Asia-Pacific, Civil Society, Development & Aid, Education, Headlines, Poverty & SDGs, Regional Categories, TerraViva United Nations

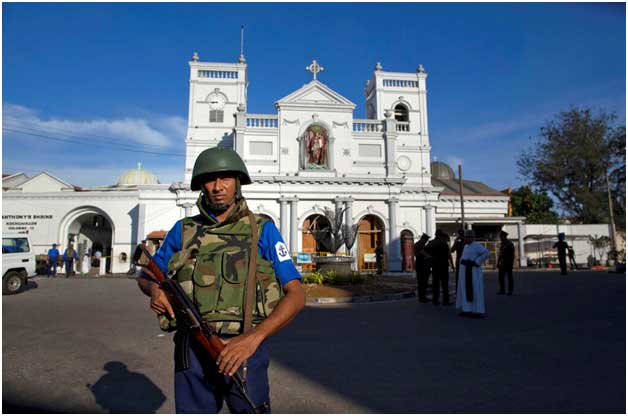

Photo Courtesy: Sachin Sachdeva

– Communities are treated as passive recipients, giving them no say in the functioning of their schools. Here’s why this needs to change.

During our work with people living around the Ranthambhor National Park on issues of conservation, livelihoods, and eco-development, a constant question we were asked was how long we thought we could continue helping them. And then, an accompanying question — would their children never be in a position to help themselves? To advocate for and implement the change they wanted to see?

People had been led to believe that sending children to school was a precondition for a better future. Despite this, what they kept seeing was that the education system accessible to them was not equipping their children with the skills and abilities that they required to negotiate better futures for themselves.

Poor solutions for poor people

Working in Sawai Madhopur made us painfully aware of the community’s past experiences with education. Over time they had experienced the Shiksha Karmi Programme (which trained daughters-in-law to run schools), and the Rajiv Gandhi Pathshalas (which trained a young person who had passed Class 10, to run schools), not counting their countless experiences with government schools in the larger villages, most of which were sub-optimal.

When we look at the pitfalls of the government schooling system — be it teacher absenteeism, quality of textbooks, a lack of adequate infrastructure, constrained budgets and human resources — and the plans or schemes that have been created to address them, we realise that most of them could be categorised as ‘poor solutions for poor people’.

The current school system has made communities passive recipients of whatever the government tosses at them, giving them no say in the functioning of the school. It does not work with the community to help them actively engage with the process.

People don’t understand the gap between their aspirations and reality

The idea that any kind of education should lead to a job (preferably a government one) is prevalent amongst the communities we work with. However, what is less clear is how exactly that will happen, and what the probability is of it happening at all.

People had begun to realise that their education system was leaving children under prepared – they may have completed class 10 or 12, but their capacities and skill sets were far lower than they should have been – making it impossible for them to find the job they dreamed of, or continue on an educational path that would get them there.

What’s worse, by dedicating most of their time and resources to school, these children were sometimes unable to take up their traditional occupations – be it in agriculture or livestock rearing – making them incapable of earning a substantial income.

In such a situation, with huge gaps between their reality and aspirations, young people often found themselves helpless. There was scarcely anyone in the village who could have told them what needed to be done to become a doctor, engineer, bureaucrat, lawyer, entrepreneur – or what it entailed.

Despite this, children would go through their schools and come to urban centres looking for opportunities – be it that elusive government job or being a professional. It was only upon reaching the cities that they would realise how under-prepared they were, and as a result end up taking whatever work they could get–as waiters, drivers, cleaners, helpers, construction workers and similar positions in the informal sector.

It is no surprise then, that when it came to education, people in the community were losing faith in government schools.

Communities are the main stakeholder in their education

People often believe that the problems in the education space have more to do with curricula or pedagogy, or with the capacity of teachers. We disagree. The main issue is that today, communities are missing from the school ecosystem.

The community is the biggest stakeholder in the education space, and they need to be treated as such. People need to have a real idea of what they can expect from the system, and they need the system to be accountable to them. This has never happened.

