Active Citizens, Biodiversity, Civil Society, Climate Action, Conservation, Crime & Justice, Editors’ Choice, Environment, Featured, Gender, Headlines, Human Rights, Latin America & the Caribbean, Regional Categories, TerraViva United Nations, Water & Sanitation, Women & Climate Change

Dozens of women environmentalists participated in Mexico City in the launch of the Voices of Life campaign by eight non-governmental organizations on Oct. 12, 2023, which brings together hundreds of activists in five of the country’s 32 states. CREDIT: Emilio Godoy / IPS

– The defense of the right to water led Gema Pacheco to become involved in environmental struggles in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, an area threatened by drought, land degradation, megaprojects, mining and deforestation.

Care “means first and foremost to value the place where we live, that the environment in which we grow up is part of our life and on which our existence depends,” said Pacheco, deputy municipal agent of San Matías Chilazoa, in the municipality of Ejutla de Crespo, some 355 kilometers south of Mexico City.

“We are in the phase of seeing how the Escazú Agreement will be applied. The most important thing is effective implementation. It is something new and it will not be ready overnight.” — Gisselle García

A biologist by profession, the activist is a member of the Local Committee for the Care and Defense of Water in San Matías Chilazoa, which belongs to the Coordinating Committee of Peoples United for the Care and Defense of Water (Copuda).

The local population is dedicated to growing corn, beans and chickpeas, an activity hampered by the scarcity of water in a country that has been suffering from a severe drought over the past year.

To deal with the phenomenon, the community created three water reservoirs and infiltration wells to feed the water table.

“Women’s participation has been restricted, there are few women in leadership positions. The main challenge is acceptance. There is little participation, because they see it as a waste of time and it is very demanding,” lamented Pacheco.

In November 2021, the 16 communities of Copuda obtained the right to manage the water resources in their territories, thus receiving water concessions.

But women activists like Pacheco face multiple threats for protecting their livelihoods and culture in a country where such activities can pose a lethal risk.

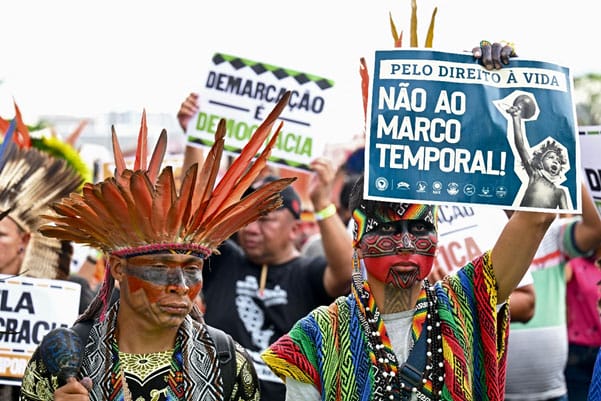

For this reason, eight organizations from five Mexican states launched the Voices of Life campaign on Oct. 12, involving hundreds of habitat protectors, some of whom came to the Mexican capital for the event, where IPS interviewed several of them.

Involvement in the defense of water led Gema Pacheco to become an environmental activist, participating in the Voices of Life campaign in Mexico, which seeks to bring visibility and respect to this high-risk activity in Mexico. CREDIT: Emilio Godoy / IPS

The initiative seeks to promote the right to a healthy environment, facilitate environmental information, protect and recognize people and organizations that defend the environment, as well as learn how to use information and communication technologies.

In 2022, Mexico ranked number three in Latin America in terms of murders of environmental activists, with 31 killed (four women and 16 indigenous people), behind Colombia (60) and Brazil (34), out of a global total of 177, according to the London-based non-governmental organization Global Witness.

A year earlier, this Latin American country of almost 129 million inhabitants ranked first on the planet, with 54 killings, so 2022 reflected an improvement.

“The situation in Mexico remains dire for defenders, and non-fatal attacks, including intimidation, threats, forced displacement, harassment and criminalization, continued to greatly complicate their work,” the report says.

