strike a balance between openness and orderly entry. As a result, a high proportion of Venezuelan migrants have acquired some form of legal status in host countries.

But host states haven’t planned for long-term integration. They face typical global south challenges, such as high levels of inequality and many unmet social needs. That’s why those moving towards the USA include many Haitians, Nicaraguans and Venezuelans who were already living in other countries. They are mostly driven by the lack of opportunities, although in the case of Haitians language barriers and racial discrimination are also significant motivators.

While the USA has tightened its migration policies, its porous southern border – the longest border between global north and global south – remains inviting for many. In its 2022 fiscal year, US authorities had a record 2.4 million encounters with unauthorised migrants at the border. Many had come a long way, having crossed the Darién Gap and then headed across Central America and Mexico.

Dangerous journeys

People do so at great risk. According to the United Nations’ Missing Migrants Project reported at least 1,275 people died or went missing during migration in the Americas in 2023.

It’s unclear how many people have perished so far in the Darién Gap. In many cases, deaths go unreported and bodies are never recovered. The crossing can take anywhere from three to 15 days. As they cross rivers and mountains, people suffer from the jungle’s harshness and difficult weather.

According to Doctors Without Borders (MSF), much of the danger is because the Darién is one of the world’s most humid regions and doesn’t have any proper infrastructure. People can easily slip and fall on its steep paths or drown in rushing rivers. Hired guides can leave people stranded. Those who can’t keep up can get disoriented and lost. The difficult terrain forces many to leave their supplies along the way, including food and drinking water.

Migrants also often cross paths with local criminal groups that steal from them, kidnap them or commit rape. In December 2023, MSF recorded a seven-fold increase in monthly incidents of sexual violence. But despite the dangers, the number of people crossing in 2023 almost doubled compared to 2022.

The Darién Gap is only the gateway to Central America – the start of a much longer journey. The dangers don’t stop. Many end up staying somewhere in Mexico, but others keep marching northwards and face many hazards trying to reach the USA – drowning , or dying of heat exposure and dehydration in the desert during the day, or of hypothermia at night. Migrants have also died of asphyxiation in botched migrant smuggling operations. They are often blackmailed by smugglers and experience human rights abuses, including lethal violence, from Border Patrol agents.

US policies

Starting in early 2021, the administration of President Joe Biden made several changes to US immigration policies, such as rescinding the travel ban on primarily Muslim-majority and African countries, restoring the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals programme and granting Venezuelans living in the USA Temporary Protection Status, among other things.

But it was only in May 2023 that the Biden administration finally lifted Title 42, a public health order that, under the cover of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Trump administration used to immediately expel those caught crossing the border, with no right to apply for asylum. At the same time, however, the government issued several new rules that became known as the ‘asylum ban’. Before showing up at the border, people are now required to make an appointment with a smartphone app or have proof they have previously sought and failed to obtain asylum in the countries they’ve travelled through on their way to the USA. If they don’t comply with these requirements, they’re automatically presumed ineligible for asylum and can be subjected to expedited removal.

Civil society points out that it’s very difficult to get an appointment. The app frequently fails and many migrants don’t have smartphones, adequate wi-fi or a data plan. They face language and education barriers and are exploited by people pretending to help. Barriers to seeking asylum have risen to the point that advocates view them as violating the Refugee Convention’s principle of non-refoulment, according to which people can’t be returned to a country where they face serious threats to their life or freedom.

Election politics

Pressure is intensifying as the USA’s November 2024 presidential election approaches.

Republican governors of southern states such as Texas have made a show of bussing newly arrived migrants to far-off cities run by Democrats, dumping them there with no support, treating them as pawns in a political game. Congress Republicans have also repeatedly delayed backing support to Ukraine unless new border control measures are enacted in return.

In October 2023, Biden announced plans to strengthen the southern border and resume deportation flights to Venezuela, which had been paused. But no one has gone lower than Donald Trump, who recently told a rally that ‘immigrants are poisoning the blood of our country’ – a straightforward use of white supremacist rhetoric. His comments have grown increasingly dehumanising – he has repeatedly referred to migrants as ‘animals’.

In his 2023 State of the Union speech, President Biden responded to Trump directly, stating he refused to ‘demonise immigrants’. But in the same breath he urged Republicans to pass a bipartisan immigration bill they’re currently blocking, which would further tighten asylum rules, expand funding for border operations and give the president authority to empower border officials to summarily deport migrants during spikes in illegal immigration. The bill continues to be rejected by hardcore Republicans who see it as not strict enough.

For migrants and asylum seekers, the prospects look bleak. As far as their rights are concerned, the election campaign is a race to the bottom. A Trump victory could only bring further bad news – but a Biden win is unlikely to promise much progress. Election results aside, people will keep taking to the sea or venturing through the jungle, the barbed wire and the desert. Politicians need to recognise this reality and commit to upholding the human rights of all who strive to find a future in the USA.

Inés M. Pousadela is CIVICUS Senior Research Specialist, co-director and writer for CIVICUS Lens and co-author of the State of Civil Society Report.