So while there is plenty of work being done to train teachers, help principals, build the skills of School Management Committees (SMCs), design curriculum and change pedagogy, there is not enough being done with parents and community members. Even though parents make up the bulk of the SMC, they tend to be involved only in issues related to infrastructure or for instance, looking at teacher attendance or organising events – essentially any activity that is easy to monitor and does not demand engagement in processes.

It is time that we understood that education is about creating the right ecosystem for learning to happen, and that a village and its community are part of that process. When families have a better understanding of learning processes, they will also ensure that the home environment provides the right encouragement. When community members are able to offer their knowledge—as farmers, mechanics or officers in government—to students, they are teaching children about different possibilities in their future. It is only through involvement of the community that people will learn to ask the right questions, to seek accountability from the system. SMCs, being a subset of the community, offer a channel to do this. And if the community is aware, the SMCs will also function well.

For change to occur, communities must be more aware, and in charge of their education.

Photo Courtesy: Sachin Sachdeva

Working with communities to improve the education system

Having said that, we have to keep in mind that today, most communities, having been passive recipients of education thus far, are unprepared to challenge the system. It is therefore essential that we work to change this.

Based on our work at Gramin Shiksha Kendra (GSK) – an organisation which works with communities to enhance the quality of education in government schools – over the last 14 years, here are some suggestions on how this can be done:

1. Give them positions of seniority/power

Include members of the local community in your organisation board and involve them in the decision making. For example, at GSK we have people from the community on our board – some of them are parents who missed the opportunities of a quality education for their children, and two of them have never been to school but bring in their insights, wisdom and understanding of the local context.

These community members have guided and helped the organisation evolve its strategies, brought concerns and aspirations of the people to the board, and cautioned us against taking decisions that might not have the right impact.

2. Change your metrics of success

For example, we have kept the strength and management capacities of the school management committees as our apex indicator of success/failure, rather than only focussing on learning outcomes. We believe that when the schools and government-appointed school teachers become accountable to the SMC, and the SMC is in a position to guide and manage, the initiative will have succeeded.

3. Involve them in the work being done

Members from the community are invited to teach in the schools as guest teachers. Their experiences add to the curriculum of the school and are adapted for the schools. To be a teacher is still a valued profession, which gives parents a sense of importance and respect in the area.

Additionally, in an attempt to create a community-led ecosystem for education, we have an annual education festival called Kilol in our villages. The village community takes responsibility to organise Kilol’s and GSK shares, through exhibits and processes, our ways of teaching science, language, math, as well as the importance of components like pottery, sport and carpentry. The festival gives everyone in the community an opportunity to celebrate learning and understand what happens in school.

4. Give the initiative that is for them, to them

Our latest attempt is in handing over one of the schools that GSK set up back to the community to manage. That is when the school will become truly community-owned and community-managed.

We made this possible by, over the last 14 years, giving different members from the community a chance to be a part of the SMC. This has resulted in over 35 members in the community who have at one point or another been members of the SMC.

Because of their experience, the SMCs will soon be able to take over the management of the school and run it. GSK plans to facilitate this process and will help the SMC and the community evolve a future course of action – whether that leads to a science education initiative in the area, a comprehensive school, or an outreach programme.

This is important, as it defines our education initiative in the area. We don’t intend running the schools for ever, we want the community to take over. This will be our biggest success and we will continue providing them the technical support – or any other support that they may require. Most importantly, by giving the school back to the community, we are giving power back to the people – which is where it should be.

Sachin Sachdeva is a Co-Founder of Gramin Shiksha Kendra, www.graminshiksha.org.in , an organisation which works with communities to enhance the quality of education in government schools. Sachin has worked with development initiatives over the past 25 years and has been working with communities to help them look at their futures from a position of strength. GSK works with over 70 schools around the Ranthambhor National Park and along with the community runs three schools, one of which has been set up in a rehabilitated village. He is currently Director of the Paul Hamlyn Foundation’s India programme.

This story was originally published by India Development Review (IDR)