Civil Society, Development & Aid, Economy & Trade, Global, Headlines, IPS UN: Inside the Glasshouse, TerraViva United Nations, Trade & Investment

– International governance arrangements are in trouble. Condemned as ‘dysfunctional’ by some, multilateral agreements have been discarded or ignored by the powerful except when useful to protect their interests or provide legitimacy.

Economic multilateralism under siege

Undoubtedly, many multilateral arrangements have become less appropriate. At their heart is the United Nations (UN) system, conceived in the last year of US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s presidency and World War Two.

Jomo Kwame Sundaram

The 1944 UN conference at Bretton Woods sought to build the foundations for the post-war economic order. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) would create conditions for lasting growth and stability, with the World Bank financing post-war reconstruction and post-colonial development.

The Bretton Woods agreement allowed the US Federal Reserve Bank (Fed) to issue dollars, as if backed by gold. In 1971, President Richard Nixon repudiated the US’s Bretton Woods obligations. With US military and ‘soft’ power, widespread acceptance of the dollar since has effectively extended the Fed’s ‘exorbitant privilege’.

This unilateral repudiation of US commitments has been a precursor of the fate of some other multilateral arrangements. Most were US-designed, some in consultation with allies. Most key privileges of the global North – especially the US – continue, while duties and obligations are ignored if deemed inconvenient.

The International Trade Organization (ITO) was to be the third leg of the post-war multilateral economic order, later reaffirmed by the 1948 Havana Charter. Despite post-war world hegemony, the ITO was rejected by the protectionist US Congress.

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) became the compromise substitute. Recognizing the diversity of national economic capacities and capabilities, GATT did not impose a ‘one-size-fits-all’ requirement on all participants.

But lessons from such successful flexible precedents were ignored in creating the World Trade Organization (WTO) from 1995. The WTO has imposed onerous new obligations such as the all-or-nothing ‘single commitment’ requirement and the Agreement on Trade-related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

Overcoming marginalization

In September 2021, the UN Secretary-General (SG) issued Our Common Agenda, with new international governance proposals. Besides its new status quo bias, the proposals fall short of what is needed in terms of both scope and ambition.

Problematically, it legitimizes and seeks to consolidate already diffuse institutional responsibilities, further weakening UN inter-governmental leadership. This would legitimize international governance infiltration by multi-stakeholder partnerships run by private business interests.

The last six decades have seen often glacially slow changes to improve UN-led gradual – mainly due to the recalcitrance of the privileged and powerful. These have changed Member State and civil society participation, with mixed effects.

Fairer institutions and arrangements – agreed to after inclusive inter-governmental negotiations – have been replaced by multi-stakeholder processes. These are typically not accountable to Member States, let alone their publics.

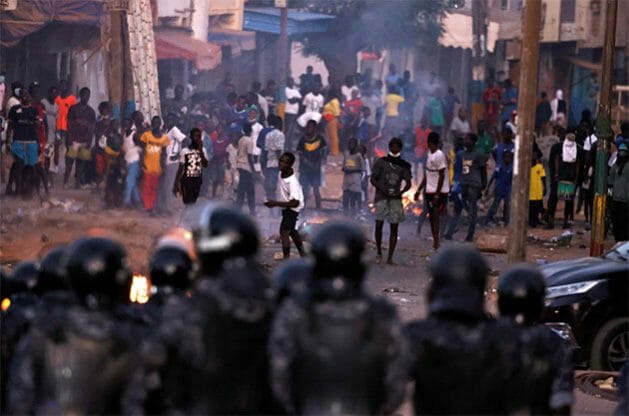

Such biases and other problems of ostensibly multilateral processes and practices have eroded public trust and confidence in multilateralism, especially the UN system.

Multi-stakeholder processes – involving transnational corporate interests – may expedite decision-making, even implementation. But the most authoritative study so far found little evidence of net improvements, especially for the already marginalized.

New multi-stakeholder governance – without meaningful prior approval by relevant inter-governmental bodies – undoubtedly strengthens executive authority and autonomy. But such initiatives have also undermined legitimacy and public trust, with few net gains.

All too often, new multi-stakeholder arrangements with private parties have been made without Member State approval, even if retrospectively due to exigencies.

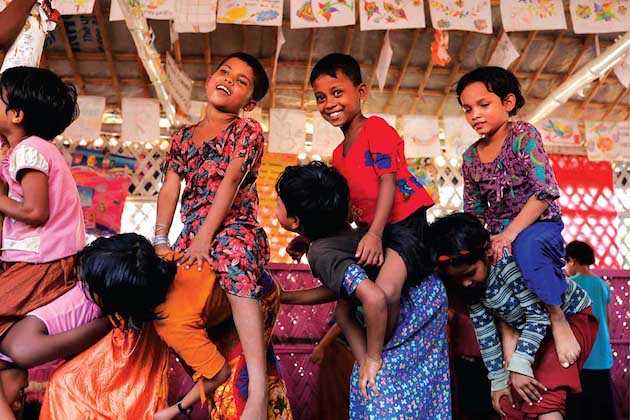

Unsurprisingly, many in developing countries have become alienated from and suspicious of those acting in the name of multilateral institutions and processes.

Hence, many in the global South have been disinclined to cooperate with the SG’s efforts to resuscitate, reinvent and repurpose undoubtedly defunct inter-governmental institutions and processes.

Way forward?

But the SG report has also made some important proposals deserving careful consideration. It is correct in recognizing the long overdue need to reform existing governance arrangements to adapt the multilateral system to current and future needs and requirements.

This reform opportunity is now at risk due to the lack of Member State support, participation and legitimacy. Inclusive consultative processes – involving state and non-state actors – must strive for broadly acceptable pragmatic solutions. These should be adopted and implemented via inter-governmental processes.

Undoubtedly, multilateralism and the UN system have experienced growing marginalization after the first Cold War ended. The UN has been slowly, but surely superseded by NATO and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), led by the G7 group of the biggest rich economies.

The UN’s second SG, Dag Hammarskjold – who had worked for the OECD’s predecessor – warned the international community, especially developing countries, of the dangers posed by the rich nations’ club. This became evident when the rich blocked and pre-empted the UN from leading on international tax cooperation.

Seeking quick fixes, ‘clever’ advisers or consultants may have persuaded the SG to embrace corporate-dominated multi-stakeholder partnerships contravening UN norms. More recent SG initiatives may suggest his frustration with the failure of that approach.

After the problematic and controversial record of such processes and events in recent years, the SG can still rise to contemporary challenges and strengthen multilateralism by changing course. By restoring the effectiveness and legitimacy of multilateralism, the UN will not only be fit, but also essential for humanity’s future.

IPS UN Bureau