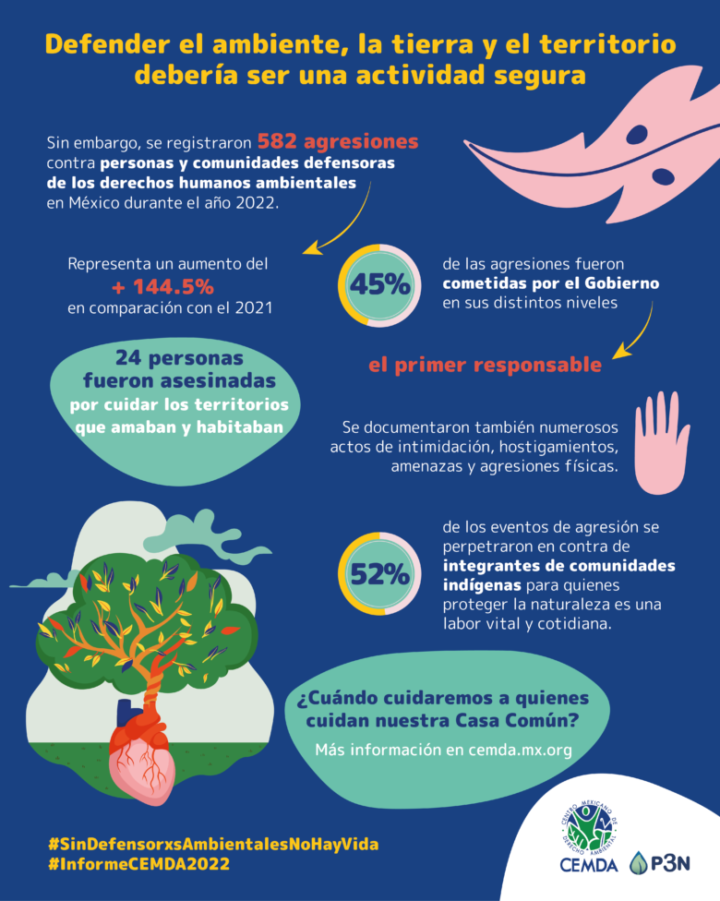

The outlook remains serious for activists, as the non-governmental Mexican Center for Environmental Law (Cemda) documented 582 attacks in 2022, more than double the number in 2021. Oaxaca, Mexico City and the northern state of Chihuahua reported the highest number of attacks.

Urban problems

The south of Mexico City is home to the largest area of conservation land, but faces growing threats, such as deforestation, urbanization and irregular settlements.

Protected land defines the areas preserved by the public administration to ensure the survival of the land and its biodiversity.

Social anthropologist Tania Lopez said another risk has now emerged, in the form of the new General Land Use Planning Program 2020-2035 for the Mexican capital, which has a population of more than eight million people, although Greater Mexico City is home to more than 20 million.

“There was no public consultation of the plan based on a vision of development from the perspective of native peoples. In addition, it encourages real estate speculation, changes in land use and invasions,” said López, a member of the non-governmental organization Sembradoras Xochimilpas, part of the Voices of Life campaign.

Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries in the world for environmental defenders. In 2022, 31 activists were murdered, the third highest number in the region behind Colombia and Brazil. CREDIT: Cemda

Apart from the failure to carry out mandatory consultation processes, activists point out irregularities in the governmental Planning Institute and its technical and citizen advisory councils, because they are not included as members.

The conservation land, which provides clean air, water, agricultural production and protection of flora and fauna, totals some 87,000 hectares, more than half of Mexico City.

The plan stipulates conservation of rural and urban land. But critics of the program point out that the former would lose some 30,000 hectares, destined for rural housing.

The capital’s legislature is debating the program, which should have been ready by 2020.

Gisselle García, a lawyer with the non-governmental Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense, said attacks on women activists occur within a patriarchal culture that limits the existence of safe spaces for women’s participation in the defense of rights.

“It’s an entire system, which reflects the legal structure. If a woman files a civil or criminal complaint, she is not heard,” she told IPS, describing the special gender-based handicaps faced by women environmental defenders.

Social anthropologist Tania López is one of the members of the Voices of Life campaign, launched by eight non-governmental organizations on Oct. 12, 2023 to highlight the work of women environmental defenders in Mexico. CREDIT: Emilio Godoy / IPS

Still just an empty promise

This risky situation comes in the midst of preparations for the implementation of the Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, known as the Escazú Agreement, an unprecedented treaty that aims to mitigate threats to defenders of the environment, in force since April 2021.

Article 9 of the Agreement stipulates the obligation to ensure a safe and enabling environment for the exercise of environmental defense, to take protective or preventive measures prior to an attack, and to take response actions.

The treaty, which takes its name from the Costa Rican city where it was signed, guarantees access to environmental information and justice, as well as public participation in environmental decision-making, to protect activists.

The Escazú Agreement has so far been signed by 24 Latin American and Caribbean countries, 15 of which have ratified it as well.

But its implementation is proceeding at the same slow pace as environmental protection in countries such as Mexico, where there are still no legislative changes to ensure its enforcement.

In August, the seven-person Committee to Support the Implementation of and Compliance with the Escazú Agreement took office. This is a non-contentious, consultative subsidiary body of the Conference of the Parties to the agreement to promote and support its implementation.

Meanwhile, in Mexico, the Escazú National Group, made up of government and civil society representatives, was formed in June to implement the treaty.

During the annual regional Second Forum of Human Rights Defenders, held Sept. 26-28 in Panama, participants called on the region’s governments to strengthen protection and ensure a safe and enabling environment for environmental protectors, particularly women.

While the Mexican women defenders who gathered in Mexico City valued the Escazú Agreement, they also stressed the importance of its dissemination and, even more so, its proper implementation.

Activists Pacheco and Lopez agreed on the need for national outreach, especially to stakeholders.

“We need more information to get out, a lot of work needs to be done, more people need to know about it,” said Pacheco.

The parties to the treaty are currently discussing a draft action plan that would cover 2024 to 2030.

The document calls for the generation of greater knowledge, awareness and dissemination of information on the situation, rights and role of individuals, groups and organizations that defend human rights in environmental matters, as well as on the existing instruments and mechanisms for prevention, protection and response.

It also seeks recognition of the work and contribution of individuals, groups and organizations that defend human rights, capacity building, support for national implementation and cooperation, as well as a follow-up and review scheme for the regional plan.

García the attorney said the regional treaty is just one more tool, however important it may be.

“We are in the phase of seeing how the Escazú Agreement will be applied. The most important thing is effective implementation. It is something new and it will not be ready overnight,” she said.

As it gains strength, the women defenders talk about how the treaty can help them in their work. “If they attack me, what do I do? Pull out the agreement and show it to them so they know they must respect me?” one of the women who are part of the Voices of Life campaign asked her fellow activists.